So, the presidential race has been decided. Good. It was exhausting. Honestly, I don’t know how anybody, liberal or conservative, can bear to live with cable television news on all the time. For the last decade or so, we have had a television in our house, but it is only connected to Amazon for streaming, and Netflix. I only have to see cable news when I am at the garage getting my car serviced, or a place like that. The noise of it is what is so unsettling. The world it presents to us is designed to hold our attention, which discourages reflection. It’s a banal observation, I know, but it doesn’t feel that way if you live outside that information bubble, and are then exposed to it on occasion.

A few years ago, I was talking with a liberal friend about how wearisome it is to try to have a conversation with my mom, who watches a lot of Fox News, not so much because she ends up reflecting the opinions of Fox presenters, but because all that cable news keeps her in a state of constant agitation. Why should a little old lady in rural Louisiana be so het up over Benghazi? He told me that his mother, a liberal, is exactly the same way, but with MSNBC. He actually agrees with her politics, but cannot bear much of her anger and anxiety.

But I have to be careful not to judge too harshly. I don’t watch cable TV, but I do check Twitter incessantly. I cannot handle waiting in line at the grocery store without pulling my phone out to see what people are saying. I can’t think of the last time I was able to stop at a red light for more than two seconds without reflexively reaching for the phone. This is nuts! But that’s how we live today.

In 2016, Tim Wu of Columbia University published a great book titled The Attention Merchants. It’s kind of a history of advertising in the mass media age (that is, from the late 19th century to now), but it’s actually more interesting than that. It’s about a technological arms race in which advertisers compete to see who can control the attention of buyers. Wu writes about how the advent of the Internet and smartphone technology was a defining civilizational moment. No one had ever been able to get inside our heads quite that way. He writes:

But with the new horizon of possibilities has also come the erosion of private life’s perimeter. And so it is a bit of a paradox that in having so thoroughly individualized our attentional lives we should wind up being less ourselves and more in thrall to our various media and devices. Without express consent, most of us have passively opened ourselves up to the commercial exploitation of our attention just about anywhere and anytime. If there is to be some scheme of zoning to stem this sprawl, it will need to be mostly an act of will on the part of the individual.

Wu talks about how hard this is to do. The “attention merchants” have a vested economic interest in keeping us constantly plugged in, seeking out another hit of dopamine (Wu, like Shoshanna Zuboff in her 2019 book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, points out that attention merchants keep neuroscientists on the payroll to figure out better and faster ways to control us.) We have all habituated ourselves to the constant noise. I haven’t ever been much of a TV watcher, so over the years, when I would be in town visiting my folks, I would have to ask them to turn the TV off so we could converse. I was not used to the TV being on constantly, and I couldn’t follow conversation with it flickering away like a hearth. My parents kindly honored my request, but I could tell how jittery the silence made them. They weren’t used to it.

Again, I can’t be too high and mighty about that, because I find it easy to do without TV, but much harder to do without checking Twitter and e-mail. Am I really so much better? Nick Carr, in his much-heralded 2011 book The Shallows, explained how the Internet affects our brains and our cognitive processes — and it’s not good. More recently, Carr penned an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal (paywalled) in which he described how smartphones hijack our brains. Excerpt:

In an April article in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, Dr. Ward and his colleagues wrote that the “integration of smartphones into daily life” appears to cause a “brain drain” that can diminish such vital mental skills as “learning, logical reasoning, abstract thought, problem solving, and creativity.” Smartphones have become so entangled with our existence that, even when we’re not peering or pawing at them, they tug at our attention, diverting precious cognitive resources. Just suppressing the desire to check our phone, which we do routinely and subconsciously throughout the day, can debilitate our thinking. The fact that most of us now habitually keep our phones “nearby and in sight,” the researchers noted, only magnifies the mental toll.

Weirdly, the smartphone gives us the illusion that we’re more informed than ever, but the opposite may be the case. Carr:

As Dr. Wegner and Dr. Ward explained in a 2013 Scientific American article, when people call up information through their devices, they often end up suffering from delusions of intelligence. They feel as though “their own mental capacities” had generated the information, not their devices. “The advent of the ‘information age’ seems to have created a generation of people who feel they know more than ever before,” the scholars concluded, even though “they may know ever less about the world around them.”

That insight sheds light on our society’s current gullibility crisis, in which people are all too quick to credit lies and half-truths spread through social media by Russian agents and other bad actors. If your phone has sapped your powers of discernment, you’ll believe anything it tells you.

You know, I read things like that, am alarmed by them, then go back to my life with the smartphone and the Internet. I am like the two-pack-a-day smoker in 1965 who reads about the Surgeon General’s report, believes it, but changes nothing.

Here’s something strange I’ve noticed: I have dramatically diminished capacity to read print magazines. My wife today found a pile of magazines to which I subscribe, some of which had never been taken out of the wrapper. “What’s the deal here?” she asked. The deal is that if those magazines were available online, I probably would have read them. But they’re not, so I haven’t. I intended to read them, but there’s always something to read on my browser.

These are good and interesting magazines, too! I paid for them! So why do they sit unread? Probably because to pick up a magazine and read it means that I can’t instantly click over to see who is messaging me, or what’s in my e-mail, or what’s on Twitter. It means I have to commit to the magazine itself. I find that so difficult to do now for any length of time. Same with books.

The truth is, I have to be wired to do my job. I really do. But if I were to win the lottery, I would commit myself to going cold turkey, if only to rebuild my cognitive focus, as well as to re-learn to see the world as it is, not as how it feels, if you follow me. My friend the English writer Paul Kingsnorth lives with his wife and children in rural County Galway, Ireland, where he has sought disconnection with the modern world, heavily conditioned by electronic media. Watch this Dutch TV documentary about Paul and the life he has built in rural Ireland. It seems awfully attractive to me. Living with distance from the Internet and social media cloud, Paul not long ago produced an eerie and profoundly unsettling short story, “The Basilisk,” in which he theorizes that the best way to understand what social media and the Internet are doing to us is as a form of demonic possession. From the story (it’s written in the form of letters between an old scholar and his niece):

In order for temptation to work, morals must be corrupted and boundaries dissolved. This is why the Ten Commandments exist, and the Seven Deadly Sins. I realise I am starting to sound like a vicar. I am using Christian examples because I think they may yet have some cultural purchase with you, but you’ll find similar injunctions in many traditions. They are aimed at leading us not into temptation. Once the boundaries are gone, you see Bridget—once we say hell, why not? to anything we are offered—well, then we are clay in their hands.

In short, the sequence runs: moral corruption—temptation—enslavement. This is the way the demons have always worked. How then, if you were one of them, would you start? How to weaken us, take us away from good and pull us towards darkness? How to lead us towards the endless fulfillment of our ego-desires? How to change our behaviour towards each other: make us more suspicious and mean-spirited, bring out the worst of our judgmental, bullying tendencies? How to suck us so far into our own heads, and so far from measurable reality, that we can no longer tell the difference?

What tool could you possibly invent to achieve these things, Bridget—and to achieve them without the victims even realising? That is the key, you see. The slave must believe he is free, or the plan fails. If people know they are oppressed, they will rebel in the end. If they believe their oppression is actually liberation, they are yours forever.

Can you see now where I am pointing?

Read it all — it’s important. And by the way, Paul’s wonderful new novel Alexandria, in fact, is set among a pagan remnant living in dystopian England a thousand years into the future. Paul has deep insight into how myth and religion tell us forgotten truths about who we are, and how we should live in harmony with our bodies and the natural world.

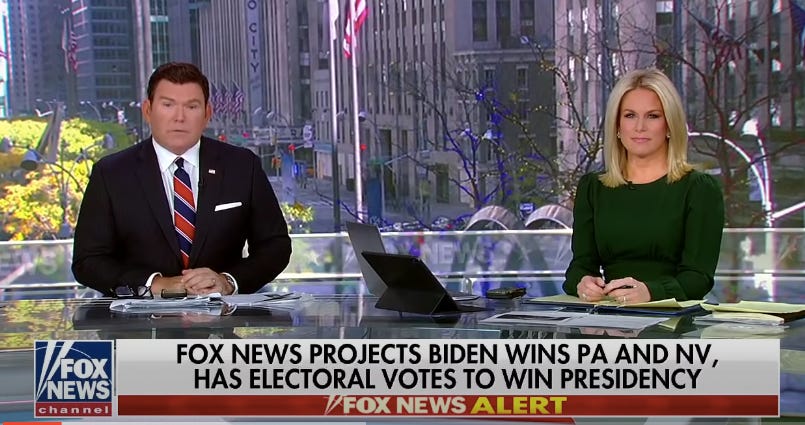

Today I received a sad message from a grieving friend. He has been alienated from our politics for a while, and has watched his Facebook feed with growing alarm as friends and family give themselves over to acidic passions. When the media declared Joe Biden the winner of the presidential race, his sister sent out a wildly celebratory message to everyone on her list. He wrote her back to say he couldn’t share her joy, because he has a bad feeling about where the country is headed, and would have felt exactly the same way had Trump won. She responded by cursing him, and telling him, “You are dead to me.” She and her children severed their relationship with my friend — thus, in my view, vindicating his sorrowful judgment about the state of the country.

Would people have treated family members like that without the effect of social media, conditioning us to the dopamine hit? I wrote earlier this week about having dinner on Thursday night with a Democrat friend, who was really down about all the caustic commentary he had been reading on his Facebook feed from his Republican friends. It felt personal to him. I encouraged him to get off of Facebook. It’s a matter of saving the relationships that matter.

One more comment about Tim Wu’s book. He writes that traditional religion, especially monotheistic ones, placed control of one’s attention at the heart of spirituality. The decline of religion in the 20th century is connected to this disintegration of our attentiveness, he theorizes:

To be sure, it sin’t as if before the twentieth century everyone was walking around thinking of God all the time. Nevertheless, the Church was the one institution whose mission depended on galvanizing attention; and through its daily and weekly offices, as well as its sometimes central role in education, that is exactly what it managed to do. At the dawn of the attention industries, then, religious was still, in a very real sense, the incumbent operation, the only large-scale human endeavor designed to capture attention and use it. But over the twentieth century, organized religion, which had weathered the doubts raised by the Enlightenment, would prove vulnerable to other claims on and uses for attention. Despite the promise of eternal life, faith in the West declined and has continued to do so, never faster than in the twenty-first century. Offering new consolations and strange gods of their own, the commercial rivals for human attention must surely figure into this decline. Attention, after all, is ultimately a zero-sum game.

I think of myself last night, in the darkness of my bedroom, relieved to have finished my nightly prayer discipline so I could check Twitter one more time before falling asleep.

It would be dishonest if I let this topic slide without a shout of gratitude for the kinds of connections the Internet has allowed us to make. I received a lovely e-mail from a new subscriber to this newsletter who lives in Paris. He writes, in part:

Christendom is indeed guttering out...slowly, painfully numb, with what one might consider a death wish like sorrowful ignorance. God only knows where this is finally going...

So we pray our rosary during this Covidtide lockdown and remember St. Augustin when he confidently stated to his flock, that men build cities and men destroy cities, yet the city of God is eternal!

Rod, he continues to work in mysterious ways...we only need His eyes to see beyond the folly before us.

I look forward to meeting you one day.

If you like and have the time, we can road trip to oyster heaven in Bretagne for a day or two...Plenty of medieval and WWII history en route through Normandy to experience. A pilgrimage of sorts!

Absolutely! As soon as the shadow of Covid Mordor is banished from the land, I’ll be off to France to renew old friendships, make new ones, and eat, drink, and pray.

Over at my TAC blog, I used to have a popular feature called View From Your Table, in which I would publish readers’ photos of their meals in context. James C. was the absolute master of the genre. I hereby revive it on this newsletter with an entry from James C., who is back in Italy:

He sends the photo above with the following commentary:

At a nice, ordinary Ligurian friggitoria (fry place). Crispy calamari, shrimp and anchovies (fresh anchovies from the Ligurian Sea are nothing like any you’ve tried). A spinach torta (sort of a quiche-like thing). Sardinian beer.

It’s November, the sun is shining, lemons are growing in the trees. Liguria is not (yet) on lockdown. Blessed.

Here’s where he is:

Please send your VFYT photos to roddreher@substack.com. The rules for the feature are simple, but I have to be strict in following them. This is not meant to be a photograph of your food alone. Don’t stand over the table, point your camera down, and click. Rather, this is meant to showcase what you are eating in a context that says something about the place in which you dined. There is James, eating fried seafood under a lemon tree in a Ligurian courtyard. I have a hard rule about not featuring faces in the shots, but it’s okay when they are far enough in the background (as in the above shot) to be indistinct.