A Home Worth Guarding

Watchful Roscoe, Roger Scruton, and The Fluttering Primatial Hand of Esztergom

That’s my little old dog Roscoe, guarding the castle against the threat of barbarian squirrels. He’s winding down his life, poor fellow. He’s 13 years old, and according to the schnoodle actuarial charts, doesn’t have much time left. He’s slowing down a lot, and his back left hip is in so much pain that if not for doggie ibuprofen, he would scarcely be able to walk. He’s been lolling around the house, on his dog bed (he’s too weak to jump up on the couch anymore), sleeping a lot. The vet says this is normal for a dog towards the end of his life. Alas.

But today, my son Lucas left the back gate open when he came home, and Roscoe escaped. My daughter Nora found him down the street when she went out for a walk. He was his lively self again. He was so enthusiastic about being outside the house and the fenced-in backyard that Nora decided to put him on a leash and take him for a walk. When she came home, Roscoe skittered around the living room with his customary friskiness, which we haven’t seen in a while. Nora said he was so excited about being out that he actually ran for part of the walk, despite his bad hip. Could it be that the old dog was actually depressed, and just needed a change of scenery?

I’m thinking about the lesson in that as I sit here at fireside with Roscoe at my feet. I’ve been so run-down and mopey, bound as I’ve been to the house. I never go outside to walk, and don’t leave the house to do much. It feels so — I dunno, I’m bored and gloomy here, but I can’t work up the wherewithal to step outside of the dull routine I’ve established of laying around waiting for the Covid crisis to pass. Nobody is forcing me to stay in the house; I just do it. Roscoe surprised me by how different he was when he came back from his spin around the block. Maybe tomorrow I’ll take him out. It would do me some good.

I had not realized until travel was taken away from me (and from all of us) this year how much I had depended on it to draw me outside of myself. I do not enjoy the hassle of flying, especially having to sleep on a plane, but it never fails that travel — especially overseas travel — restores in me a zest for life, even though by the end of my trips, I’m ready to be home. Why is that? Of course there’s the pleasure of discovering new places and things, as well as meeting new and interesting people, and learning about how they live. But for me, there’s something more.

I did not have the conceptual vocabulary to explain it to myself when I was younger, but being an Orthodox Christian has helped. Orthodoxy regards the material world iconographically. That is, it construes the world as a window through which God reveals himself. Medieval Catholicism had a similar view. In my book The Benedict Option, I write:

The medieval conception of reality is an old idea, one that predates Christianity. In his final book The Discarded Image, C. S. Lewis, who was a professional medievalist, explained that Plato believed that two things could relate to each other only through a third thing. In what Lewis called the medieval “Model,” everything that existed was related to every other thing that existed, through their relationship to God. Our relationship to the world is mediated through God, and our relationship to God is mediated through the world.

Humankind dwelled not in a cold, meaningless universe but in a cosmos, in which everything had meaning because it participated in the life of the Creator. Says Lewis, “Every particular fact and story became more interesting and more pleasurable if, by being properly fitted in, it carried one’s mind back to the Model as a whole.”

For the medievals, says Lewis, regarding the cosmos was like “looking at a great building”—perhaps like the Chartres cathedral—“overwhelming in its greatness but satisfying in its harmony.”

The medieval model held all of Creation to be bound in a complex unity that encompassed all of time and space.

I knew none of this until well into adulthood, but from an early age, I intuitively approached the world as if it held secrets to be discovered. A high school teacher once likened me to the Elephant’s Child of Kipling’s short story, “full of ’satiable curtiosity.” Whenever I visit a new city or country, I always try to approach it with an open mind and an open heart. I want to know what life is like for the people who live there, and what I have to learn from them. This does not come from a cultivated goo-goo open-mindedness. I instinctively love mystery and variety. The worst thing about the modern world is how it tends to flatten and homogenize all things.

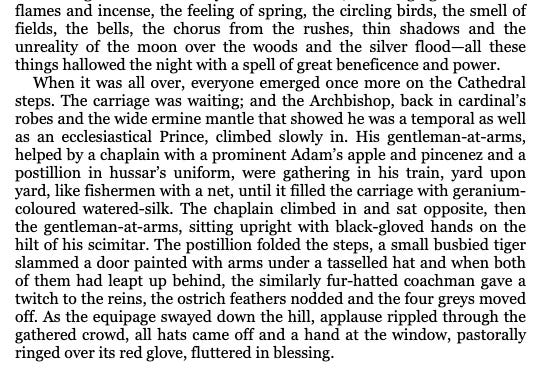

My ideal traveler is the late Patrick Leigh Fermor, an Englishman who, in 1934, at the age of 19, set out to walk from the port of Hoek van Holland all the way to Constantinople. His great trilogy — the third part of which was unfinished at the time of his death in 2011 — begins with A Time of Gifts, then picks up in Between the Woods And The Water, which begins with Paddy’s arrival on Holy Saturday in Esztergom, on the Hungarian side of the Danube. Rather than copy this passage from my paperback version, I was able to photograph it from the Kindle version. This is travel writing at its finest:

Can you even? Paddy’s writing is too rich for some folks, but I think he gives the world its due. My world this year has been too small. When the plague passes, you had better be sure that I’m going to travel as often as I can manage, and am not going to feel the least bit guilty about it. I’m lined up to take a fellowship in Budapest in the spring, and am probably going to go no matter what the Covid situation is, because damn these four walls. If I have to risk my life to catch a glimpse of the Prince Primate, Archbishop of Esztergom, flutter his red-gloved hand in blessing on Easter, well, fine. I’ll be like Roscoe gallivanting around the block on his bad schnoodly leg, not even caring.

Or not. A food writer for The Washington Post describes coming down with Covid:

On Wednesday night, just 24 hours into this nightmare, I woke up around 4 a.m., feeling generally uncomfortable. I sat up in bed, and within a matter of minutes, I could feel my body start to turn against me. I felt warm, so I slid to the floor to let the hardwoods cool my skin. That’s when I experienced a pain so profound and all-encompassing I couldn’t put it into words for my wife, Carrie. All I could do is cry, “Oh God,” over and over again. I knew I wouldn’t be able to stand the pain for long. I also knew I couldn’t move from the floor.

Then the nausea hit me. It felt like something dark and sticky were trying to exit my body, and I couldn’t move myself to the bathroom. Carrie instead brought me a bowl, and I began imagining that this is where it would end: curled up on the floor, in my “Exile on Main Street” T-shirt, head slightly perched above a stainless steel mixing bowl, crying out to a god I never understood. And then, just like that, as if by divine intervention, the pain and nausea disappeared.

Of my friends who have had Covid, none has experienced it in exactly the same way. The weirdest was a very fit young physician who spent the first day in a barely-contained rage, and the second day with satyriasis.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the meaning of suffering these past couple of years, primarily because that emerged as the most important theme in my Live Not By Lies book: developing the ability to bear suffering without breaking as a key to survival. I turned in the final version of the book just as Covid was getting started. During this year I have turned often to the stories I read, and heard firsthand, from people who endured suffering under communist totalitarianism — this, to right my own ship. “It can always be worse,” and variations on the theme of shaming oneself out of self-pity, only work for so long. At some point, you have to dig deeper to mine meaning out of the experience.

I’m finding that the enforced isolation of Covid makes it so difficult to endure. Even though living through a kind of house arrest is pretty cush as endurance trials go, you realize how much easier other, more acute trials were to live through, because you were able to do it with others.

The most terrible and the most beautiful days of my life were the autumn and early winter of 2001, living in New York City. I hardly need to explain why those days were so terrible, but the beauty? You kind of had to have been there. I wrote a little something back then about going to a place near Ground Zero on a snowy night with my wife and little boy, to hear the Roches sing Christmas carols. That was an unusual occurrence, though. Most of the days were sad — so many funerals — and anxious, with all of us afraid that It Might Happen Again. They flew airliners into the Twin Towers. If that can happen, what else might they do?

And yet, life had such an intense sweetness to it. People — New Yorkers at that! — were so kind to each other. It felt effortless. It was like we came to ourselves, in the eye of a hurricane, and realized who we were, and what we meant to each other. That had never happened to me before or since. We all knew it was going to go away, and it was of course bought at far too high a price. But there it was. What a thing to admire the goodness of others, everywhere, and to feel it not as sentimentality, but the way the world really is.

Every four days in the US, we lose as many people to Covid as died on 9/11. Most of us are waiting this out alone, or almost alone. If 9/11 taught us the meaning of sacrifice and solidarity, what is Covid teaching us? The skill of abiding?

Marx denigrated religion as “the opium of the people,” but the insult is more insightful in its original context. Marx wrote:

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions.

Marx wasn’t entirely wrong about that — and I say that as a religious believer. Few can withstand intense and prolonged suffering without hope. Marx thought religion anesthetized the poor, and made them unwilling to change their miserable conditions through revolution. Elsewhere, Marx famously said that the philosophers have heretofore thought their task was to understand the world, when the point is actually to change it. But what if you can’t change the world, or can’t change it fast enough? What if the limits of our existence in time compel us to suffer? There is nothing any of us can do to force scientists to work harder than they are doing now to develop a vaccine. How do we endure the wait, and the suffering and dying amid the waiting, without losing our hearts and our minds?

What if religion — at least the Christian religion, which sanctifies suffering and gives it transcendent meaning — is not only the opium of the people, in that it makes pain bearable, but in keeping hope alive, is also the penicillin?

I dunno, that’s all I have tonight. Last night I needed something escapist to lift the spirits. I watched the Downton Abbey movie. It was like eating a scone piled high with jam and clotted cream for supper — not satisfying or memorable, but pleasurable and kind of silly. There is a lot to be said for immersing oneself in the sudsy travails of English country aristocrats. Spending a couple of hours in a dingy Ken Loach eat-your-boiled-veg drama set in a housing estate is not my idea of escape.

Lo, if I do make it to Budapest in the springtime, I will visit one of the Roger Scruton coffeeshops in the city. The first one has just opened, with more to follow. John O’Sullivan writes:

Roger’s widow, Sophie, has given it some memorabilia of his life — books, records, an old-fashioned gramophone, his favorite brands of tea, his teapot, etc. — and it’s intended to be a place of intellectual and social conversation as well as of light eating and civilized drinking. Roger’s books will be on sale — he wrote more than 40 on topics ranging all the way from sex and wine to left-wing thinkers. So will opinion journals and magazines — principally conservative ones, of which Central Europe now has a good number such as the European Conservative, which Alvaro Mario Fantini edits from Vienna — with pride of place going to the Salisbury Review that Roger founded and edited for many years and that still flourishes modestly with regular contributors like the coolly formidable wit Theodore Dalrymple. There’s a space in the café for the occasional philosophical debate, poetry reading, or book launch, and its basement doubles as a television and internet studio that hosted its first event this month — see below.

All this is traditional in coffee houses going back to 18th-century London and indeed to Central Europe, especially from about 1860 to 1940. But the special appeal of the very English Sir Roger to Central Europeans is interesting and significant. It rests on three features of the man and his life.

The first one, not to be underestimated in an intellectually snobbish part of the world, is that Roger was a first-class professional philosopher who knew his Kant and Hegel, his Descartes and Pascal, his Burke and Hume, his Sartre and Aron, as well as or better than any Doctor-Doctor. He led an extraordinarily varied and active life — fox-hunting, composing an opera, founding a publishing house, writing a weekly column for the London Times — and both drew and commented upon all these activities in his philosophical work. His life and work added depth to each other in both directions.

Second, Roger was an intellectual Scarlet Pimpernel saving minds rather than lives in the Central Europe of the final decades of communism. He organized Western writers and academics to smuggle books and themselves into Poland, Hungary, Romania, and Czechoslovakia, where they delivered private lectures on the latest developments in their specialties, read poetry, exchanged ideas, and formed what were in effect underground universities with both lecture halls and senior common rooms in people’s homes. The atmosphere of those times is well-caught by two plays by Tom Stoppard, who was a friend of Roger’s: his play for television, Professional Foul, which is available on the Internet, and Dogg’s Hamlet and Cahoot’s Macbeth, in which absurdism comes to the rescue of truth when a secret policeman invades a private performance of Shakespeare. Roger’s missions were a serious and risky venture requiring courage and commitment to truth, with no hope of any reward other than doing the right thing. He and his collaborators were tracked, roughed up, threatened, and expelled. But some of their students went directly from jail to ministerial office after the velvet revolutions, and others went on to university chairs, editorial desks, and diplomatic postings (though few, I think, to corporate boardrooms).

Third — and not solely because of his dissident activities 30 years ago — Roger had a large following of conservative students and intellectuals throughout the region.

Read it all. Of course they love Roger Scruton in the former Communist countries, because, as John O’Sullivan writes, he took risks to help them when they were held captive. The Czech authorities once arrested Roger for his work helping underground intellectuals in Prague. He led an initiative, one joined by left-wing academics like Charles Taylor and Jacques Derrida, to establish a secret, degree-granting university there. In 1998, Vaclav Havel, the playwright, dissident, and first president of a free Czechoslovakia, awarded Roger a medal for his service to the cause of liberty and free thought.

Here is a link to the Scruton coffeeshop Facebook page.

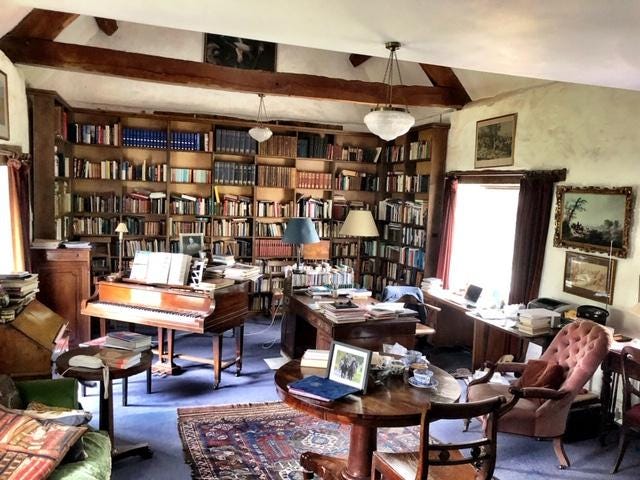

In the summer of 2019 — just before Roger learned he had cancer — my friend Laura Croft and I visited the great man at home in Wiltshire:

Here is what his study looked like in the farmhouse:

That is heaven, in my view. What you can’t see is that a door opening onto the garden was open, letting in the coolness of an English summer. If I had to be housebound during a pandemic, then please, Lord, let it be in Sir Roger’s study. In photos I saw on its Facebook page, the Scruton coffeeshop in Budapest appears to have a Swedish modern aesthetic. It is still young; in time, as it grows in Scruton-ness, it will look something like this. Perhaps the Cardinal Primate of Esztergom could pay it a visit and flutter his red-gloved hand in consecration, and turn IKEA into Scrutopia.