Hanania's Shocking/Not-Shocking Exposure

And: Is megachurch pastor J.D. Greear right about leaving church early?

I was shocked, but not really, when the prominent right-wing Internet personality Richard Hanania was revealed yesterday to have posted white supremacist material for years, under a pseudonym. Shocked, because the things he is alleged to have written are evil. (“Alleged” because he has not, as of this writing, denied it, but the sleuthing seems to have nailed him hard.) Not shocked, because though Hanania allegedly wrote these things, he has written enough under his own name to indicate a certain sympathy for the evil stuff.

I’ve found him to be someone who says interesting things from time to time, but I have been very wary of him because he had more than a whiff of the eugenicist about him. He hates Christianity in a Nietzschean way, as Matt Schmitz pointed out yesterday; “Richard Hoste” was reportedly Hanania’s pen name:

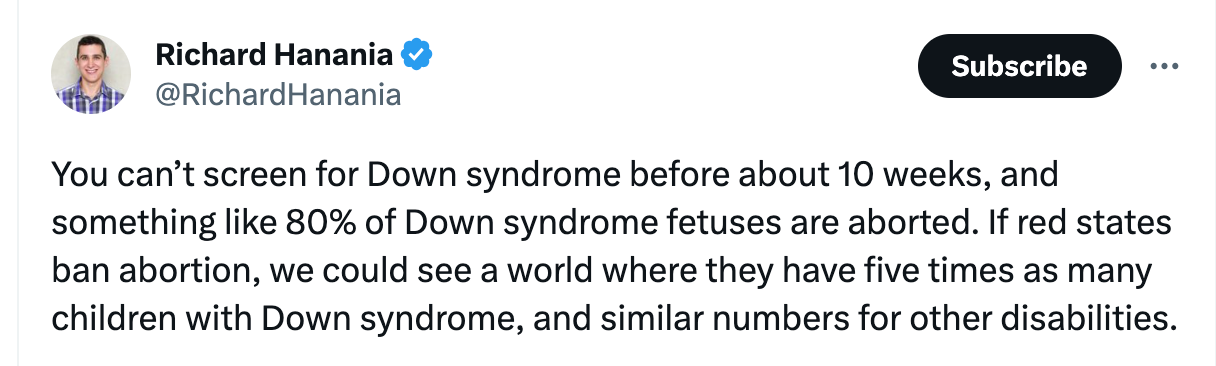

Under his own name, Hanania has called on the old to kill themselves for the greater good of society. And for using abortion as a means of eugenics:

If you go look at Hanania’s Twitter timeline, you’ll see that most of what he tweets is not like this. At times he says intelligent things that make you think. People who aren’t familiar with his writing might believe that people on the Right knew he was really a white supremacist eugenicist, and embraced him anyway. Not true. Like I said, I’m (sadly) not surprised to read about the things the guy wrote earlier in his life, under a fake name, and I’m grateful that he has been exposed.

But I believe it’s important to be generally tolerant of intellectuals who may hold some immoral views, but who also can be penetrating thinkers whose insights are worth considering. It’s why I have always stuck by Andrew Sullivan, though I think he is seriously wrong about a very important moral issue. And it’s why I hope that some of the people on the Left who follow me stick with me, though they radically disagree with me on some things. At the top of this post, I put a photo of a recent podcast in which the socialist intellectual Freddie de Boer interacted with Hanania. He really is a compelling figure (Hanania), with whom even brilliant mavericks of the Left, like Freddie, engage. What’s wrong with that?

I think it’s a bad habit to cancel people for transgressing narrowly drawn boundaries. A Dutch intellectual I know told me that it’s hard to overstate how intellectually conformist Dutch society is. For all its pretense to being freethinking, he said, Dutch intellectuals can only bear to hear opinions within a small range of deviation. Anything outside of it makes them very, very nervous. As a scholar who has spent most of his professional life outside of the Netherlands, it frustrates him to deal with the intellectual constraints of Dutch society.

Now that I know more about Hanania, I think that absent public and meaningful repentance, he completely disqualifies himself as a serious thinker. I don’t care how smart he is, or how interesting his views on this or that may be. He is — if he has not abandoned his older views — a stone-cold racist. I wouldn’t tolerate the same sort of views in, say, a non-white intellectual, and I’m not going to tolerate them from Hanania. Some lines must not be crossed. Because I don’t follow him closely — I was surprised to discover that I follow him on Twitter; his stuff only ever appears in my feed when someone else tweets it — I didn’t realize that he had made those remarks I cite above, though I’ve seen similar things from him. I expect that his forthcoming book will be cancelled in light of the new information (and you really have to read the link in the first graf to read how awful they were).

Again, if Hanania were to convincingly denounce his past views, he could be rehabilitated. I’m a Christian, and I believe in forgiveness and second chances for those who genuinely repent. But it will be very hard for him to pull that off, considering how close his current opinions track with his forbidden ones.

Again, though, if you want to know why it is that Hanania attracted the favorable attention of more prominent intellectuals and conservative figures, and has been considered a reasonable interlocutor by left-wing intellectuals like Freddie, you have to understand that he is a weird, hard-to-pigeonhole guy who is half-crazy and half-brilliant. Here he is explaining how he does what he does. Excerpt:

People often ask if I have any tips on how to be a successful writer. Of course! Just do the following, and you can follow my path:

Write about how wokeness is a cancer. Then, when you’ve built an audience of right-wing anti-wokes and MAGAs, make sure to release a series of articles about how conservatives are immoral and have low IQs, liberals are completely right about January 6, and the media is honest and good.

Have a vicious hatred of masking. But when that gives you fans that are anti-vaxx too, constantly tell them they’re stupid, you hate them, and they’re the reason we can’t have nice things.

Write a report about how China is going to become the strongest country in the world, and an essay arguing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will usher in a new era of multipolarity. Stick to this view throughout February 2022, and defend Putin’s position in the face of all of Twitter having erupted in moral outrage at what he has done. Become known for that. Later that year, declare you hate Putin, that China and Russia both suck, and America will lead the world indefinitely. Keep talking about Asians and their love of masking, explaining how this represents a great moral and spiritual defect and tying it into your geopolitical analysis.

If you’ve got any right-wing fans left, make sure they know you have positions on abortion and euthanasia that would be too much even for most liberal Democrats. As everyone is flipping out about the Canadian MAID program, write about how it doesn’t go far enough and killing yourself is actually masculine and honorable, and you are repulsed by any moral system that holds otherwise, which is for the weak.

For good measure, throw in some takes about how it doesn’t matter if female teachers have sex with underage male students, and argue that Harvey Weinstein is a political prisoner.

Do all this, and you will become an extremely popular writer beloved by the world.

Or maybe not. What I hope is clear is that there really wasn’t a plan here.

It is, however, an interesting question: at what point does an intellectual go from

You see? He’s very hard to pin down. Almost everybody can find a Richard Hanania they love, and a Richard Hanania they hate. It’s what makes him interesting. I don’t want to read intellectuals of Left, Right, or center who reinforce what I already believe. Hanania is at times infuriating, but never boring. That said, the pseudonymous material that the investigation uncovered is sickening, and nothing smart he has to say about anything else can overcome that stigma, at least to my mind.

My basic orientation is to try to be as generous to an intellectual as I can, bearing in mind that they might be the victim of bad-faith press. As I wrote here this week, it was enlightening to me to read the writings of Renaud Camus, the French intellectual who came up with the idea of the “Great Replacement,” and to discover that whatever some neofascists or anti-Semites might believe, Camus himself does not believe that this is the result of a sinister cabal of elitists who came together to get rid of white people. Camus is describing instead an emergent phenomenon in France (and Europe more broadly), as the second half of the 20th century brought mass Third World migration into Europe.

Because I had only read about Camus, I took for granted the media’s portrayal of him as a far-right white supremacist. In fact, he’s a left-wing gay atheist who happens to value his ancestral culture, and who laments its steady erosion and disappearance in the globalized world — aided and abetted by numerous forces: capitalism, liberalism, multiculturalism, and so forth. More to the point, Camus observes (borrowing an idea from his friend, the Jewish intellectual Alain Finkielkraut), that the “Great Replacement” progresses in part because nobody is allowed to talk about its various manifestations without being smeared as a fellow traveler of Hitler. Thus do French people — especially Jews, gays, and others who are particularly hated by the migrants, most of whom are Islamic — find themselves forced to acquiesce in the decline of the culture that defines them as a people.

I should have been aware that Camus was being slandered by liberal media, but how was I to know until I read him myself? An intellectual friend who also knows Camus affirms that Camus doesn’t believe in “Great Replacement theory” — that is, a conscious plan to replace Europeans — but rather sees it as an empirical observation of what’s happening in France. Says my friend: “All the difference between racist ignominy and responsible cultural criticism lies in this little distinction. Because once you believe in a conspiracy, then you believe in conspirators, hidden enemies, deceitful Jews, etc., and we’re on the road to hell.”

Very true. I bring it up here just to remind you that we should be careful not to accept without skepticism what the media say about a particular intellectual. If you are just now coming to Hanania from the exposé, or by reading people saying “I told you so” about him, you would never guess why Hanania, who has a PhD from UCLA, managed to get so far as a mainstream intellectual. The economist Bryan Caplan once summed up Hanania’s appeal well: [“W]hat’s most impressive about Hanania is the absence of Social Desirability Bias. He describes the world as it is, and offers advice to improve upon the ugly world in which we find ourselves.” I’ve never read whether or not Hanania is on the autism spectrum, but it seems clear to me that he very much is, and that this has something to do with his intellectual style, and the substance of his writing. He lacks the inner sense that tells him, “You shouldn’t go there.”

That’s probably it for Hanania’s career. I do hope that someone can get to him, truly convince him of the evil of the things he once believed, and maybe still does, and lead him to (moral or religious) conversion and honest, non-instrumental repentance. One thing I hate about our intellectual culture is that there is endless forgiveness and rationalization around left-wing intellectuals who believe monstrous things, and who aren’t sorry about it. Consider Angela Davis, one-time recipient of the Lenin Peace Prize, and unrepentant defender of gulags. (Of Czech political prisoners, she sneered, “They deserve what they get. Let them remain in prison.”). They still consider her a hero on the Left. There are many more examples. But we can’t let whataboutism stop us from living out moral hygiene on the Right. I strongly object to the “No Enemies To The Right” line. That way is a rationalization for evil.

So, back to the question: How do we determine when an intellectual or an artist, whatever his or her views, has crossed a line such that they cannot be part of the broad conversation?

One last thing about Hanania: he is a great example of what Ross Douthat meant ages ago, when he said to liberals, “If you don’t like the Religious Right, wait till you see the Post-Religious Right.” If you haven’t yet read Tom Holland’s great popular history Dominion, you really should. Holland is not a believing Christian (though I understand that he sometimes attends church), and is best known as a historian of the Classical world. In Dominion, he writes about the genesis of that book as his wondering why it was that ancient Rome, which he loves as a historian, was such a cruel and morally repulsive society, and how it was that the things he valued as a secular liberal humanist came to dominate a world that 2,000 years ago, lived by Roman values. The answer, he found, was Christianity. Dominion tells the story of the great transformation Christianity made on Western culture.

Christianity did not re-create the Garden of Eden. But it did, over time, moderate the worst passions in our hearts, and cultivate virtues unknown to Roman pagan society. This is not even arguable. Read Tom Holland if you doubt it. If you want to see what a world without Christianity can look like, Nazism and Communism give you two strong examples. We are now well on our way in the West to cleansing the residual Christianity from our cultural memory and practice. We are re-paganizing. You should prepare yourself for many more Hananias. They are not a bug of the system now emerging, but a feature.

At Church, When Is It OK To Show Up Late Or Leave Early?

I couldn’t get the name of the Twitter account that featured this into my screenshot, but its name is “Smash Baals” — and here is the link to watch the very short clip he describes:

The pastor here, J.D. Greear, is the former head of the Southern Baptist Convention. You might remember his name as the pastor who led the prominent academic Molly Worthen to Christ. I remind you of that, because Greear has been getting dunked hard for this clip.

I too think it’s pretty funny that he faults his congregation for treating church like a religious show, when everything about the service is designed to make it appear like entertainment — right down to the staging as entertainment. I wonder if Christians who have only ever gone to these modern megachurches realize how their “liturgies” look to Christians who attend more traditional churches. To say they have been shaped strongly by the values of entertainment is not to criticize, but to state an empirical reality. How can you complain that people treat church like a show when you have given them all kinds of visual and aural clues that that is exactly what it is?

The contrast is strongest with traditional Protestant services, which resemble lectures with breaks for singing, but worship services in much of Catholicism and all of Orthodoxy could also be described as a religious show, of sorts. Here in Budapest, there are no English language Orthodox liturgies, which really serves to highlight the “show” aspect of the Divine Liturgy for people like me, who don’t understand the language in which it is being celebrated (in this city, that’s Church Slavonic, Serbian, Hungarian, or Greek). I think the pageantry is necessary. You’ll recall my frequent citing of the late Cambridge scholar Paul Connerton, who found in his anthropological work that communities that celebrated their sacred story in unchanging rituals that involve using the body are more successful at retaining those sacred stories under the pressures of modernity.

Besides which, for Orthodox and Catholics, at least, the liturgy has come down to us from the first centuries of the Church, and must remain largely untouched. Since the 1960s, Catholics of the Roman rite have radically changed their liturgy, in ways that are unthinkable to the Eastern mind (even the minds of Eastern Rite Catholics, who use the same liturgy as the Orthodox — the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. The “Novus Ordo” — the new mass created by the Second Vatican Council — strips the mass of a great deal of its pageantry. To say that the Catholic reformers “Protestantized” the mass is not an insult, but a mere description — except the Anglicans, who are Protestant, mostly have a “higher” liturgy than Novus Ordo Catholic parishes. Note well that we are not talking about the Eucharistic validity of a liturgy, only its aesthetic qualities.

The point is, I’m not in a position to fault other Christian communions for making their worship a performance. The important question is: what does the performance do to, and for, the people who observe it? In Orthodoxy, no one is an outside observer; you are expected to participate, with your prayers, your bows, your prostrations, and, of course, by taking communion. The celebrant (the priest) is not a performer in the secular sense. He disappears within the liturgy. His only role is to faithfully say the words and make the gestures. The “show,” then, is first of all about offering right worship to God, and second to be brought into communion with him, both in our souls during the act of worship, and then literally, in the taking of the Eucharist. In other words, the goal is not to entertain one, or to give you the kind of delight you get when you go to a concert or a movie. The goal is to shape your soul through ritual practice.

Is that what these megachurch liturgies do? I’m not asking rhetorically. I’ve never been to one. If they are, then what form do they seek?

A lot of people have been bashing Greear for shaming people who show up late and leave early. I understand Greear’s complaint, and think he has a point. On the other hand, when my kids were younger, it was difficult to get to church on time, every week. Every family with little kids knows this. And sometimes, we would have to leave early, if the kids were acting up. One thing unique to Orthodoxy is that the liturgy is more like a bonfire gathering than a set performance. Traditional Orthodox churches don’t have pews, which only came into being in Western churches with the Reformation; all the pre-modern European cathedrals were built for standing worship. It is considered a normal thing for people to wander the church during liturgy, lighting candles, venerating icons, offering private prayers, and the like. This is a great thing when you have a crying baby or a little kid who is being bumptious on a particular Sunday. You can take the child outside until they calm down, and nobody notices, because you don’t have to crawl over a bunch of people in the pews.

Orthodox people have a reputation for coming to church late. Not all of us, but it happens a lot more than I saw in Catholic or Protestant services. I think the fact that you can slide into the liturgy without people noticing encourages that. It’s a bad habit, but always a temptation.

Sometimes, one leaves early, right after communion instead of waiting for the service to end. Last Sunday I left right after communion, but before the liturgy ended, and made a beeline for a coffee shop. Why? I usually go to an early liturgy, but that day I went to the ten o’clock one. That put finishing time around 11:30. If you are as much of a caffeine addict as I am, you will not be surprised that the violent thunderstorm that is a caffeine headache was starting to build in my head. (Orthodox are expected to fast from food and liquid that’s not water before communion.) A caffeine headache can only be ridden out: no pain reliever does much good, and though drinking coffee stops it from getting worse, you are stuck with it all day long. You can say it’s a silly reason for leaving church early, but then, you aren’t the one who has to deal with a serious headache for the rest of the day.

Besides which, in this particular service, the sermon came at the end, after Communion — as opposed to inside the service, which is more normal. I couldn’t have understood a word of it. The prospect of waiting around and surrendering to a headache, while the priest preached a homily in a foreign tongue, was unappealing to me. So I bolted. Kill me now.

My attitude about sticking around after church changed 100 percent when I left Catholicism for Orthodoxy. Growing up in the Methodist church, and only being a sometime churchgoer, I never saw people sticking around for coffee hour after church. It just wasn’t something our congregation did back in the day. When I became Catholic, after church, everybody went home. Maybe some parishes did a coffee hour, but no parish I was ever part of did. I thought that was normal. When she converted to Catholicism, my wife found this very hard to get used to. She had been raised Southern Baptist, but was worshiping in a Reformed (PCA) congregation when we met. Coffee hour was normal to her. How else were people at church supposed to get to know each other?

At the peak of my (our, really) crisis of the Catholic faith, when we first attended an Orthodox liturgy, we were urged by parishioners to go to the coffee hour afterward. I wanted to go home, not only because I felt guilty going to a non-Catholic service, but also because — how to put this? — I didn’t want to be social. Nothing in my experience said that that’s what one did after church. It felt weird.

In fact, it was a wonderful thing. We stayed, like most people, for an hour and a half, meeting folks, eating, drinking coffee, having a good time. One the way home, my wife said to me, “Now that’s having church. That’s how I was raised.” I saw the appeal. I never would have imagined that coffee hour would have come to mean something to me, but it was vital in forming the sense that you are part of a worshiping community, not just someone who shows up at the Sacrament Factory to do your weekly duty, and go home. When we eventually decided to become Orthodox, the unofficial liturgy of coffee hour played an evangelical role. My wife was right, in a way that my hard-line left-brained way of thinking about church did not see: Orthodox coffee hour really was part of the experience of being formed as a Christian not just in your thinking, but in your way of life. Nobody makes you go to coffee hour, and you certainly aren’t sinning if you don’t go, but it’s pretty great. If you don’t show up, people assume that you had somewhere else to get to, or you weren’t feeling well, or the kids were having problems, etc. But if you don’t show up twice in a row, people will call to check on you. That matters. Christian worship is not supposed to be a bespoke, individualized experience. Without meaning to, I had let it become that with me. I needed coffee hour to bring me out of my own head.

I think this is what J.D. Greear is getting at. It’s an important point, and I hope it doesn’t get lost in the pile-on. I hate too that he’s being piled on, because as absurd as it is for a megachurch pastor to gripe about people treating services as a “religious show” as he stands in what looks like the stage of the Ed Sullivan Theater, the man raises some important issues.

I’m eager to hear what you have to say.

I’ve sent this missive out to the entire list, which is five times bigger than the paid subscriber list. Won’t you consider becoming a paid subscriber? It’s only five dollars per month, or fifty dollars per year, and you get at least one post every weekday, and sometimes more (like this one). We have a great comments section too — but only paid subscribers can comment. This Substack is the first comments section I’ve ever had in which I never have to moderate. It turns out when people have to pay for a product — even something as negligible as twenty cents per day — they are disinclined to treat it like garbage. Unlike every other comments section I’ve had, when you post something, it goes up without moderation. I’d say that’s worth something.

I read the Hanania post that Rod linked to and a couple of other pieces, and it’s clear to me that Hanania’s biggest problem is that he’s an asshole.

His views on Down Syndrome remind me of how the topic of DS brings out the worst in so many people. Many years ago Rod posted a story on his TAC blog about a high school that voted a young lady with DS as their homecoming queen. The comments section was riddled with indignation that a group of high school students treated a person with a disability as an equal. One commenter kept concern-trolling that the beautiful people were cheated out of their due, and oh the humanity!

It also astounds me that calling for mass abortion of “defective” spawn doesn’t disqualify someone from being a public “intellectual”, but racism does. To me, prejudice against people with disabilities and prejudice against people of different skin colors come from the same fetid moral sewer.

Would it be a good idea to send two separate posts when dealing with two completely separate topics--like today's Hananian/Hoste and church etiquette? Having two entirely unrelated topics in one post makes the comment section feel schizophrenic.