Aaron Renn: Our Own Malcolm Gladwell

And: Saunders & Russians; JD Vance, Ugly American?; Anti-Humanism; More

I could not possibly be happier to see Aaron Renn profiled by The New York Times — and by Ruth Graham, who truly is an excellent religion journalist. I’ve used one of my monthly gift articles to unlock it for you all. As you may know, I’ve long been a booster of Aaron’s work, and consider him to be one of the most important Christian public intellectuals in America today.

Aaron, you’ll recall, is the Protestant/Evangelical thinker who came up with the concept of “Negative World” to describe the shift in American culture towards Christians. As the Times characterizes it:

Mr. Renn’s schema is straightforward. Modern American history, he argues, can be divided into three epochs when it comes to the status of Christianity. In “positive world,” between 1964 and 1994, being a Christian in America generally enhanced one’s social status. It was a good thing to be known as a churchgoer, and “Christian moral norms” were the basic norms of the broader American culture. Then, in “neutral world,” which lasted roughly until 2014 — Mr. Renn acknowledges the dates are imprecise — Christianity no longer had a privileged status, but it was seen as one of many valid options in a pluralist public square.

About a decade ago, around the time that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges made same-sex marriage legal nationwide, Mr. Renn says the United States became “negative world." Being a Christian, especially in high-status domains, is a social negative, he argues, and holding to traditional Christian moral views, particularly related to sex and gender, is seen as “a threat to the public good and new public moral order.”

… It’s just one instance of what Mr. Renn depicts as a pattern: Christians who hold traditional beliefs about a range of social and political issues have come to be treated as pariahs by secular elites even if they have made an effort to avoid gratuitous offense. The phenomenon goes beyond “cancel culture” to describe a kind of wholesale skepticism of many Christian beliefs and behaviors in domains like academia and the corporate world.

Most of us socially conservative Christians have experienced this, or at the very least know someone who has. Relatedly, WaPo columnist (and libertarian) pal o’ mine Megan McArdle tweeted yesterday:

What I especially liked about the Ruth Graham piece is how she took a broad view of Aaron’s development as a thinker — especially how his recovery from a painful divorce led him, chiefly a thinker to that point about urban issues, to start thinking more critically about religious life in America:

In the wake of his divorce, Mr. Renn said, he was in a low moment professionally and personally. He credits his recovery in part to the “manosphere,” the sprawling network of masculinity influencers that he identified as a serious cultural phenomenon long before it burst onto the national political scene. From a podcast hosted by the right-wing social-media personality Mike Cernovich, he learned about strength training, and began feeling better about his body. From another influencer, he honed his eye contact, a skill he said he was still “maybe not the best at.” He said this just as I was thinking to myself that it was so intense I wasn’t sure how or when to look away.

As an evangelical, Mr. Renn began wondering why contemporary American churches had so little to say about so many fundamental realities he was encountering. Online dating was a marketplace, and it turned out that nice Christian women wanted more than a nice Christian guy, contrary to the shallow dating advice of megachurch pastors. Evangelical churches lamented divorce even as they criticized the same forms of traditional masculinity that the manosphere was instructing him to hone, in order to improve his marriage prospects.

“These guys have cracked the code on reaching young men, and they’re actually giving a lot of practical advice,” Mr. Renn said. “And by the way, some of the things that the church is telling these guys is just wrong.”

(He has been happily remarried for some years now, and has a son with his second wife.)

Aaron was an early proponent of my own Benedict Option idea, which he saw his Evangelical tribe unwisely rejecting. He and I have talked about this over the years; his view is that American Evangelicals in part could not accept that they are now an increasingly despised minority in American life. I believe that it took a conservative Evangelical like Aaron to convince them that the Orthodox Rod Dreher was right:

On the Christian right, then, a thesis is emerging: If conservative Christians are no longer a “moral majority” but a moral minority, they must shift tactics. They ought to be less concerned with persuading the rest of the country they are relevant and can fit perfectly well in secular spaces. They don’t. Instead, they must consider abandoning mainstream institutions like public schools and build their own alternatives. They must pursue ownership of businesses and real estate. And they must stop triangulating away from difficult teachings on matters like sexuality and gender differences. Resilience over relevance.

“Like the Hebrews crossing the Jordan after 40 years in the desert, evangelicals have entered unfamiliar territory,” Mr. Renn writes in his book, issued by a major evangelical publisher in 2024. “Finding a path in this fundamentally unknown world will require a different approach from the strategies of the past.”

The book is Life In The Negative World. It came out just over a year ago from Zondervan, which is my new publisher, and also the publisher of Catholic Ross Douthat’s latest. Traditionally a major Evangelical publisher, Zondervan seems to be making a move to speak more broadly to American Christians. Good. We small-o orthodox Christians need to reach across confessional lines to each other.

If you don’t subscribe to the Aaron Renn Substack already, please do. Aaron gets zero support from any church institution or other institution. He’s entirely reader-supported, which grants him a certain independence of thought.

George Saunders & The Russians

Here is a link to a PDF of a rather short short story, “In The Cart,” by Anton Chekhov. [NOTE: “The Schoolmistress” is the alternative title for the same story. — RD] You can read it in just a few minutes. It is a gem. It’s the story of a short journey in a horse-drawn wagon made by a lonely schoolteacher in a Russian village. But it seems that all of life is in that story. Yesterday, after I finished it, I reached out to a good friend with whom I had had a misunderstanding recently, and wrote a long letter, reconsidering our situation in light of what I had learned from that simple story. Chekhov helped me see our relationship in a new light.

I found my way to the Chekhov story via a wonderful, acclaimed book someone put me onto, A Swim In A Pond In The Rain, by the short story master George Saunders. Saunders teaches writing at Syracuse University, including a class on Russian short stories. In this terrific little book (so far — I’m only partly into it), Saunders takes apart stories by Chekhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, and Gogol, not just to show how fiction works, but also to learn the life lessons these authors have to teach us. In the introduction, Saunders writes:

“We’re going to enter seven fastidiously constructed scale models of the world, made for a specific purpose that our time maybe doesn’t fully endorse but that these writers accepted implicitly as the aim of art—namely, to ask the big questions, questions like, How are we supposed to be living down here? What were we put here to accomplish? What should we value? What is truth, anyway, and how might we recognize it?”

This little book is totally disarming. As a writer and a reader, I’m learning a lot from it — Saunders is conversational in his style, and highly engaging — but also learning some things about, well, life. Like I said, I put down the Chekhov story and Saunders’s meticulous teaching about it, and wrote a letter to my friend.

The NYT podcast host Ezra Klein had Saunders on in 2021 talking about the book. Excerpt:

EZRA KLEIN: You wrote about that. You gave this example that stuck with me for a reason that would become obvious in a second. Where you wrote, look, say you’re a world class worrier. If that worry energy gets directed at extreme personal hygiene, you’re neurotic. If it gets directed at climate change, you’re an intense visionary activist.

And it reminded me of something that my wife once said to me, that actually, there are very few moments like this. But it completely changed my view of my own nature, and my own history, and the story I told about it. I was a pretty bad hypochondriac when I was younger. And I told her that I was glad she didn’t meet me then, because I was just always worrying. And who’d like that guy?

And she said to me, oh, you haven’t changed at all. You just hadn’t found work yet. And now you just put all that worry and energy there.

GEORGE SAUNDERS: That’s beautiful. Yeah, that’s exactly what I’m —

EZRA KLEIN: And I was totally floored by that. Because it made total sense. It’s the same energy, but now it makes me, by society standards, successful rather than neurotic.

GEORGE SAUNDERS: Yeah.

EZRA KLEIN: But it is a lot of neurotic energy.

GEORGE SAUNDERS: Yeah.

EZRA KLEIN: It’s just being channeled differently.

GEORGE SAUNDERS: What a lovely way for her to see you too. That’s really a gift. Because when you talk about acceptance, that’s really what we’re talking about, is you’re born a certain way. And nobody chooses the packaging with which they’re born. And then the question is, OK, given this, you do have some choice in how you disperse it, I guess.

This touches on the lesson in the story “In The Cart”: nothing much changes, but everything changes, because the protagonist experiences a moment of wonder, of enchantment. Chekhov, by extension, shared that enchantment with me, the reader, which is why it motivated me to write to my friend, reconsidering our friendship from a different, more positive light.

Incidentally, Klein and Saunders talk a lot about politics. Saunders’s politics are not mine, but I appreciate his refusal to hand-wring over Trump, and instead attempt to understand why people would find Trump appealing. He approaches it like a real writer.

The reason I bring any of this up is because that brief Chekhov story is a great example of everyday enchantment. God doesn’t enter into it, mind you, but Chekhov gives us an example of how, in effect, the protagonist sees a comet blazing across the night sky — that is, has the kind of experience that we all do from time to time, but she’s ready to receive it in a new way — and it changes her life. Read it for yourself at the link above, and see what you think.

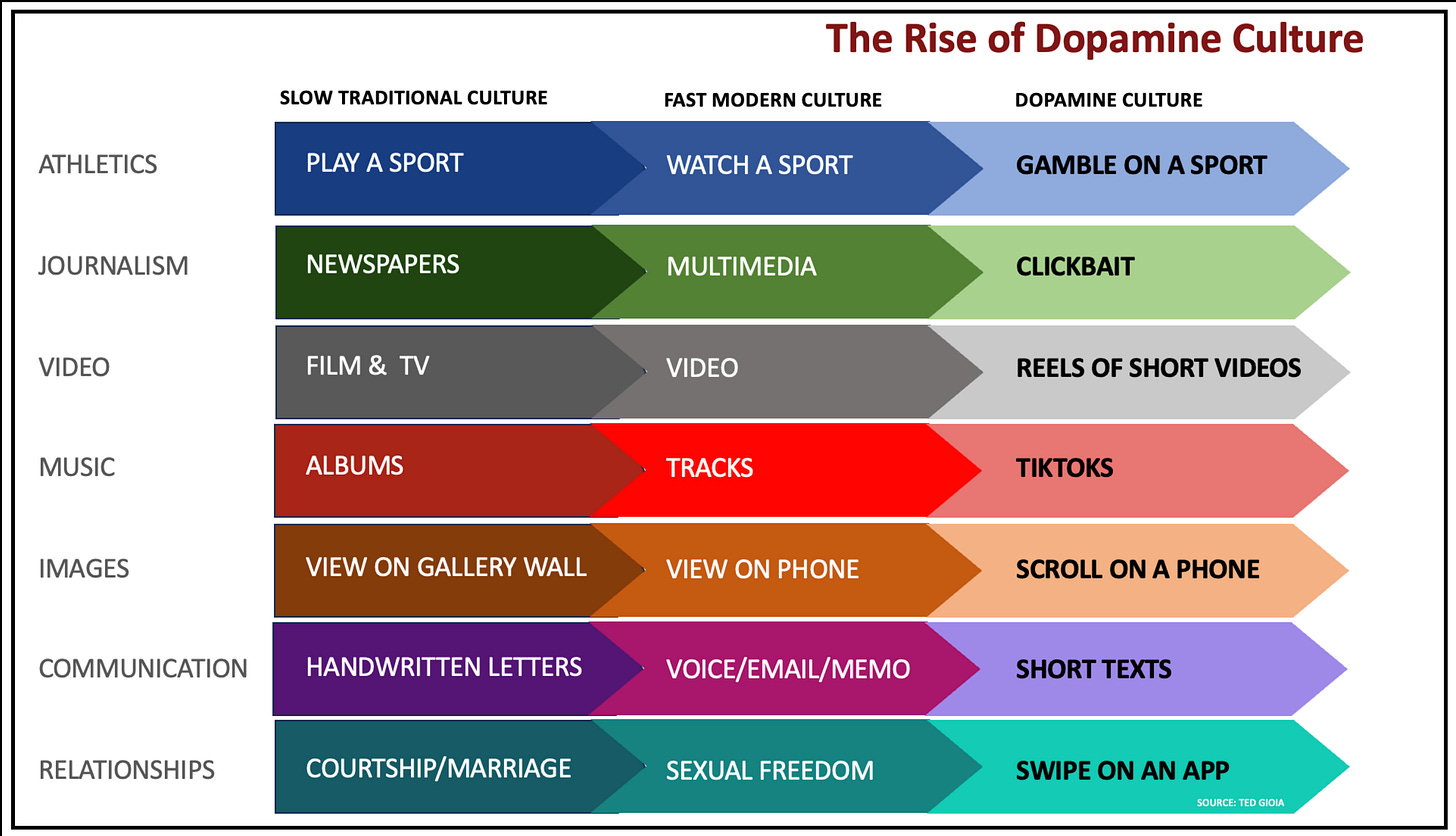

Dopamine Culture

A friend sent this. Seems very sharp to me:

Goodbye, National Park Centers

A subscriber who usually likes my stuff here wrote to share her irritation with how uncritical I have been about Trump’s Hulk-smash approach to government. She shared this new story. Excerpt:

The Trump administration is seeking to cancel the leases for 34 National Park Service buildings, including visitor centers, law enforcement offices and museums that house millions of artifacts.

The General Services Administration has proposed terminating most of the leases within a year, saying the decision could save taxpayers millions of dollars. But park advocates have warned that the move could harm the visitor experience at national parks across the country, especially during the peak summer season. The 34 locations were included in a larger list of hundreds of federal properties the government was looking to give up or sell.

I had not seen this news until she sent it, and I agree that this seems incredibly foolish by Trump. Why go after national parks? They are a public good that all of us can share. Sure, cancel the stupid DEI initiatives in the parks, but don’t cancel the park centers. I’ve barely ever been to a national park, but I’m very glad they are there for people to use. I feel the same way about things like symphony orchestras and operas.

Europe Wakes Up, Sort Of

Still reeling from the shock of the Trump administration’s volte-face on Ukraine, EU leaders have approved a plan to massively increase defense spending to meet what they believe is a threat from Russia. In a way, I’m glad that they’re finally taking responsibility for their own security seriously, but I have serious doubts about whether or not European voters will be willing to pay higher taxes and endure cuts to welfare state benefits to fund this. We’ll see, I guess. Leftist journalist Glenn Greenwald is also skeptical:

France’s Philippe Lemoine is similarly gimlet-eyed about all this:

He’s right about that. The “Putin apologist” smear is as omnipresent today as the same kind of smear was in 2002 in the US, deployed against anyone who questioned the wisdom of the coming war on Iraq. It’s designed to shut down thought.

As usual, Hungary is the one dissenter from the EU consensus. Italy’s Giorgia Meloni made a bonkers proposal yesterday: that NATO extend Article V protection to Ukraine, despite denying it NATO membership. Article V is the provision in the NATO charter that says an attack on any NATO country is an attack on them all. What she’s saying is that Ukraine should get the benefits of NATO membership — bringing all of NATO into the war with Russia — with none of the responsibilities. I presume this will go exactly nowhere, because if it were to be adopted, that would be the end of NATO, in a stroke. There is no way the US would agree to go to war with Russia on Ukraine’s behalf. And there is absolutely no way a NATO threat means anything absent US participation, given how weak European militaries are.

European chiefs had better get very serious, very fast, about the migration issue, because it’s a huge drain on their budgets, and — this is much more difficult for them to admit — it’s a big internal security problem. It is not at all clear to me how they think they’re going to be able to defend the borders of Ukraine when they cannot or will not defend their own borders.

How insane is it over here? Take a look at this video clip from Ireland. An African migrant is on the street with a microphone trying to guilt the Irish into giving Africans there power and land, in reparation for, get this, Irish complicity in the slave trade. Another African protester sits on the street holding a sign reading, “Justice For George” — Floyd, that is. These African grifters know very well how to manipulate guilt-ridden European progressives. An Irish friend I spoke to at ARC was seething with contempt for his government. He pointed out that they had every reason to know, from widespread European experience, what massive social problems came with taking in Third World migrants — yet they did it anyway, to preen morally.

J.D. Vance, ‘Ugly American’?

Yesterday I appeared on BBC Radio 4’s popular morning news program to defend my friend J.D. Vance. The host sounded bewildered that I could think that wokeness was a serious problem in light of what Putin has done to Ukraine. Not sure about the logical leap there — both can be problems! — except that he can’t see why anybody should care at all about wokeness. A British friend texted after my interview to say that’s the first time in years he has heard a normal human being talk on Radio 4.

In today’s UnHerd, Tom McTague writes about why they all despise Vance. Excerpt:

James David Vance is the epitome of what so many Europeans loathe about America: brash, insular, moralising and imperious. And yet — even more annoyingly — like America itself, he combines this with intelligence, education, wealth and, ultimately, power. Vance is the Hillbilly Crown Prince countering the Old World’s scorn with a contempt of his own. In the unseemly battle between the two over the past few weeks, neither side has emerged with much credit. And yet, the most uncomfortable reality of all for Europe today — and Britain in particular — is that what we see in Vance we also see in our own future.

When Vance asks what America has to gain by risking a war with Russia, Britain, too, will soon begin to ask what is in it for us as part of the proposed peace keeping settlement. When Vance demands that Europe pay more for its own defence, Britain will also want to know why it should shoulder a disproportionate share of the burden for the continent’s defence without recompense. Germany, for all its current economic difficulties, remains far less indebted and much wealthier than Britain. Norway, meanwhile, has spent the past decade growing ever richer as a result of the spike in gas prices. Shouldn’t both of these countries, then, be contributing more in financial terms towards any future British deployment? Finally, when Trump himself complains that Europe is treating the US unfairly while asking for its support, surely it is reasonable to ask why British troops should be sent to defend the EU’s borders when the EU itself refuses to negotiate even the most basic defence “pact” with Britain until it hands over access to its fishing grounds?

At the heart of the Trump-Vance strategy is the pursuit of a new grand bargain in global affairs, in which the US acknowledges the emergence of a new multipolar world governed by great powers rather than international law. While Europe is not — yet — one of those powers, it too faces a moment of reckoning; when the old EU order is no longer enough to govern the continent’s security, new grand bargains will be demanded. It has not gone unnoticed in Downing Street that, today, Europe’s security is increasingly dependent on four countries none of which is a member: Britain, Norway, Turkey and, of course, Ukraine. If America’s position in the world is no longer sustainable, then neither is the current concert of Europe. Whether any of Europe’s current leaders can rise to the challenge and create something new is far less clear, although Emmanuel Macron made an effort to do so.

In an address to the nation last night , the French President argued that “the future of Europe cannot be decided in Washington or Moscow”. He said that while he wanted to believe that “the US will stand by our side”, Europe had to be ready if that wasn’t the case. “We need to be able to recognise the Russian threat and better defend ourselves in order to deter such attacks. We need to provide ourselves with more arms. We need to do more than we have in the past to reinforce our security.”

In a sense, then, Vance, is both a harbinger of our upheaval — and an author of it. As such, he is a curious character to capture. He is not the Appalachian red-neck of general European disdain; he is far too Ivy League and Silicon Valley to be understood as such. But nor is he merely a tough-talking under-boss of the Dick Cheney variety: Vance is something sharper and more elusive; closer to Richard Nixon than most recent holders of the Vice Presidency. He’s a man of power and ambition who is offensive to European sensibilities not just because of the dishonesty of his casual asides, but the fragility they reveal about our own predicament.

There you have it: Vance makes Britons and Europeans get serious about themselves and their own illusions, and they hate him for it. McTague, on his fellow Brits:

The paradox of JD Vance is that his insults only matter because we are too weak for them not to — yet if we choose to become strong, we will begin to sound more like him. We are dependent and so we are craven.

McTague points out that British troops were actually defeated both in Iraq and Afghanistan, but Britons are loath to admit it. Vance forces them to. It’s worth pointing out that Vance (and Trump) are forcing Americans to face up to our military defeats in both places as well. This is why they are driving US foreign policy away from the global policeman model, which failed the test.

Anti-Humanism In Our Time

This morning I’m finishing answering questions for a written interview for a French outlet. My questioner asked me about Elon Musk, libertarianism, and the Trump moment. In the response I wrote last night, I expressed fear that the standard American habit of blindly accepting technology that gives us what we want, and coming up with moral justifications for it later, is going to be the ruin of us when it comes to AI and transhumanism. I pointed out the experience I had in 2018 of listening to the young French Catholic right-wing politician Marion Maréchal giving a fantastic speech to CPAC (see above), in which she made a holistic, very Catholic argument for the defense of the human person, including in the face of these dehumanizing technologies. I remember thinking at the time that there’s probably not five people in that crowd who have the slightest idea what she’s talking about.

Comes the great Carl Trueman today to make the same point in First Things. Excerpt:

America has (thankfully) yet to reach the depths of Canada’s culture of assisted suicide. But the lack of a coherent anthropology already shapes medical policy. President Trump’s actions on transgenderism in sports and the military are a welcome move toward sanity. But his actions on IVF reveal that he is not guided by a coherent understanding of what it means to be human. As with Canada’s euthanasia laws, taste and not anthropology rules the day. Elon Musk’s family experience has left him rightly disgusted by those who press transgender treatments on the vulnerable. But the tech-libertarianism that drives so much of the Silicon Valley imagination loves IVF and associated technologies. The difference derives from matters of contemporary cultural preference. This can only lead to chaos in the long run, however grateful we should be for the policies addressing the transgender issue. If I were a betting man, I would put money on the emerging tech bros deciding what it means to be human for the rest of us. That is not a hopeful scenario, and it will have social and cultural consequences. Medical ethics—from issues of life to issues of death—needs a stable anthropology as its foundation. Neither Canada, nor the U.S.—nor any other Western country, for that matter—seems to be able to articulate one at this moment in time.

Ours is an age marked by anti-humanism. By that I mean that we live at a time when the very nature of what it means to be human is not simply something upon which there is currently no consensus. …

I leave in a couple of hours on a train for Bratislava, to appear on a panel discussion at a conference. Our panel will talk about culture war. The host signaled that he will be asking panelists about particular aspects of the culture war, including asking us to identify where there have been winners and losers. I plan to point out that on race and ethnicity, conservatives might — might — be turning this around after the defeats of the past decade, and we might finally have stopped the advance of the Sexual Revolution at the transgender front (but that is not remotely the same thing as victory).

But on the whole, the fact that there is no consensus on what it means to be human means that whatever battles we might win, social conservatives will be fighting a losing war. The fact that there is no real battle to be had over IVF gives the game away. The US has a strong pro-life movement, which in principle ought to be opposing IVF. For one, if you believe that life begins at conception, then the fact that “surplus embryos” must be created for IVF to succeed means de facto abortion. This is something that many Christians and other pro-lifers do not want to face.

Second, the fact that we have come to regard human life as a commodity that can be manufactured in a lab, and the carrying of that life to term something that can be outsourced to a surrogate who agrees to gestate the child, means that we have already conceded that human life is a consumer product.

But you know how people are — including many of “our people” (conservatives): they look at the outcome — a beautiful baby in the arms of a loving parent, or parents — and think that the result justifies crossing whatever bright red moral lines necessary. This is how we Americans think. It is not going to end well, no matter who is in charge in the White House.

Good weekend, y’all!

I'm immediately suspicious of 'the national parks are being closed!' stories. Remember, this is the Democrats' tactic whenever there's a budget battle as well. The most camera-friendly, unobjectionable, wholesome face of government is self-slapped to elicit sympathy and undermine principled reform.

The article mentions that 34 *buildings* (not 34 national parks themselves) are being sold or not re-leased. There are (quick search) 63 national parks, and 429 'national park sites' (e.g. national battlefields, national seashores, etc.) in the USA, most of which surely comprise many buildings, so this is hardly a comprehensive shutdown.

And if you read the article carefully, several of the examples cited are buildings in urban areas that host visitor centers that have information about a national park, but aren't actually in a park per se.

The government rents a lot of office buildings from private sector leasing firms. It’s these leases that the Trump Administration is going after, not the inherent government functions currently occurring in those spaces.

This is how the Democrats lie. By scaring people into thinking that Yellowstone is being shut down permanently.

Believe nothing from these people. Nothing.