Democracy's Fall Is A Choice

And: This Week In European Civilizational Erasure; Kelvin, The Blind Man Who Sees

Here’s a First World Problem for you: on the train back from Bratislava, I received a message from my hotel that I had left my Kindle in my room. NOOOO! NOT MY PRECIOUSSSS! I really do depend on it second only to my laptop to do my work. We explored every possible option to get it back to me via courier before I leave for Norway on Friday, but nothing could be guaranteed.

So I had no choice but to turn around once in Budapest, and return to Bratislava, two and a half hours away, and retrieve it, all the way heaping coals of condemnation on my head. Cost: $100 for the train tickets, and six hours of the day. Why can’t I go anywhere without leaving behind or forgetting to bring something?

“You need an assistant,” a sympathetic friend said.

“I had one,” I replied. “She put me out.”

Well, at least all that train time yesterday gave me the chance to get more reading done. I read German historian Volker Ullrich’s Fateful Hours: The Collapse Of The Weimar Republic. (One advantage of the Kindle is that you can read Amazon’s digital books across devices, including your laptop.) It was meticulously detailed — frankly, almost to the point of tedium, for its intense focus on the political and parliamentary maneuvering that led to Hitler’s takeover. Still, it was well worth the read. Though I’m more interested in the broader cultural picture of 1920s Germany, and how that contributed to the political fate of the nation, I’m learning a lot through reading the same basic story through a number of different eyes.

Ullrich begins:

We should constantly recall that the Weimar Republic didn’t go out with a bang. It was gradually undermined by the erosion of the constitution and democratic practices. This “quiet death” should serve as a negative example of how Western democracies like the United States, whose stability has long seemed unshakable, could fail despite their long and storied tradition. The failure of the Weimar Republic remains a lesson of how fragile democracy is and how quickly freedom can be squandered, if democratic institutions cease to function and civil society is too weak to keep the anti-democratic wolves from the door.

Very true. His narrative shows that the Nazis stumbled many times in the 1920s, and even as late as 1932, could have been stopped, had individuals in power made different choices. The wealthy conservatives around elderly president Paul von Hindenburg didn’t like the Republic in the first place, and thought they could use Hitler to put an end to democracy, but keep him on a tight leash. Over and over, they failed to take the true measure of him and what he represented. They were social elites, and simply couldn’t grasp that a rough customer like Hitler was capable of doing much harm.

Plus, the Communist Party of Germany repeatedly refused to stand its candidate down in key elections, drawing away the leftist vote that would have gone to the Social Democrats — the mainstream party which, had it won, would have kept the Nazis out of power. Towards the end of the 1920s, partly at the direction of Stalin, they called the Social Democrats “social fascists,” and voted Communist, even though they knew they had no chance of winning.

Though my eyes glazed over at Ullrich’s blow-by-blow account of the parliamentary politicking of late Weimar, it was useful to see how the squabbling and scheming among German parliamentarians, even as the German people were desperately suffering from the Great Depression, caused more and more ordinary Germans to lose faith in democracy, and turn to a strongman as savior. Ullrich stops the narrative at certain points, even as late as 1932, the year before Hitler was made chancellor, and democracy quickly ended, to point out that if only the fools at the top of German politics had not been so blind and selfish in a given moment, history would have gone in a very different direction.

His point is that Nazism emerged out of very real social and economic conditions, but that Hitler’s taking power was not inevitable.

Now, I remember that when Trump first came to power in 2016, we saw a number of liberal books positing him as a fascist who was going to end democracy. Weimar was invoked. Well, it didn’t happen, and even Trump critics and skeptics from the Right figured that panicked response was overblown. (Remember the Washington Post’s new slogan, “Democracy Dies In Darkness”?)

What none of those books and arguments did, at least as I recall, is to look at the entire picture of contemporary American conditions, and how they were eroding democracy and leading to illiberal authoritarianism. Specifically, given the biases of the authors, they saw the threat as coming entirely from the populist Right. What I’m going to do with my upcoming book is to show that yes, the Right today is contributing to the problem, but it has been, to this point, chiefly driven by the illiberal Left. You got a dose of that in Live Not By Lies, it’s true, but in this new book, I’m going to take a broader view at what both sides are doing, and failing to do, but also examine the social and cultural conditions that are demolishing the guardrails of democratic governance.

For example, I had not quite realized until reading Ullrich how much material inequality contributed to the rise of the Nazis. Even as ordinary German people were suffering from mass unemployment, sickness, and real hunger, the super-rich Germans took care of themselves. In fact, towards the end of Weimar, which was at the height of the Great Depression, industrialists intervened with conservatives running the government, and its austerity program, to put the brakes on programs to help the hungry and desperate, calling them all “Marxist”.

The point is not that people are starving in America today, and the Fortune 500 doesn’t care about them. The point is that if income inequality reaches a certain point, the masses begin to lose faith in the system.

And then there was the trauma of having faith in everything that came before it shattered by the war. Thus, New Year’s Eve 1918:

Historian Gustav Mayer, who sympathized with the MSPD [moderate Social Democrats] politically, drew a similar conclusion: “The collapse is not just of the ruling class and a political system. It’s simultaneously the moral collapse of an entire people, a destabilization of all its standards, a seismic disturbance of all its values, a questioning of all moral relations and all duties. We’re living on the day after an unprecedented earthquake, uncertain whether the last blow was indeed the hardest and whether it makes any sense to start rebuilding the rubble.”

Powerful lines! As I keep saying, we in America haven’t lived through that kind of sharp, relatively sudden shock that undermined all our values and social structures. But we have lived through a slow-motion erosion and destabilization over the past few decades, of the moral standards, practices, and ways of thinking necessary to support responsible self-rule. I’m going to demonstrate that in the book. Thinking Germans in 1918 saw what had happened, because it happened so quickly. We have been like the proverbial frog in boiling water. Our relative prosperity has anesthetized us to this process.

For example, if you read The Benedict Option, you might recall the sociologist of religion Christian Smith discussing the spiritual lives of what he called “emerging adults” (those aged 18 to 23). In research published in 2009, Smith found (the quote is from The Benedict Option):

An astonishing 61 percent of the emerging adults had no moral problem at all with materialism and consumerism. An added 30 percent expressed some qualms, but figured it was not worth worrying about. In this view, say Smith and his team, “all that society is, apparently, is a collection of autonomous individuals out to enjoy life.”

(Lately I see on X that some right-wng stalwarts of the pre-Trump Republican order are cracking hard on Patrick Deneen as somehow guilty of tearing down liberal democracy with his 2018 book Why Liberalism Failed, and subsequent work. This is like blaming the oncologist for the cancer. A society in which most people believe that society is nothing more than a collection of autonomous individuals out to enjoy life is a society in which liberalism — seen as the liberation of the choosing individual from every non-chosen obligation — cannot sustain itself over the long term. Christian Smith reported these data eight years before Why Liberalism Failed was published.)

It didn’t take losing a Great War to reduce Americans to this. It took sustained prosperity, a loss of binding religious faith, and the embrace of a therapeutic, hedonistic culture, over a long period of time, to bring it about. The result is the same, though: to rob people of the internal dispositions necessary for democratic self-rule. One should never tire of pondering John Adams’s famous quote about our Constitution being insufficient to govern people who have lost the moral and religious sense. That is to say, a structure of classical liberal self-government depends on the internalized moral order and self-discipline of the people living under the system.

The Germans won their democracy in 1918, with a swift revolution that overthrew the Kaiser after Germany’s loss in the Great War. Most people were initially thrilled by the advent of democracy, but that did not last. Ullrich:

Ernst Troeltsch, like Kessler an attentive observer of the times, identified a “wave from the right” in December 1919, particularly at German universities: “If you spoke to students a year ago, you had to be prepared for offbeat, pacifist, revolutionary, even idealistic Bolshevik contradictions. Today you have to be ready for antisemitic, nationalist, antirevolutionary backlash. In some legal faculties, people scuffle their feet in displeasure whenever the word ‘constitution’ is mentioned.” In fact, faced with economic hardship and bleak career prospects, most German students turned their backs on the republic. It was one of the most serious flaws of Weimar democracy.

The other day I wrote in this space that the Nazis, in the 1920s, found a lot of support among middle-class young men, especially university men, who were terrified about their futures, and scared nearly to death about being being “proletarianized” — that is, reduced to the economic precarity of the working class. We absolutely have this today, with the younger generations, even amid the kind of general prosperity unknown to Germany in the aftermath of World War I. You see what I’m getting at?

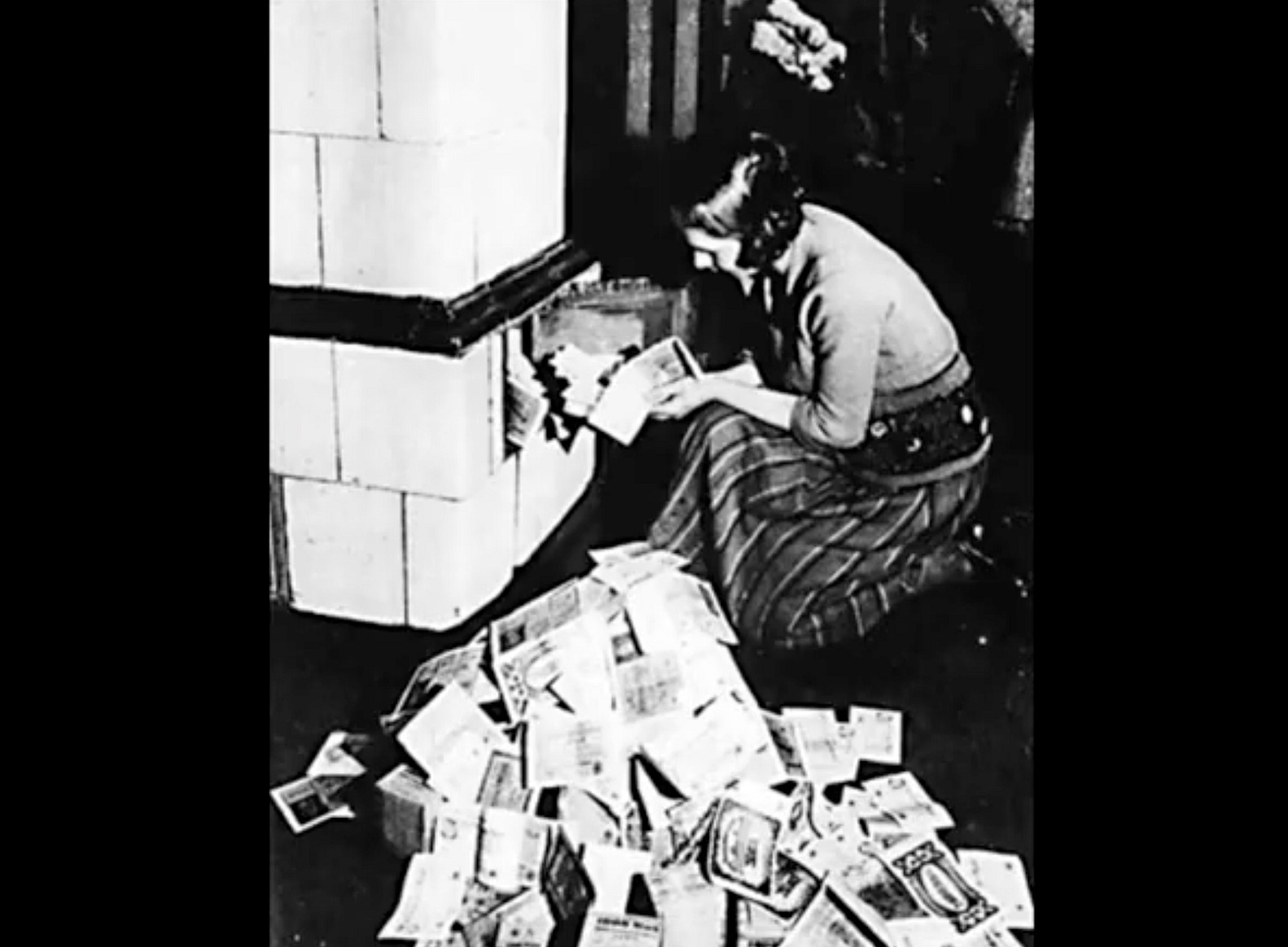

I wonder how many right-wing radical young men today were children when the economy crashed in 2008, and who had to live through the loss of their family home, or in some other way observed their parents struggling to keep a roof over their family’s head. As bad as that was, it was nothing compared to what happened in Germany under hyperinflation.

In one case of young German men tried for right-wing political violence in the 1920s:

The majority of the seventeen men in the dock were young, mostly university and high school students. They all came from so-called good homes and had deviated from the straight and narrow amid the turmoil of war and the immediate postwar period. Disoriented and insecure, they had sought refuge in nationalist and right-wing extremist organizations.

The violent Left — the Communists — were almost always of the working class. In our society, you aren’t going to find many working class people aligned with Antifa and its fellow travelers. The point is that precarity drives some people, “disoriented and insecure,” into the arms of anti-democratic extremists who give them purpose in part by telling them who to hate, and by resolving their anxieties through scapegoating and violence.

One more Ullrich quote about all this — and remember, he’s talking about the immediate postwar period of hyperinflation:

Germany’s currency wasn’t the only thing in precipitous decline. Social norms and morals also lost their validity. Mainstream values such as reputability, decency, and civic responsibility no longer counted for much. Many Germans turned unscrupulous, cynical, and selfish. After the trauma of war and revolution, people now had to witness “the daily spectacle of the failure of all the rules of life and the bankruptcy of age and experience,” recalled journalist Sebastian Haffner about being a sixteen-year-old schoolboy in Berlin in 1923. Germany lost faith in the status quo. What could still be relied on, given all that had happened? Like many members of his generation, seventeen-year-old Klaus Mann, Thomas Mann’s eldest son, asked himself: “With everything around us crumbling and shaking, what were we supposed to cling to, what laws were we supposed to follow? . . . We were introduced early on to apocalyptic moods and became quite experienced in dissipation and excess.”

In our case, having lost so much in the ways of our values and convictions, and economic stability, can you imagine what a grave economic crisis would do to America? You don’t have to imagine: look at what happened to Germany, which prior to losing the war had been a socially stable, sober society.

Much more below for subscribers. This is important stuff, with direct relevance to our situation today in America…