Democracy In The Ruins

Dante, Walker Percy, and How All Political Problems Are Ultimately Religious Ones

Collin Slowey says we should all read Walker Percy’s dystopian novel Love In The Ruins, which takes place in a future America that has torn itself in two. Slowey writes, in part:

At the end of Love in the Ruins, the protagonist’s priest encourages him to focus less on himself and his ideas and more on things like “doing our jobs, . . . showing a bit of ordinary kindness to people, particularly our own families, . . . [and] doing what we can for our poor unhappy country––things which, please forgive me, sometimes seem more important than dwelling on a few middle-aged daydreams.” In our current age of obsessive media consumption, news reading, and opinion sharing, this is good advice. Political polarization is a serious problem, but it cannot be solved by becoming ever more extreme. The path forward, for us as it is for Tom More, lies not in criticism and activism but in acquiring a proper perspective and fulfilling basic social duties.

Love in the Ruins speaks to our present moment in the United States like few other books. From the state of the political parties to divisions within the Catholic Church to the renewal of racial tensions, Percy’s predictions are eerily accurate. Even more important, though, is what Percy has to teach us about the dangers of moral superiority, ideological idealism, and the capacity of intellectual humility and hard work for achieving genuine progress. In this divided, contentious time, we would do well to revisit this classic work––and take its lessons to heart.

I mentioned the other day, either on my blog or in this space, how taken aback I was by going to vote the other day, and realizing as I stood in the voting booth that with the exception of the mayoral race, I knew nothing about any of the down ballot local races. I didn’t even know who the candidates were. I could not possibly be more disconnected from what’s going on locally — this, though I can tell you all kinds of things about national politics. There’s something wrong with that.

I was talking the other day to a friend of mine who works in Democratic politics. He lives in a very red state, and is an ethnic minority. He is very passionate about his work, and very much on the Left. And he told me some of the stuff he has had to suffer from people in his own town for being dark-skinned and a Democrat (so identified by a bumper sticker on his car). But he said he is also involved in a non-partisan civic organization locally. He said that it has been a good exercise for him to rub shoulders with people who do not share his politics or outlook on the world, and to see that they can also be good people who want the best for their communities, and who do practical things to make it happen. He didn’t say this, but I thought that those white people in that group are probably learning the same thing about him.

This is a guy who is far, far more passionate and political than I am, yet he is also political in the more everyday sense, of wanting to be involved improving the polis in which he lives. What a good example he sets. I have always been the kind of person who loves to stand back and analyze, but resist getting involved — not for any particularly negative reason, but just because I’ve never been a joiner. If I’m honest, I have to admit that there’s something wrong with this.

The fact is, American society today is far more characterized by people like me than people like my friend. This was the fundamental point of the Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam’s famous book Bowling Alone. Putnam demonstrated that since the 1960s, American society has become far more individualistic, and far less civic-minded. People of my parents’ generation joined civic organizations. That began to change with the Boomers aged, and seriously declined in my generation, and subsequent ones. There are many reasons for that, and I won’t go into them here, but the indisputable fact is that we have become a far more atomized society.

I was re-reading today Canto XVI of Dante’s Purgatorio, in which the pilgrim Dante arrives on the Terrace of Wrath, where the sin of anger is purged. It’s one of the most important cantos in the entire trilogy, coming as it does near the dead center of the journey. I’m planning to write about it at length on Monday on my blog, but I’ll say here that the pilgrim Dante arrives and meets in the smoke and ashes someone named Marco. Dante asks him to explain how the world got into such a mess (Dante comes from Tuscany of the early 14th century, where cities rose up against each other, families turned on the kin, and the Church was rotten with politics).

Marco tells the wayfarer that people in the world have abdicated their personal responsibility. They blame everyone but themselves for the disorder, but this is a self-serving lie. Yet Marco goes on to say that the people do suffer from a lack of good leadership to guide them in forming their inner desires in harmony with virtue.

One interesting aspect of this is that Dante (the poet) writes at what we now know was the tail end of the Middle Ages, a point in which the entire theological, philosophical, and political system of which Dante was at the apex was about to collapse. The literary critic Erich Auerbach, in his classic work Dante: Poet of The Secular World, observes that Petrarch was only forty years younger than Dante, but was a man of the new age. Dante’s generation was the last one to understand the world and man’s place in it in terms of cosmos — that is, a finite construct that was ordered, and had what C.S. Lewis described as “a built-in significance.” In Dante’s Commedia, we see that people fall into disorder when they lose sight of the big picture, and follow their individual passions instead of holding to the clear path of virtue. This is why the pilgrim Dante finds himself “in a dark wood” at the poem’s opening, “for I had lost the straight path.”

Petrarch, though, was a new kind of man — the first modern, we might say. As Auerbach explains, Petrarch did not submit to an outside order or authority. “He is distinguished from Dante above all by his new attitude toward his own person; it was no longer in looking upward,” writes Auerbach, “that Petrarch expected to find self-fulfillment, but in the conscious cultivation of his own nature.”

This emergence of “the autonomous personality,” says Auerbach, gave us the Renaissance, the Reformation, and, eventually, the modern world. “From Christianity, whence it rose and which it ultimately defeated, this conception inherited unrest and immoderation,” Auerbach notes. Dante’s incomparable work is a kind of cathedral constructed by a religious vision that had lost its hold on the world.

If you haven’t read the Commedia, then it’s important to understand that Dante is absolute murder on the corruption in the Church — Boniface VIII is the Darth Vader of the poem — and in contemporary political life. This is why he has Marco, in Canto XVI, blaming bad leadership for the disintegration of society into violence, even as Marco counsels that the power of renewal lies in the hearts of all men.

What does this have to say to us today? I’m going to need to think about it before I write more, but it seems to me that we are a people who are hard to lead, because we are so unwilling to surrender our autonomy to the rule of any other figure, ideal or system. But this isn’t the whole story, because as the noted Minnesota philosopher Robert Zimmerman has said, “You gotta serve somebody.” All of us have a telos, whether we are aware of it or not. Our problems have a lot to do with the fact that we can’t agree on what that telos is, and we live in a world constructed for us by technology that allows us to think that the world is whatever we imagine it to be — and that when reality contradicts us, then it is someone else’s fault that we have been unjustly treated. If we moderns are, as Walker Percy posited, lost in the cosmos, maybe it’s because we no longer believe in the cosmos. We no longer believe that truth is out there, and is discoverable, and knowable. Dante would have said that a world in which people could only know themselves, and only wanted to know themselves, is a world that politically is bound to end up a lot like the City of Dis — the infernal New Jerusalem.

In the end, all political problems are one way or another religious problems. But maybe the thing to do is to think less about this stuff, and to act more charitably. I’ve told the story about when I was just becoming interested in becoming a Catholic, back in 1991, and a Catholic colleague at my workplace invited me to join her that weekend volunteering at the Missionaries of Charity soup kitchen downtown. Mother Teresa’s nuns? That seemed very Catholic to me, so I agreed.

I spent that afternoon scrubbing pots, chopping carrots, and doing mundane things. I never had a theological conversation with a nun, received mystical words of wisdom, or anything that I had hoped for. When it was over, I thought, well, that was nice, but I’m more of an intellectual, and my time would be better spent reading books about God.

I did become a Catholic in 1993, but by 2006, after four years of spiritually and emotionally excruciating work covering the abuse scandal, I had no Catholic faith left in me, and left the Church. Reflecting in the ruins of my Catholicism, trying to figure out how it had happened to me, I thought at one point that my intellectualism, my weakness for abstraction, had left me particularly vulnerable to things within the Church that negated my ideals. If only I had read fewer books, and gone to serve the poor by scrubbing pots and chopping carrots at the soup kitchen, my faith might have proved more resilient in the face of crisis.

As it was for me and Catholicism, so it might be for all of us and democracy.

I told a story in this space the other day about being in Paris in October 2012 with my daughter Nora, who was six at the time. I was looking through old photos of that trip this morning, and ran across one of my son Lucas, then eight. There’s a funny story attached to it.

Lucas was the only one of us who was not interested in going to Paris. He’s a homebody, and didn’t see any reason why we should go spend a month in some foreign place when West Feliciana Parish is perfectly fine. He’s my dad’s grandson, for sure.

On one of our first days in the city, we found ourselves near the Pompidou Center, where Paris’s modern art museum is. None of us are particularly fond of modern art, but it was raining, and we were there, and we had museum passes, so why not go? Lucas put his foot down: he did not want to waste time looking at art. Art is stupid, according to Lucas Dreher, age eight.

His mother and I told him to straighten out his attitude, and to accept the fact that we were all going to be in this museum for the next couple of hours, and that he had better not yuck everybody else’s yum. Fuming, he got in line.

It didn’t last. Not long into our museum visit, Lucas started complaining. “Stop that right now,” I said. He didn’t stop. He went over to his mother and kept it up. “You stop that right now,” she said. But he didn’t stop.

Finally, I had enough. I sternly told him to go sit on that bench over there, by that big painting, and not to move, or say another thing to us. He could be as miserable as he wanted to be, but he wasn’t going to ruin the museum for the rest of us. Lucas stomped over to the bench and plopped himself down.

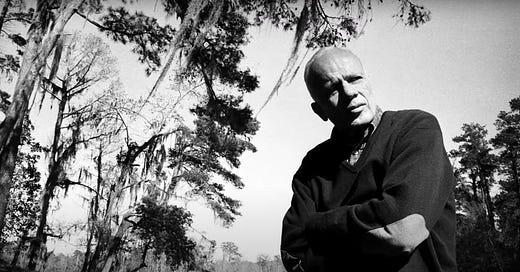

A few minutes later, I walked over to check on him, and had to suppress a laugh. Here is what I saw before me (forgive me, but I had to black out his eyes; I don’t like photos of my kids on the Internet):

There was this completely sour-faced little boy, a suck of misery, sitting in front of a spectacularly exuberant painting! If you could see his eyes, you would be staring at a child’s contempt so pure as to be comic. He was looking only inside himself, at his boredom and frustration, not outside at the beauty all around him. But then, Lucas was only a kid. What’s our excuse?