Defending Divorced David Brooks

And: The Miseries Of Heteropessimism; The Joys Of Norwegian Sweaters

This is not a pleasant thing to write, and for all I know, the people I’m defending would not want me to write it. But because I care about them, and because I have both some LIMITED insider knowledge of the situation, and a hell of a lot of direct knowledge of how things like this play out in the vicious area that we call the public square, my conscience feels burdened to say something.

You all know that I’m friends with David Brooks and his wife Anne. We used to be closer, in the sense that we were in closer touch, but after 2016, we drifted. It wasn’t on purpose; it’s just that the Trump phenomenon, to which they were and have been both adamantly opposed, and to which I became reluctantly affirmative, seemed to push us apart. I say “seemed,” because I don’t know. Never had any arguments or anything, just drifted. We rarely ever are in contact.

But I still love them and respect them, even though we disagree about some big things (and as you readers know, when I disagree with David on something that I think is important, I say so here). We had a great breakfast together a year ago in London, and argued, in a friendly, normal way, about politics and culture. Again, we disagree on some significant issues, but we are friends, still. This is how it should be. If anybody should choose to refuse my friendship based on politics, that’s on them; that’s not how I roll, and I don’t think that’s how the Brookses roll either.

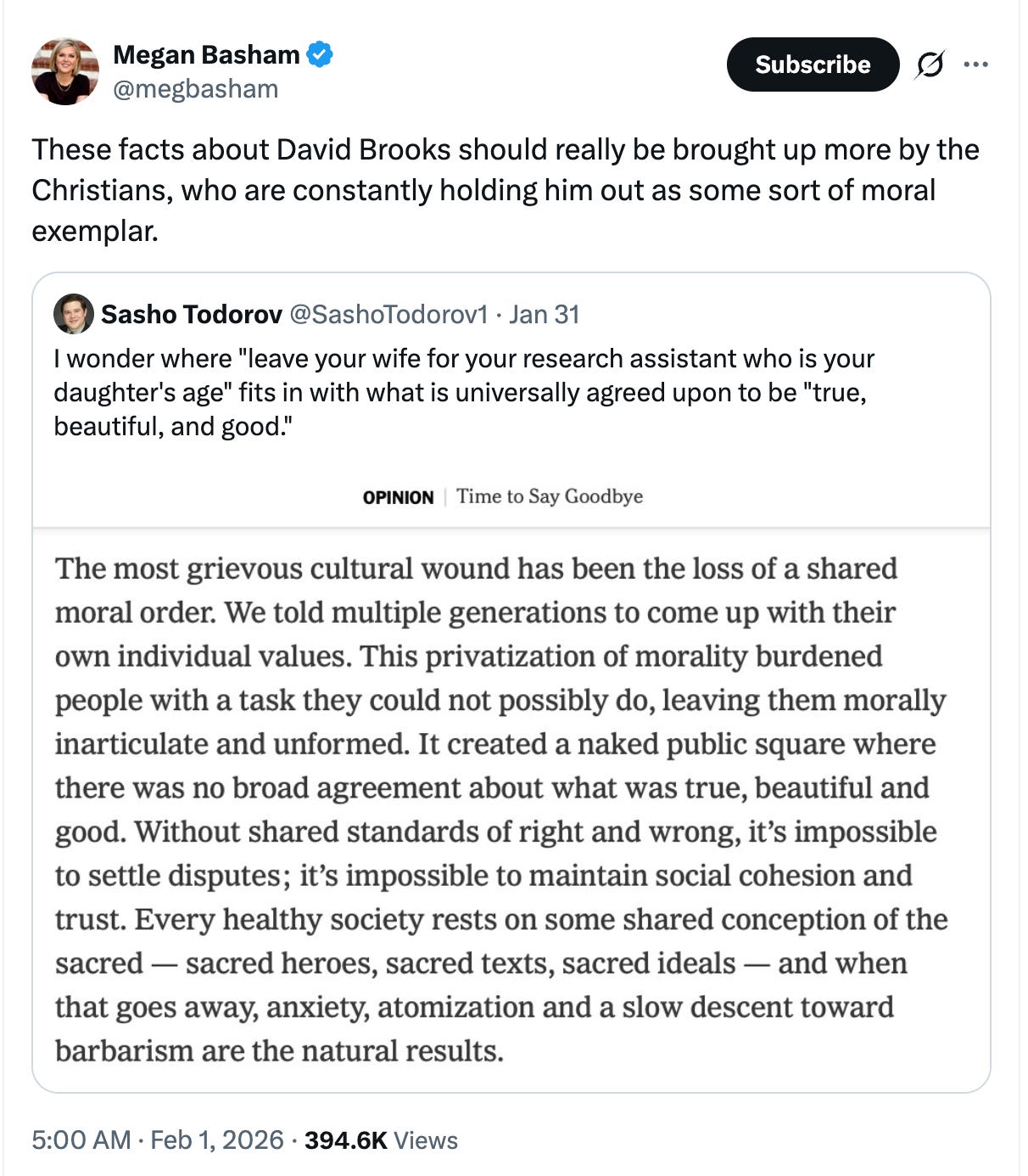

I give you that background so you’ll know where I’m coming from personally with all this. Over the weekend on X, Megan Basham — a pundit I don’t know personally, but whom I like and respect, have been friendly with, and consider to be a sister in Christ — came after David like this:

That triggered me. As I said, I disagree with David about some big things — race and LGBT, for example, on which he takes a more liberal line — but he’s unquestionably right about the loss of the “shared moral order.” How can any conservative disagree? But they went after him ad hominem. It’s cheap and ugly. Hannah Arendt was sleeping with her professor, Martin Heidegger, while he was married. Does that discredit everything she says about moral order? Some pretty prominent Christian intellectuals behaved, or do behave, with a shocking lack of charity, Christian or otherwise, towards people they consider unworthy of them. Brilliant men, all! Are we therefore to discount everything they say about morality and faith? That’s an absurd standard, and makes me think that this weekend contretemps is about people who just don’t like David Brooks, and are throwing what they can at him to tear him down.

Why does this get to me personally? Because as I said on X, I have some expertise here. I know David and Anne, and a lot more about the facts surrounding David, his divorce, and remarriage, than nearly everybody else does. It is a lie and a slander to say what Todorov did — a lie and a slander that has been widely repeated. The thing is, David can’t, or won’t, defend himself, because as he has said publicly, he and his ex-wife agreed at the time of their divorce never to disparage each other publicly. I find that honorable on both of their parts. So he and Anne have to bear the pain of false witness against them. I can’t fully defend them, because if they choose not to make the details of all this public, then I have no right to say here what I know to be true.

This is personal to me. As you know, I too am divorced. My wife filed in 2022 while I was out of the country. We had never talked about it, but it didn’t come as a surprise, exactly, because our marriage had been a disaster for the previous decade. I moved to Europe some months later with my older son Matt; my two younger kids, now both adults, stayed behind with their mother. I had been very close to all my children, and they to each other, so you should figure that something terrible must have happened to precipitate this kind of move. I’ve never talked about it, and won’t talk about it, because to put our family’s business in the street like that would be dishonorable and hurtful, most of all to the kids, who did not choose this.

But over the years, I have had to take lots of abuse in public from people who don’t know the real story. I could easily defend myself from the criticism, but to do so would only compound the tragedy and make things even worse for my kids. And in truth, however the fault in this divorce and what led up to it falls, neither my ex-wife nor I would have wanted this. In a sense, our marriage fell victim to events beyond our control. If that sounds crazy to you, it doesn’t to the friends of mine — including some readers of this newsletter — who know me personally. Life is hard, and can be deeply tragic. I pray every day and every night for my ex-wife, because I know she suffers too. And I just have to suck it up when people slander me over all this.

I’m not saying David’s situation was exactly like mine — it wasn’t — but I am saying that the ten-year, extremely painful breakup of my marriage taught me to be careful about judging divorced people. Few if anybody knew how much my wife and I were suffering inside that marriage, for a decade, before she called it quits. I didn’t resist. It really was time to stop the emotional and psychological hemorrhaging. People didn’t know how bad it was because we put on a good front, mostly to protect the kids.

I don’t know David’s ex-wife, so I don’t know her side of the story. The point I want to make here is that NOBODY outside of a failed marriage really knows what happened within it to lead to the break-up. Nobody. Last night, texting with a Catholic priest friend who told me that if it hadn’t been for what he hears in the confessional, he really wouldn’t be able to comprehend that. He added, “What I learned is that you have absolutely no idea about what goes on behind closed doors, of even the people closest to you.”

In the same way, I have learned so very much about how much people suffer in marriage, since my divorce. Again, I’ve never talked publicly about the details that led to my divorce, but I get a fair bit of correspondence from conservative Christian men (and a few women) who are either divorced unhappily, or suffering in bad marriages. They need help, even if it’s only a sympathetic ear. My God in heaven, the pain people carry, all the while doing their best to keep going — either within a terrible marriage (because they want to protect their kids from divorce, or believe they don’t have the right to divorce, for religious reasons) — or left emotionally high and dry in a divorce.

Just this past weekend in Norway, I met a Christian man who told me a tragic story about how his parents’ divorce affected his family, the details of which are pretty much exactly like what happened to me and my family. It’s horrible stuff. I find myself sitting here in Budapest this morning wondering about that man and his family, and wondering if anybody else who knows them in Norway know what really happened, and the intense, perhaps unresolvable, pain it caused and continues to cause.

David Brooks is a sinner, as am I, as are you, and he hasn’t claimed otherwise. I’m not asking you to give David a total pass here. I’m simply telling you all to withhold judgment, because unless you are a friend, you don’t know his side of the story (and he hasn’t claimed otherwise never disparaged his ex wife even privately to me). Some failed marriages do have clear villains. This is not one of them.

Life is very hard. If you are in a good and steady marriage, thank God for it, and thank your spouse every day. This blessing is not given to everybody.

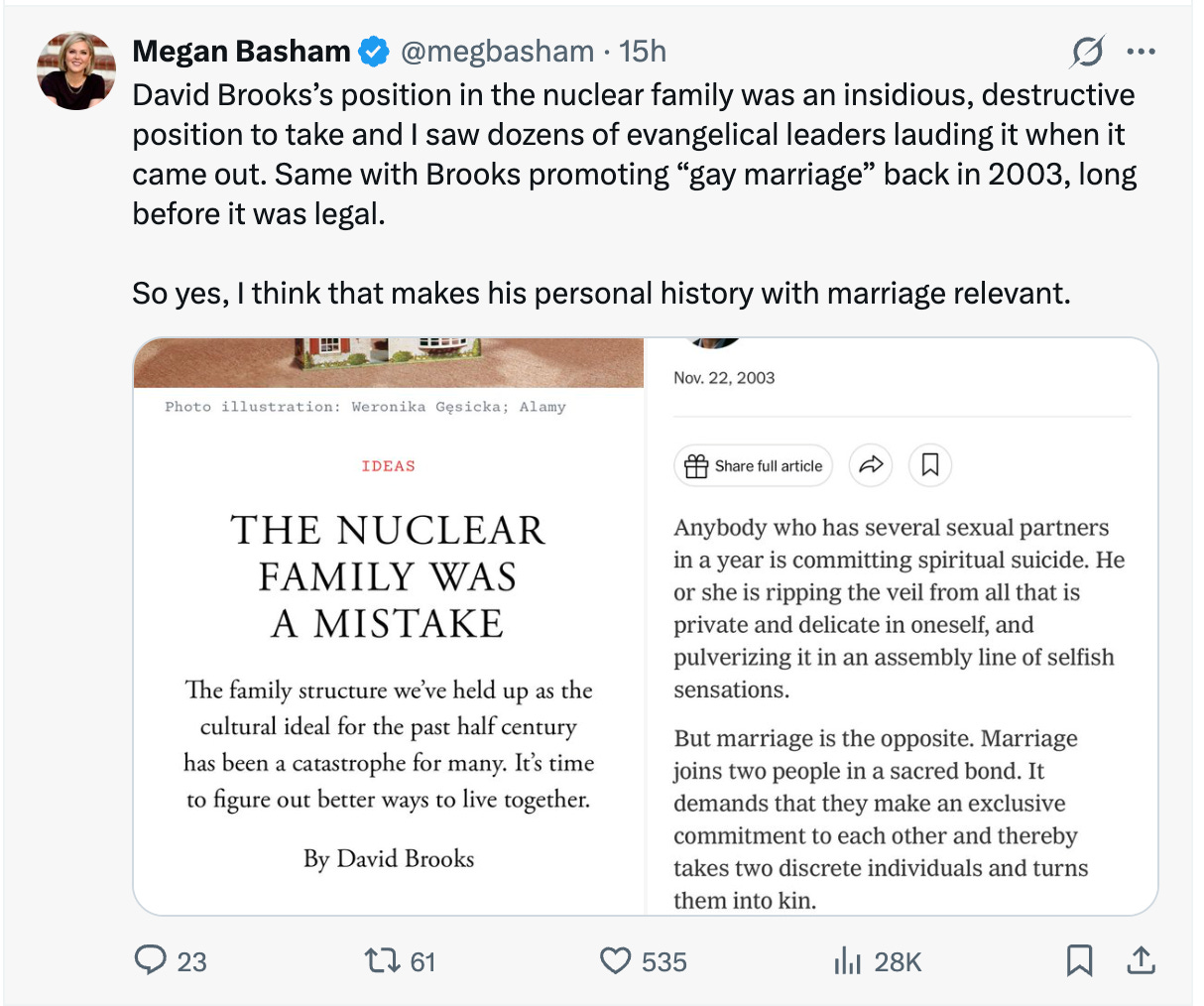

Megan came back on X with this:

Hang on! Here is a link to that essay. Brooks is wrong on gay marriage, and I’ve told him so in friendly personal conversation. But look, in no way does Brooks argue for polyamory or anything like that! He makes a rather conservative argument that the nuclear family is not strong enough to withstand the cross pressures of life without being embedded in a stronger kin network. From the introduction:

This is the story of our times—the story of the family, once a dense cluster of many siblings and extended kin, fragmenting into ever smaller and more fragile forms. The initial result of that fragmentation, the nuclear family, didn’t seem so bad. But then, because the nuclear family is so brittle, the fragmentation continued. In many sectors of society, nuclear families fragmented into single-parent families, single-parent families into chaotic families or no families.

If you want to summarize the changes in family structure over the past century, the truest thing to say is this: We’ve made life freer for individuals and more unstable for families. We’ve made life better for adults but worse for children. We’ve moved from big, interconnected, and extended families, which helped protect the most vulnerable people in society from the shocks of life, to smaller, detached nuclear families (a married couple and their children), which give the most privileged people in society room to maximize their talents and expand their options. The shift from bigger and interconnected extended families to smaller and detached nuclear families ultimately led to a familial system that liberates the rich and ravages the working-class and the poor.

This article is about that process, and the devastation it has wrought—and about how Americans are now groping to build new kinds of family and find better ways to live.

The claims here are undoubtedly true. We’re all living through it. In fact, back in the 1940s, the Harvard sociologist Carle C. Zimmerman, in his great book Family And Civilization, argued from historical examples that the emergence of the “nuclear family” — by which he meant a husband, wife, and children existing atomistically apart from thick kin networks — is the last stage of family before a civilization dissolves. In that book, Zimmerman wrote:

There is little left now within the family or the moral code to hold this family together. Mankind has consumed not only the crop, but the seed for the next planting as well. Whatever may be our Pollyanna inclination, this fact cannot be avoided. Under any assumptions, the implications will be far-reaching for the future not only of the family but of our civilization as well. The question is no longer a moral one; it is social. It is no longer familistic; it is cultural. The very continuation of our culture seems to be inextricably associated with this nihilism in family behavior.

I’ve written a lot about it over the years, and have made the point that the individualization of religion runs parallel to the individualization of family structure. In his Atlantic essay, Brooks observes:

Extended families have two great strengths. The first is resilience. An extended family is one or more families in a supporting web. Your spouse and children come first, but there are also cousins, in-laws, grandparents—a complex web of relationships among, say, seven, 10, or 20 people. If a mother dies, siblings, uncles, aunts, and grandparents are there to step in. If a relationship between a father and a child ruptures, others can fill the breach. Extended families have more people to share the unexpected burdens—when a kid gets sick in the middle of the day or when an adult unexpectedly loses a job.

A detached nuclear family, by contrast, is an intense set of relationships among, say, four people. If one relationship breaks, there are no shock absorbers. In a nuclear family, the end of the marriage means the end of the family as it was previously understood.

Yes, exactly. That is what happened to me. In the essay, Brooks talks about how 20th century life destroyed family stability. It’s not a simplistic story. He writes:

When you put everything together, we’re likely living through the most rapid change in family structure in human history. The causes are economic, cultural, and institutional all at once. People who grow up in a nuclear family tend to have a more individualistic mind-set than people who grow up in a multigenerational extended clan. People with an individualistic mind-set tend to be less willing to sacrifice self for the sake of the family, and the result is more family disruption. People who grow up in disrupted families have more trouble getting the education they need to have prosperous careers. People who don’t have prosperous careers have trouble building stable families, because of financial challenges and other stressors. The children in those families become more isolated and more traumatized.

Many people growing up in this era have no secure base from which to launch themselves and no well-defined pathway to adulthood. For those who have the human capital to explore, fall down, and have their fall cushioned, that means great freedom and opportunity—and for those who lack those resources, it tends to mean great confusion, drift, and pain.

Think about it: how many nuclear families you know live in the same town as their parents, siblings, and cousins? I can think of very few, at least not of my social and professional class. People move for jobs, mostly. This is the new normal. One of my favorite movies is the French film “Summer Hours,” which is about how individualism and globalism wrecked a French family, even as it provided greater opportunities for the individuals within that family system.

Brooks writes that the social and economic conditions that made the nuclear family, as idealized by Americans, disappeared long ago, and they aren’t coming back. But we can’t just sit back and do nothing. He ends the essay by talking about new ways people are trying to create the kind of networks that used to be natural in kinship. You may or may not like his proposals, but to say that he in any sense celebrates the demise of the nuclear family is false. Profoundly untrue. My guess is that a couple of paragraphs in which Brooks cites gays and lesbians rejected by their own families forming family-like networks of their own is what triggered Megan. But that’s one example of many. Most of them are more traditional, or at least not in conflict with Christian tradition.

Brooks doesn’t bring up his own divorce in the piece (why should he?), but for all any of us know, his experience of the breakdown of his own marriage and its aftermath taught him a lot about how few resources nuclear families have to rely on when the husband and wife run into trouble. As I’ve said, personal experience of the breakdown and end of a marriage — one between two Christians who did not cheat on each other, and who never imagined that divorce would be an option for us — taught me a lot about how difficult and complex life is, and how events outside of one’s control can break you. In fact, in our case, you can point to factors within the broad families on both sides — the kind of “extended families” that used to hold people together — that led to the collapse of our marriage. Paradoxical, eh? But it happened. It really did.

Look, lots of conservatives hate David Brooks. I get the sense from context here that there’s particular anger among some conservative Evangelical intellectuals, because both David and his wife are involved in Protestant anti-Trump intellectual networks. I don’t understand those dynamics, and as an outsider, wouldn’t presume to judge.

I have not been in touch with either of the Brookses about this, and they might actually prefer that I hadn’t written. But dammit, I get fired up when people pass judgment on divorced people without knowing what really happened in the divorce — especially when they base their judgment on something I know for a fact isn’t true.

Possibly related: in talking with an Orthodox priest yesterday in Norway, he told me that most people have no idea how pornography is destroying the minds and souls of people — not just in terms of what it does to them individually, but also in how it makes it hard for them to form stable romantic relationships, and start families. He said the view he gets as a priest who hears confessions is very different from the general sense that most people in our society have. Even normal people who understand that pornography is a problem really don’t grasp the depth of the destruction. If they did, they’d want to ban it.

I bring that up here simply to say that life is so much more complex than most of us think. I told a story to some Norwegians over the weekend about how I was in Budapest when the Russia-Ukraine war started, and learned a lot from Hungarians opposed to NATO involvement in the war why they felt the way they did (a feeling not shared at the time by most Europeans). When I’ve been back to the US over the years of the war and discussed the war with my fellow conservatives, more often than not I would run into a wall of anger and willful refusal to consider that the situation might be a lot more complicated than they preferred to think. For them, it was simple: Russia evil, Ukraine saintly. Anybody who denied that narrative was obviously a Putin stooge.

Final point: one more time, I often disagree with David Brooks’s political and cultural views, and have at time expressed that disagreement in this space. So what? I still like and respect him, and believe him to be a good man — not a perfect man, but then, who is? Not you, and not me. His arguments stand or fall on their own merits, not on whether or not he did right by his ex-wife, or was wrong to marry his former assistant. If you don’t believe that, and if you are going to start judging the intellectual arguments of individuals on the basis of their personal lives, then you are going to have a lot of reassessment to do.

Some of the wisest men and women I have known have been those with messy personal lives. Some of the most foolish have been people who have lived irreproachable personal lives. As you know, I’m reading a lot of Weimar history now, and encounter individual cases like that of the fictional Paul Baumer, in the novel All Quiet On The Western Front: men who fought in the trenches, and who knew how horrible war was, would come home and listen to the patriotic cheerfulness of those far away from the front, and be disoriented by the chasm between what the front actually was, and what the home folks wanted it to be.

Similarly, I remember once an Iraq War veteran friend in Louisiana telling me that he and his vet buddies hated people coming up to them to say “Thank you for your service” — and felt kind of guilty for that. Vets like him, he said, knew that these people genuinely meant well, but he also knew that they had no idea what the vets had been through, and how a more or less sentimental view of war and patriotism had had a lot to do with them (the vets) being sent to Iraq in the first place. He was a rock-ribbed Rush Limbaugh-listening right-winger, but he said his experience in Iraq taught him a lot about the lies we Americans told ourselves about that war.

On Friday night in Oslo, I was sitting at a table with some Norwegians, one of whom was of Afghan descent, though a naturalized Norwegian. This person served in the Norwegian armed forces in Afghanistan, alongside Americans. The vet said it was shocking to listen to American comrades in arms say things like, “We’re not going to leave this country until all the women are free, democracy is stable, and the economy is on a stable path to success.” Knowing Afghan culture — this veteran’s family had fled it — the Norwegian soldier said the deeply sincere, good-hearted naivete of the Americans was deeply shocking. Said this ex-soldier: “They really believed all that.”

The point is this: sometimes the truth — truth only learned from experience — plays havoc with one’s principles, no matter how strongly and sincerely held. It is the conservative conceit that we try to understand the world as it is, not as we would like it to be. I hope that the good Christian conservatives kicking David Brooks never, ever have to experience what he did, whatever his role might have been in the breakdown of his marriage (and for the last time, it is not what people who don’t know these people think it was). You might think it can’t happen to you. I’m here to tell you, from painful experience, that it can.

I’m going to send the part above to the whole list. Subscribers, read on for commentary on a terrific essay I read last night about men, women, and why we can’t find each other as romantic partners. This is the kind of piece that future historians will look back on to understand how we managed to destroy our civilization.