This week I finished reading Sigrid Undset’s Nobel Prize-winning trilogy, Kristin Lavransdatter. I’ve had the novels since a Norwegian friend gave them to me for Christmas 1992, but I’ve never been able to read them. The standard English translation, which has been around since the 1920s, is quite fusty. In 1997, Tiina Nunnally came out with a more modern translation, one that is said to be more faithful to Undset’s prose. All I can tell you is that it is a pleasure to read, and the other one is not.

And what a pleasure it is! The novel spans the 14th-century life of its title character, the daughter of a prosperous farmer in Norway, from age seven until her death as an old woman. All of life is in this book. Kristin is headstrong, daring, passionate, pious, and at times exasperating. Her marriage is tumultuous, with political intrigue changing the destiny of her family (and with numerous boys, it’s quite a family). She knows wealth, she knows poverty. She behaves nobly, and also selfishly, but always like a flesh and blood woman. This is one of those books where you fall asleep thinking about the characters and their dramas, and wake up doing so as well.

In 2017, the journalist Ruth Graham published a Slate essay in which she said (quite rightly) that somebody should make a miniseries out of Kristin Lavransdatter. Graham wrote, in part:

It would be criminally simplistic to describe the series as “conservative,” but there’s a reason it appeals so powerfully to a certain kind of bookish Christian reader. As flawed as Kristin is—she is proud, lustful, brooding, and fails to live up to her own moral standards—she is a devout believer, and the books are intimately concerned with her relationship with God. Undset was a Catholic convert, and one of the most remarkable things about the trilogy is that it’s a rare literary depiction of religious people that is both empathetic and unsentimental.

Early in the first book, Kristin’s angelic younger sister is gravely injured in a freak accident caused by a large ox. When the family realizes that the injury is permanent, they propose that Kristin enter a convent, as a kind of holy bargaining chip. She balks at this plan:

She resisted the idea that God would perform a miracle for Ulvhild if she became a nun. … She had the feeling that it was as Brother Edvin had said—that if someone had enough faith, then he could indeed work miracles. But she did not want that kind of faith; she did not love God and His Mother and the saints in that way. She would never love them in that way. She loved the world and longed for the world.

That internal battle between piety and hunger, between heaven and earth, echoes throughout the next 1,000 pages. Reading Kristin Lavransdatter made me realize how rarely I’ve encountered a serious 20th- or 21st-century novel that recognizes that “following your heart” might not be the key to happiness or goodness. The annals of historical fiction are filled with headstrong heroines who struggle between their own desires and the strictures of their fuddy-duddy communities, of course. But the revelatory thing about Undset’s approach is that it does not presume the community is wrong.

This is insightful and true. I can’t think of a novel that is as profoundly Christian as this one, in that Christianity is woven into every aspect of the character’s lives, as it really was in medieval Europe. Undset writes in great detail about churches, convents, and rituals, but it is all with an eye for enchantment. Undset was not yet a Catholic when she wrote this novel, but she was an excellent medievalist, and captures with unusual power the feeling of life lived in that age. She writes dazzlingly well about the natural world too, leaving the reader with a sense that Kristin’s world is bursting with — how to put this? — with meaning. And, she’s a wonderful storyteller, creating so many intense, beautiful, and at times heartbreaking moments. Anyone who has lived through marriage and parenthood will have many opportunities in this novel to shake their head and say, “Yes, that’s exactly how it is.”

But it’s also different. Kristin and her family are pre-modern people. They live in what you can rightly call the Age of Faith. Good and Evil are woven into daily life, certainly, but they are expressed much more vividly than they seem to be in our buffered era. The stakes for human conduct are much higher. If the crops fail, people might starve. If beggars turn up at your door, you have to feed them out of Christian charity, or you condemn them to a miserable death. A minor cut could become infected, and cut down a man’s life in his prime. The marriage a son or daughter makes determines in a dramatic way the fortunes of their entire clans, in a society in which extended families matter greatly. You see that kinship bonds serve as a kind of safety net for individuals in a harsh and unforgiving landscape. Undset is particularly good describing the rank smells of the period, especially of the poor, who bathed rarely, but also evoking strong sensual pleasure in the burning of frankincense in church, and of juniper branches in the home. Enchanting though the narrative may be, it is not romantic. This is Tolkien without Elven magic. It is thoroughly immersive.

Back in January 1994, I was on a trip to Norway for work. In Oslo, I went to mass at the Catholic cathedral, and was taken by the priest into the church’s treasury, and shown its relic of St. Olav, the 11th century king whose shrine was long at the Nidaros cathedral in Trondheim. This is the only known relic of the saint in existence, his shrine at Nidaros having been destroyed in the Reformation. Though it is kept in a silver arm reliquary, it is actually a leg bone. The priest bent back the silver hand and let me see a cross section of the actual bone, which testing showed is of a man who lived circa 1030, and who died in battle — both of which match it with St. Olav.

It was a stunning moment. There he was, the last of the great warrior and patron saint of the nation. I was not prepared for the significance of what I was looking at. Reading Kristin Lavransdatter, I learned that the people of medieval Norway prayed to him constantly, as a kind of father to the nation.

Later in the journey, I took a morning train from Lillehammer to Trondheim. Though it was an eight a.m. train, we spent the first hour and a half of the journey in the dark. At that time of the year so far north, the sun doesn’t rise till much later. North of Lillehammer we passed through long, snow-covered valleys, where you could see in the distance tiny pricks of lights, clustered against the blue-white blanket. These were houses. So thick and overwhelming was the snow that I found it hard to imagine anyone living there in such isolation. Then it occurred to me that there must have been people living there for a thousand years or longer.

Well, it turns out that this valley is where the people of Kristin Lavransdatter lived. As I read the novel, I recalled how overwhelming the snowfall appeared to my eyes, and how difficult it was for me to imagine people living in it in the late 20th century, with electricity, motor vehicles, snowplows, and the rest. The medieval Norwegians did so without any of that. Having seen what winter in Norway is like — I once bought a bottle of diet Coke at a convenience store in Oslo, then walked across the street to catch a tram; the soda was turning to slush in the bottle before the tram arrived — I was better able to appreciate how great was the endurance ordinary Norsemen had to show every single winter’s day.

In Trondheim, I was walking late one night with a man named Ulf Risnes, the singer of a Norwegian pop band, whom I’d met at a party. He put a dip of snus tobacco in his upper lip, as is the style there, to fortify himself against the snow outside, and took me for a walk downtown. We passed the medieval Nidaros cathedral in snow blowing so hard it stung my face like wintry wasps. I asked him if we could stop to behold it. It was like a carved mountain in the middle of the city, so dramatic in the biting snow. It looked like something out of Tolkien.

“We should give it back to the Catholics,” Ulf said, referring to the Reformation-era seizure of the cathedral. “We’re not using it anymore.”

Once again, I had no real idea of what I was seeing. This, the Nidaros cathedral, had been the final destination for countless medieval pilgrims. Kristin made this pilgrimage several times. One of the most memorable scenes in the novel is when Kristin, a young mother, and nearly crushed by guilt over something she had done, makes her way with her baby into the dark cathedral to pray, and there finds mercy. You don’t have to be a Christian to appreciate the psychological power of that moment, but if you are a believer, the scene will nearly bring you to tears. It is a strange and wonderful feeling to be immersed in a world where the presence of God is so keenly felt in everyday life. And, as Ruth Graham indicates, Undset has written a novel in which this plain fact of medieval life comes alive in an entirely unsentimental way. This is a book about truly pious people, but it is not a pious book. Medieval Norway was a violent place, and its people, despite their religion, still sinned boldly — but their repentance was also bold. Reading the book is to enter into a world in which everyone lives by the Church calendar. Sacred time structures their lives in ways it has not in the West for many centuries. It is a lovely thing.

Once Covid goes away, I’m going to do my best to go back to Norway, and follow a Kristin Lavransdatter pilgrimage path — which, given the kind of book this is, would be both literary and religious, but also would involve a lot of walking in the beautiful Norwegian countryside. The first thing I would have to do is go to Oslo and find my old friend Trude, with whom I lost touch a while back, and thank her for her gift so many Christmases ago, of a novel that has become one of my all-time favorites. Here is what she wrote inside the first of the trilogy she gave me when we were fresh out of college, and working in the same city:

Reading Kristin Lavransdatter, I kept picturing the title character as my blonde friend Trude. The last time we spoke was in Miami Beach, in 1996, I think, as she and her husband were on their honeymoon. I imagine now she and Esper have raised fine children to adulthood, just like Kristin and her husband. Today, on Thanksgiving, I am going to try to find Trude so I can give her thanks for giving me this gift so many years ago — a gift that took almost three decades to manifest its true worth to this bedazzled reader.

My only regret is that I finished Kristin Lavransdatter before it got cold here in Louisiana. This is the perfect big book to read by the fire, with the windows frosted, a cup of hot tea near to hand. Again, make sure you buy the Tiina Nunnally version; it’s important.

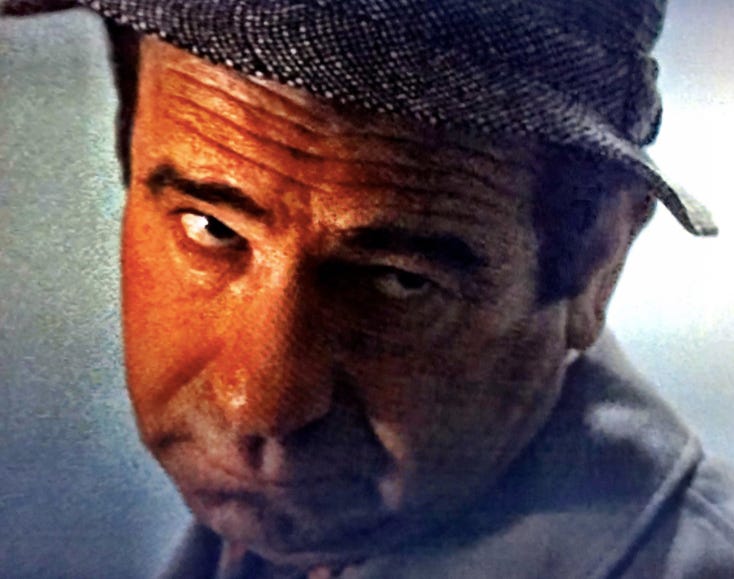

I apologize for sending this epistle so late. I agreed last night to watch The Taking Of Pelham One Two Three with my son Matt, who is home for the holiday. He doesn’t make it home often, so I wanted to spend time with him. I acquiesced to his desire to watch the 1973 New York heist drama, mostly because I wanted to be with him. But man oh man, what a movie! The dialogue is just about perfect — super-gritty, and very New York. Walter Matthau plays a transit cop who has to figure out how to save the lives of hostages that a gang has taken in a subway car, for ransom. Here is a photo of the final image in the movie, which I took from the TV screen with my phone:

All four of us watching the movie spontaneously cheered when we saw that! Walter Matthau for the win! It’s worth watching the entire thing just to get to that scene, and to know why he makes that face. That there is the face of New York City. I went to sleep last night grateful that we had the opportunity to live there for nearly five unforgettable years.

Readers have been sending me photos of themselves and my new book, Live Not By Lies. Behold:

I am grateful to these readers for buying my book, and grateful to all of you for reading this newsletter. Again, I apologize for getting yesterday’s out late, but hey, you get what you pay for, right? I expect to publish another one late tonight, a Thanksgiving edition, from the depths of a turkey-based tryptophan coma.