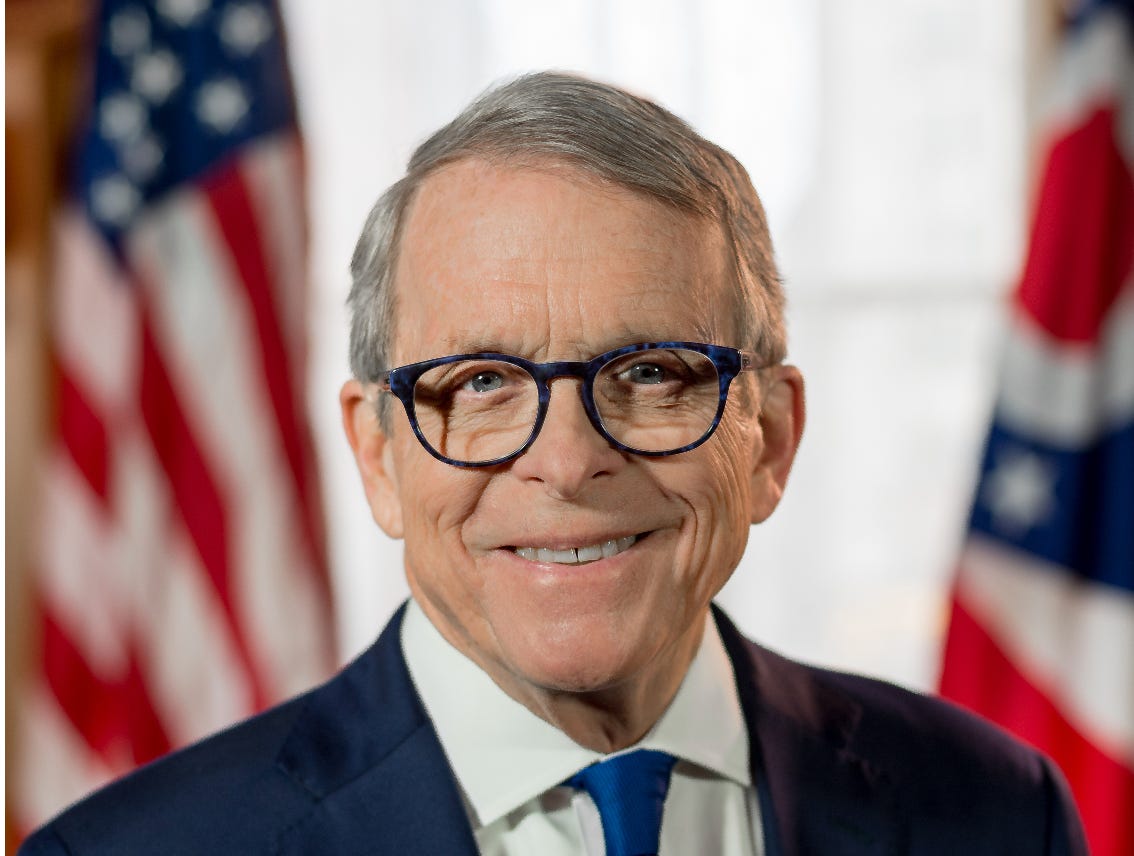

Gov. Mike DeWine (R-Donor Class)

On the betrayal of children by Ohio's pro-trans governor

Gotdoggit, y’all, here I am in blissfully rainy England, and events have dragged me out of my Nativity idyll to rant. But this is important.

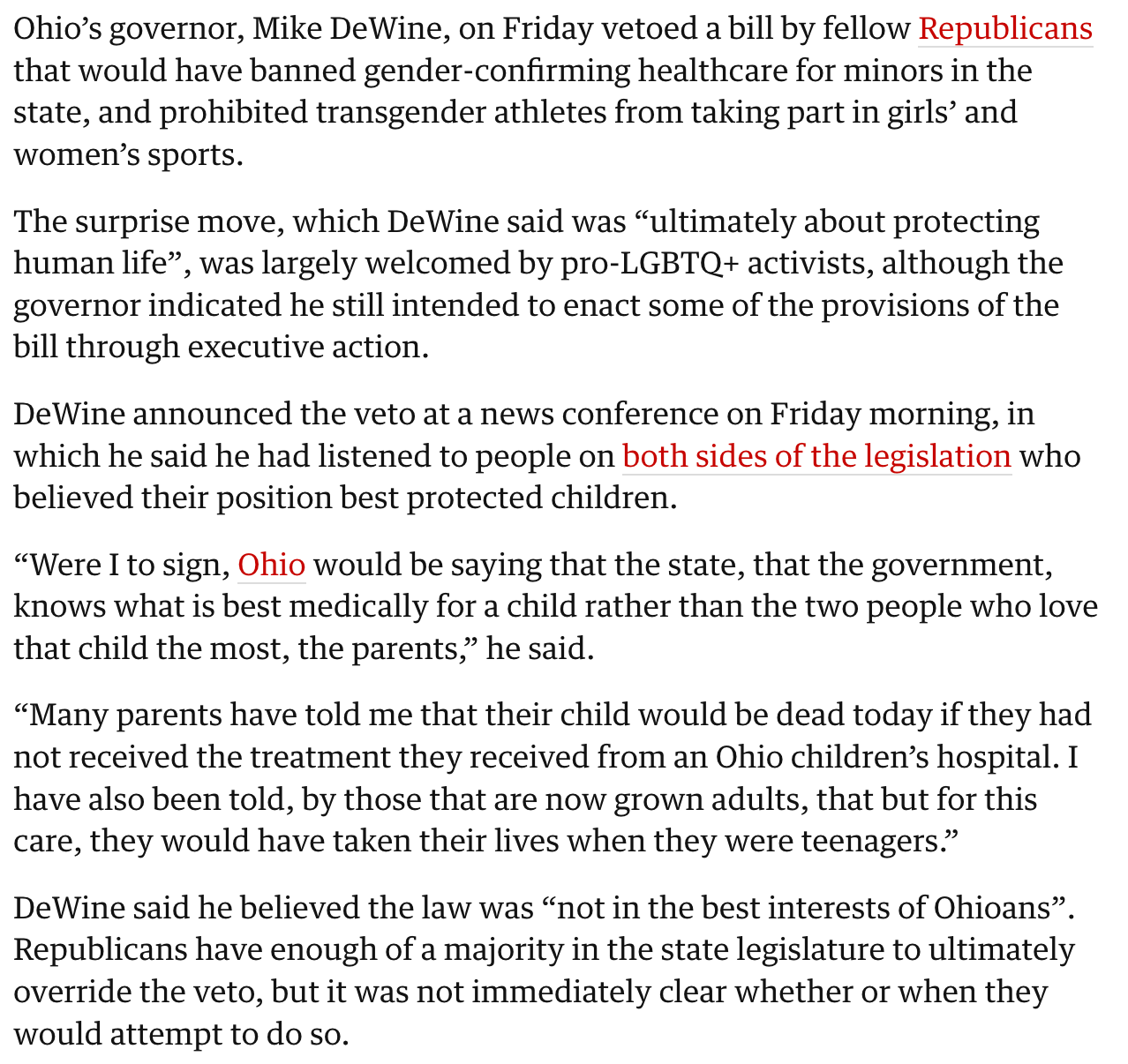

I hope they override it overwhelmingly. This is a betrayal of the interests of Ohioans, and a particularly symbolic betrayal by a longtime GOP figure. Ohio’s junior senator is not happy:

Far too often you can count on establishment Republicans to do the wrong thing, out of a desperate desire to be approved of by the Ruling Class. I loathe these politicians. Think about it: the Republican Governor of Ohio has concluded that families have the right to sexually mutilate, through chemicals and surgical procedures, their minor children, inflicting permanent damage on these children’s bodies.

If adults wished to make these interventions on themselves, I would still oppose it, but I would recognize that this was a categorically different matter. But these are children. We know from studies that the overwhelming majority of children with gender dysphoria resolve the dysphoria by the time they are 19 — most of them settle into a gay identity.

The Republican governor of Ohio cares more about appeasing some of the most destructive forces and people in our society, than he cares about protecting children from them. It’s scandalous. I hope the legislature massively overrides this veto, to avenge this betrayal.

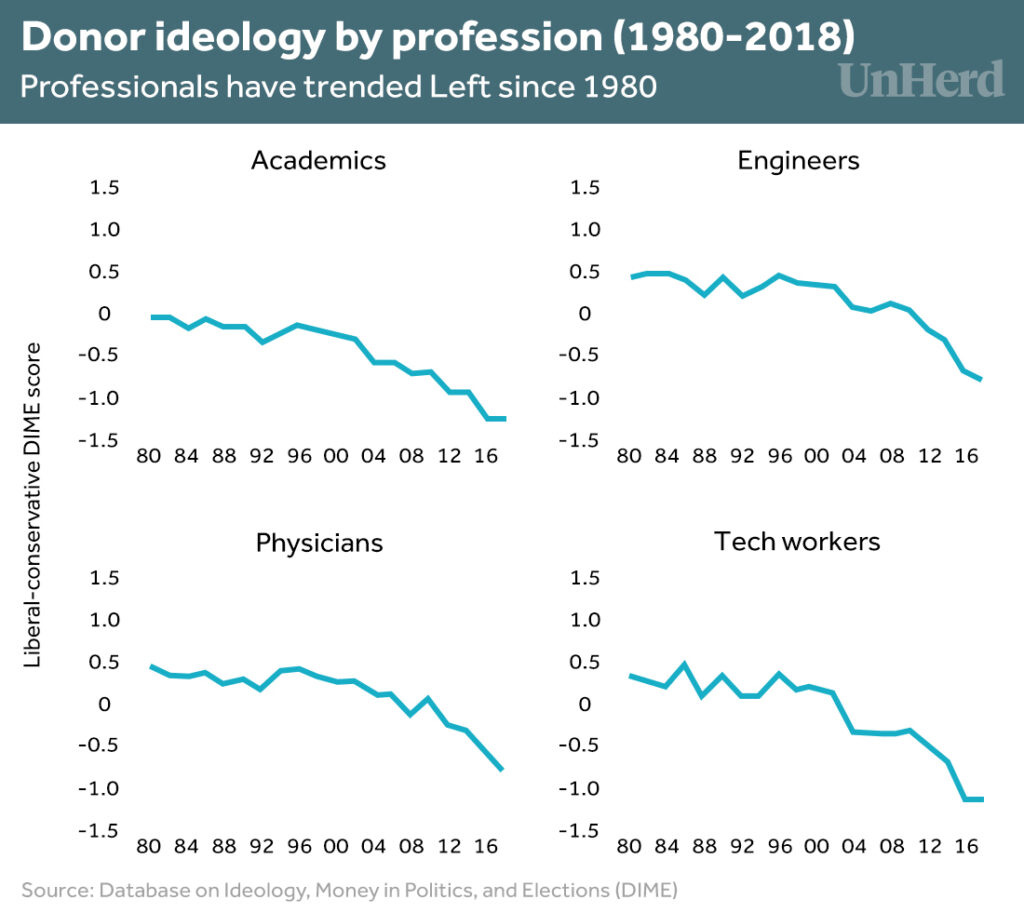

But look: there may be more to this than what’s obvious. Today in UnHerd, the social scientist Eric Kaufmann writes about how in recent years, people in the professions have moved left. Excerpt:

Why are conservatives disappearing from the professions? One explanation is that Left-modernist cultural sensibilities once confined to academics and bohemians have diffused more widely among the elite.

Academic Kevin Bass this week drew attention to the fact that just 3.4% of American journalists described themselves as Republican in 2022. Among academics, the figure was just 6%. Even among medics, nine in 10 political donations go to the Democrats.

The figure below examines trends within a broader range of American professions. Higher scores on the database‘s scoring system signify a pro-Republican bias, with lower ones revealing a Democratic tilt. Notice that professionals in almost all sectors, even engineers, now trend Democratic. The George W. Bush (post-2000) and Donald Trump (post-2016) eras were accelerants, but the trend is a steady one. While we don’t have similar data for the UK over time, the share of journalists and academics who lean Left in Canada and Britain is largely similar to the US.

These shifts reflect wider ideological changes among the highly-educated. The American National Election Study reveals little change in the political ideology of US university graduates between 1980 and 2000, then a shift from 41-26 conservative-over-liberal in 2000 to 40-33 liberal-over-conservative by 2020.

These changes occurred earlier and faster among Americans with a graduate degree (Masters or PhD). This group went from 40% liberal and 47% conservative in 1980 to a 35-28 liberal advantage in 2000 and then to a 46-31 liberal advantage by 2020. Data on first-year college students shows that the Leftward shift occurred entirely among women after 2004, with the gender gap growing steadily to 14 points by 2017. The entry of women into the professions thus accounts for some of the change.

The elites in American society are ever more cultural leftists. DeWine reads the tea leaves. His was a donor class move.

The New Old House

My mother alerts me that my childhood home has gone on the market. She sold it a couple of years ago before she moved into the care home, and the couple who bought it have now renovated it extensively, and put it on the market. Take a look here.

They’ve worked magic with this old 1969 ranch house. I hardly recognize it. There’s a part of me that feels that I should be somehow hurt by this — a silly thought, but you know how it goes with nostalgia. But I’m really not. Or am I?

Here is a passage from The Little Way of Ruthie Leming in which I anticipated this moment in my life:

Late on Thanksgiving afternoon, I left Mam and Paw’s to walk over to see the house spot. The cleared plot took in most of what had been Aunt Lois and Aunt Hilda’s orchard. Their cabin itself sat on land that belonged to cousins who lived far away, and with whom we didn’t get along. Standing where the new house would be, near a barbed wire fence marking the property line, I could faintly see the outline of the cabin through a thicket. I decided to take a look.

I crawled through the barbed wire, and navigated slowly through the overgrown brush. Brambles, briars, and overgrowth had consumed the camellia bushes Loisie had so carefully tended. The orchard and her gardens were a ruin, and so too, I now saw, was the old cabin, which predated the Civil War. I had not laid eyes on it since Loisie died and Aunt Hilda moved to a rest home some 15 years before. The front porch was so overgrown by bushes and vines that I couldn’t reach it. A tree had fallen on the roof over Loisie’s bedroom, on the downstairs level, cracking open a window frame. I climbed through.

Had the old house really been this tiny? Two wee bedrooms downstairs, a bathroom the size of a walk-in closet, and up a short staircase, a galley-like kitchen, a small pantry, a sitting room, and a library. The whole thing felt like a dollhouse, but in my memory, it was much larger. Then again, it would have appeared so to a small boy.

The cabin was vacant and musty, but it still held the faint aromas I remembered from my childhood. The damp charry clay smell from the fireplace. The cracked corn dust from the bin in the pantry where they’d kept bird feed. That peculiar scent of their enameled cast-iron wash basin in the kitchen. If I closed my eyes, I could recall absent smells: cut jonquils and paperwhites in a Mason jar; the Keri lotion Lois kept by her rocking chair to keep her hands moist; the nutty, buttery pecan cookies baking in the kitchen, or golden cupcakes from Loisie’s 3-2-1 recipe. I would sit on her lap at her table in the kitchen and stir the batter in her pale green 1940s Fire-King mixing bowl. Batter. Loisie taught me that word. I loved saying it, and licking the spoon when we were done mixing, feeling the grains of sugar with my tongue against the roof of my mouth.

There, as a grown man, I stood in the dark, cobwebbed kitchen, wondering where it all had gone. There, on a board above the washbasin that served as a shelf, sat a relic: — Loisie’s Fire-King mixing bowl. I held it in my hands, a totem of my youth. It had once seemed as big as a foot tub in my lap. In truth, it wasn’t much bigger than an oversized cereal bowl.

Something must have unnerved me, because I felt the strong urge to leave. I took the pale green bowl in hand, went down the back steps, and stood for a last minute in Loisie’s bedroom. It was the size of a monastic cell, and now bare. But look, there is where she kept her carved Honduran wooden bobblehead of a Carmen Miranda figure, head piled high with colorful tropical fruits, which delighted me as a boy. Tegucigalpa, the word that tasted like the juicy fruits on the dancer’s head. There was once a bed in that corner, where Loisie and I lay down late one night when I stayed over and read a Wisconsin cheese catalog, me enchanted by the brightly colored cellophane wrappers. What kind of place is this Wisconsin, where it snows, and the cheese comes wrapped like a Christmas tree ball?

Out those French doors was the pocket-sized side porch where I fed Loisie’s cats with her, and where, after she was taken to the hospital in her penultimate illness, a wicked cousin came one Sunday afternoon, lured all the cats out with their dinner, and killed as many as he could with a shotgun. The rest ran away, and lived wild in the woods. Hilda had asked the no-good cousin to get rid of the cats, because she was tired of caring for them for her sister. That’s what he did, gruesomely. My mother, my father, my sister and I sat in our backyard that day, hearing what was going on, crazy with grief, powerless to do anything to stop it.

When we saw the cousin’s truck leave, Mam hurried through the pecan orchard to the cabin, and ran to the side porch, where the cats were accustomed to getting their food. She saw spattered blood, empty shotgun shells, and saucers of milk. He must have taken the dead cats with him.

Lois died not long after that, never knowing what had happened to her cats. Before she died, I went to Aunt Hilda, and told her I knew what had happened, and that she had ordered it. “Darling, please don’t be angry,” she said, but I was, and told her I hated her, and ran home. After Loisie died, that side of the family dispatched Mossie to the nursing home and looted the cabin of all the art objects and relics of their lives. I visited Mossie a few times, but her mind was starting to go in a serious way, and given what had happened with the cats, my heart wasn’t in it. Mossie died in 1988. I didn’t go to her funeral because I was backpacking around Europe with a college buddy. In a way, that was the most fitting tribute I could have given to what her life meant to me.

As I stood there staring at the side porch where the cats had been killed, I thought about the sad, grotesque ending to my love affair with the old sisters, and that house. There were three worn wooden steps connecting the painted concrete slab to the kitchen. I sat on the bottom one as a small boy, while a young cat I called Stripey sat on the top step, licking my hair. One day Stripey followed me home, and Loisie told me I could keep him. Stripey was my first cat, the first pet I remember loving with all my heart. But now the old steps had collapsed, the woods was about to overtake the side porch, and the ghosts in that ruin were starting to unnerve me.

I put those thoughts out of my head, climbed back through the bedroom window, slogged through the thicket, squeezed between the barbed wire of the fence, and was once again in the sunlight. I looked across the yard at Mam and Paw’s brick house in the near distance, as the evening began to fall. Suddenly it struck me that one day, their house would be as Hilda and Lois’s cabin was today. I could hear people inside, our Thanksgiving guests, laughing and talking, but they would all be dead one day. Perhaps some great-grandchild yet unborn, or one of his children, would come in through a back window and search for relics of a barely remembered past. I tucked Loisie’s mixing bowl under my arm and walked on to the house.

Well, the modest red-brick ranch house has not fallen into ruin. To the contrary, the new owners made it beautiful. When they sell it, those new owners will have no memory of what it once was. What a strange thing to experience history as a personal emotional event. The reason I write about it again today (older readers will recall me citing this same passage when my mom sold the house last year) is because I’m reading now a marvelous new memoir by the historian Peter Brown, now in his eighties, who grew up as a Protestant in Dublin. In the book, he details the things that created in him a historical mind. In this excerpt, Brown reflects on the influence that two of his boarding school history teachers — Laurence LeQuesne and Thomas “Kek” McEachran — had on shaping his sensibility:

I suspect that what drew Laurence to Kek was a shared feeling that they both lived at a ninety-degree angle to the modern world. At a happy drinking party of fellow teachers at the Lion Inn at Shrewsbury, in later years, Laurence was somewhat surprised to find that

all four of us, at bottom, hate the present; is it typical of our age and class, or what? … what is it that makes [us] quarrel with the present?

What made Laurence’s quarrel with the present so distinctive was the intensity of his sense of the past. This was his most personal and decisive gift to me. It was not the same as reactionary conservatism; nor was it mere nostalgia. It involved a more acute and more tragic sense. The past was there, and it was not the present. It had once been as full of life, sound, and color, as much an arena of creativity and of human dignity, as the present. Now, like a treasure ship seen at the bottom of clear waters, it lay there, irrevocably trapped in time. Laurence’s hero, Thomas Carlyle, shared this feeling: “a quite exceptionally acute private awareness of the mysteriousness of time as the transparent medium in which all human activity is irretrievably stuck.”

I had a history teacher in high school — he reads this newsletter — who brought history vividly alive for me. I could never see history as a dull recitation of facts and events after his Russian history course. My son Matt has an undergraduate history degree, and will start graduate school in the next year or so; he is devoted to historical preservation, especially in museum archives. I don’t know why he is this way, because I don’t think we ever had a big conversation about it. He did spend much of his childhood immersing himself in the history of both the US and the Soviet space programs. For a significant chunk of his young life, what the Russians and the Americans did in the quest for space was more real to him than the world that kid lived in, I think.

When he turned 14, I took him to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory on a tour, as the guest of Keith Comeaux, a college classmate of mine who was (is) director of the Mars Rover mission. It knocked me flat to listen to that boy talk at a very high level with Dr. Comeaux about the history of JPL and NASA. It was like watching wizardry in action: by the accumulation of details, linked together with purpose, Matt conjured up a lost world. He is a natural historian.

One more bit from Peter Brown:

History, for me, has always been something more than a discipline — more than a set of problems to be solved, a narrative to be put together from bits and pieces of evidence about the past. It is, rather, a perpetual awareness of living beside an immense, strange country whose customs must be treated by the traveler from the present with respect, as often very different from our own; and whose aspirations, fears, and certitudes, though they may seem alien to us and to have turned pale with the passing of time, must be treated as having once run in the veins of men and women in the past with all the energy of living flesh and blood. I learned from Laurence that the aim of the historian was not simply to argue about the past; it was to bring that past alive — to recover a lost world.

Now that I can see my sixtieth year on the distant horizon, reflecting on my personal history has taught me that the most primitive driving force in my own life has been a search for Home, but a Home that never existed. I wanted to merge the red-brick ranch house with the antebellum cabin. I loved much about my actual home (the ranch house), but I felt safest and most alive in my aunties’ cabin. Why? Because it was there that I first learned that we lived in a world of wonders. Those old women knew that I was a bright, strange boy, and unlike my father, did not try to muscle the strangeness out of me, but rather encouraged and channeled it. Yet my father was a good man who was both strong and tender with us kids, and, let’s face it, was more realistic than my intellectual and aesthetically inclined aunts (here’s how old Lois and Hilda were: they were the aunts of my father’s mother; their own father was a Civil War veteran).

I lived my emotional and imaginative life as a child in the five-minute walk between the red-brick house and the wooden cabin. It was so safe and idyllic in my early Seventies childhood that my mom can recall giving me a couple of fresh diapers to carry with my books under my arm, and seeing me off as I walked through the pecan orchard to Lois and Hilda’s to spend the day. Can you imagine? I can.

How tragic life is! I mean tragic in the philosophical sense: the realization that no matter how hard one works, and how brilliantly one plans, life, ultimately, cannot be controlled or perfected. To have a tragic sense of life is to live with an awareness of time’s meaning. But tragedy also requires wisdom, or even pleasure, to emerge from suffering. In a way, my writing in this space, and in my books, is all part of a deep emotional need to find meaning in events, and especially to pull redemption out of the ruins.

Loisie’s pale green Fire-King mixing bowl sits in a storage facility in Baton Rouge. Next time I head over there, I’m going to bring it back. It is the totem that explains me. It is the condensed symbol of my way of seeing the world.

And yet, when I am gone, it will be just a bowl. Whichever one of my kids inherits it may remember that oh yeah, this meant something to Dad — something about Aunt Lois. But that too will fade. All that will remain is bowl-shaped glass, as meaningless to the people of the future as the red-brick ranch house — now painted white — will mean to the people who buy it, and who will move in having no memory of what it looked like before, and of the people who lived there and, in my father’s case, died there.

This is why life is tragic, inescapably so. But that also gives life its sweetness, does it not? It is always passing. Last time I was in West Feliciana, my cousins, who are older than I am, were telling me about how when they were kids, they would visit our grandparents in their little house on the top of the hill, and overhear the old folks talking endlessly about the Civil War, which was by then a century in the past. Those days were more full of life to the old folks on the front porch than the days in which they lived. Now that I am on the cusp of becoming an old folk myself, this is starting to make sense to me.

My oldest friend in the world was the last of eight kids, I think. Their father, now long dead, had been a bombardier in the Second World War. He came back to Louisiana and became a house painter. My friend spent summers in his youth on long car rides with his dad to reunions of the bomber squadron. At some point, it struck my friend that life had never been more vivid and meaningful to his father than those years he spent saving civilization from the Nazis. His father, the house painter, lived all his days on those memories.

And you will recall that we only discovered that our neighbor Merriell Shelton, a modest, quiet, intense air conditioner repairman who lived with his wife and sons in a tiny brick house on Highway 61, had been the great and terrible warrior Snafu from the Pacific theater. He was immortalized in his comrade Eugene Sledge’s memoir, With The Old Breed, and in the television series The Pacific. Snafu’s neighbors only discovered this by reading Sledge’s history. Ol’ Merriell, who kept to himself, was just a glass bowl to us, if you take my meaning.

Funny: in the living room ceiling of the red-brick (now white) house where I grew up, there is a scar that no number of paint jobs could obscure. Daddy explained to us kids that that’s where Merriell Shelton stepped through the ceiling when he was installing the air-conditioning ducts. Unless they read this, the people who live in that house now, and the people who will live in it in the future, will never know that they live with evidence of the breaking-through of history into their living room.

Man, I tell you: we don’t value history enough. Not the bullshit history they teach in the universities today — as the gathering of evil deeds marshaled as part of the case against our ancestors — but as a thrilling and tragic story of who we were and who (therefore) we are. Anyway, I’m going to post this and go back to my cozy room here in Cambridge and spend the rest of the afternoon communing with Peter Brown.

Rod, I am a long time reader of yours, a therapist in Raleigh, married to a guy in the ministry. I’ve moved in many Protestant circles, as well as the parachurch world for years. I have followed the anguish of your marriage loss and felt that with you. What I have wanted to say to you is that, over and over again, a place of unjust suffering seems to accompany the life of someone who has enormous Kingdom impact. It’s uncanny to me, as a person who has heard a thousand stories by now. It brings to mind, often, the old expression—the devil takes his pound of flesh. I know that doesn’t compensate for lost family—but it does bring a measure of comfort, in that Life is being poured out in a thousand places through a wound that should have never happened in your life. In the unseen world, you are clearly “disturbing the universe,” to borrow T.S. Eliot’s words. I pray for you often, as my brother who is shaking things up :)

"His was a donor class move."

It absolutely was, but therein lies a problem we don't talk about much but looms large over this landscape.

Campaign cash makes the world go round - gets pols elected and re-elected. Yes, the donor class trends left and will continue to do so - the more people seek out higher education, the bigger the "credentialed class," and that class prides itself on being not just smarter than than the short-fingered vulgarian class, but more virtuous. Cutting the breasts off a psychologically confused teenaged girl is seen as the moral thing to do, increasingly, by those who have the most money to give.

Those who oppose such things tend to have less money. They may constitute an outright majority of the population (not sure about that, but maybe); but if they're not giving campaign cash, their voice matters less; they are yappy plebs to be kept at bay while the REAL work of the GOP, doling out tax breaks and other favors to the special interests, takes precedence.

When the people with the money who give the money favor wokism, how are those who don't have the money and don't give the money to resist?