Listening To 'Living In Wonder'

Chapter 9 ('Signs & Wonders') In Audio; Chapter 1 In Print -- Right Here, Right Now!

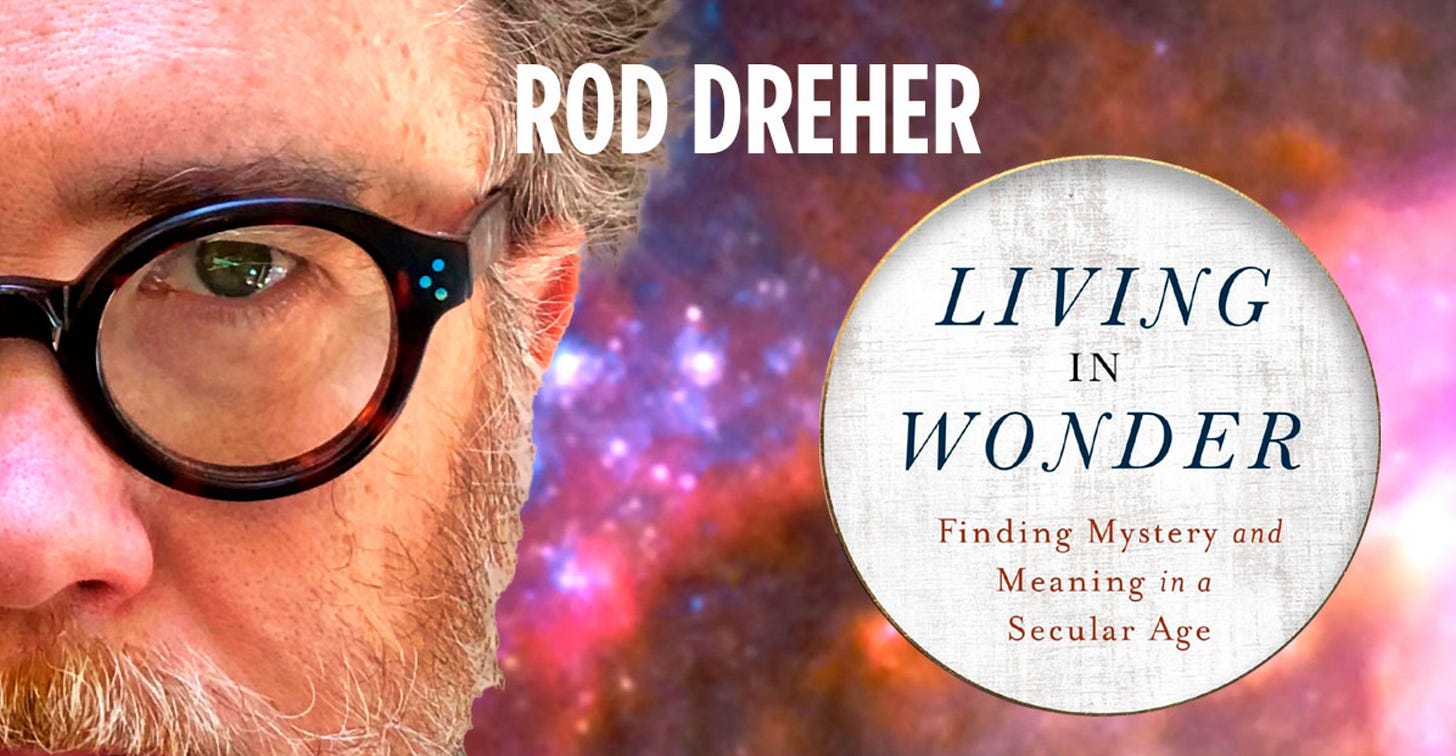

Hey y’all, I just found out that Zondervan has made Chapter 9 of Living In Wonder publicly available from the audiobook. Click here to hear it. It’s the “Signs And Wonders” chapter, full of dazzling stories of life-changing miracles! Even if you don’t plan to buy the book, do give this a listen — it will give you hope, I promise.

By the way, Catholic Tim Stanley of the Daily Telegraph gave a beautiful three-minute talk on BBC Radio 4 today about enchantment, and generously mentioned my book.

Zondervan has also made public Chapter One in PDF form, at this link. Here it is, in full:

Chapter 1

To See into the Life of Things

Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands can think for one who can see. To see clearly is poetry, prophecy and religion, all in one.

—John Ruskin

“The world is not what we think it is.”

You know who told me that? A devout Christian lawyer whose descent into the bizarre reality just beneath the surface of things began when he saw a UFO hovering over a field, which now, years later, has him sorting things out with an exorcist. The man, whom I’ll call Nino, believed in God, in angels, saints, demons, and all the rest before his experience. But then it became intensely real for him in ways he couldn’t have foreseen.

It started in 2009, when teenaged Nino was motoring along a country lane not far from his house in rural New England. He spied a large obsidian-colored craft hovering silently over a field. Nino stared at it for a short time, then drove on. As Nino told me later, “It was as if they planted a seed inside me for later.” Afraid of mockery, he told no one.

Fast-forward to 2016. Nino was a law student in a major American city. One day, studying at his kitchen table, he saw the bare wall of his kitchen begin to swirl. “It was like a portal was opening,” he told me. “The best way to put it is that two humanoid-like beings glitched into reality. They were made of light, but it was like running water. There was a thickness to the air in the room, like if you touched it, it would have made ripples.”

The beings communicated with Nino telepathically. They told him a bird was about to land on his windowsill. Then it happened. Next they said that a car was about to backfire on the street below. That happened too. Then they disappeared.

Nino rushed himself to a nearby hospital and demanded an MRI and blood work. He feared he was losing his mind. But nothing was wrong with him.

The visitors have returned every year since then. After he married, his wife saw them, too, which was a relief, because he knew he wasn’t hallucinating. What’s happening to Nino isn’t unusual. Many who have seen or interacted with UFOs report paranormal experiences in the wake—including visits from beings like the ones that appear to Nino. Some Christians to whom this has happened report that when they speak the name of Jesus in the presence of these beings, the beings vanish.

“Did you ever pray when you saw them?” I asked.

“Oh sure,” Nino said. “Twice. They disappeared immediately.”

“Did that not suggest to you that they might be demonic?”

“You know, I never thought of it that way,” he said. “I kind of figured that they saw they had scared me and wanted to back off. I thought that if they were demons, they would have wanted to fight.”

Nino, a solid, conservative young man with close-cropped hair and an aquiline nose he could have stolen from Dante had been struggling for years to reconcile these experiences with his Catholic faith. We first spoke in early autumn of 2023, not long after he and his wife returned from a trip to Colorado. They had rented a remote cabin. One night, the same thickness Nino experienced during the apparition of the humanoids manifested in the cabin, and all the electronics in the place went crazy.

“I don’t know what this is,” I told him, “but I believe you need to see an exorcist to talk about this.”

The next time I saw Nino, he had been in touch with the official exorcist of his diocese, who suspected the lawyer might be demonically oppressed—not possessed, which is rare, but nevertheless afflicted by harassing demons. Sitting across from me in a hotel in his city, Nino told me he would soon have the church’s required psychiatric evaluation to proceed with the exorcism. He was eager to begin and to make the bizarre visitations cease.

For a man who has been living with something pretty frightening for seven years, Nino struck me as unusually confident, even upbeat.

“If the purpose of these beings is to drive a wedge between me and Christ, they’ve failed,” he said. “Not only did they not drive me away from Jesus, they’ve actually brought me closer to him. This whole thing has made me understand that materialism is false. The world is not what we think it is.”

That phrase is at the core of this book. This is a book about living in a world filled with mystery. It is about learning to open our eyes to the reality of the world of spirit and how it interacts with matter. This is a world that many Christians affirm exists in theory but have trouble accepting in practice. It’s too scary. Even good things that upset our sense of settled order unsettle us. After all, remember the first thing that angelic messengers tend to say to people in the Bible? Do not be afraid! It is natural for us to feel uneasy in the presence of those portions of the world that are normally unseen. And all the more so for us moderns—we prefer to keep God and his movement in the world safely sequestered within a rationalistic, moralistic framework. After all, can’t that be controlled?

But as you will read in the pages ahead, that’s not how the world truly is. It’s more than what we can see. And control? Well, that’s an illusion. Maybe something paranormal has happened to you or to someone you know. Something unsettling or even frightening, but not something you could explain away. And maybe you are like Nino when he first saw the UFO: believing that something real had happened but too afraid of being laughed at to tell anybody.

What happened to Nino terrified him and drove him to Christ to deliver him from evil. But of course this isn’t the only way that our world is expanded by experiences of a larger reality. A man named Ian Norton had a positive encounter with the numinous—the mysterious—that drew him out of a pit of his own making and into the arms of Jesus.

Here’s what happened. It was the day after Easter, in 2022, and I was in the Christian quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City, looking for a special souvenir before I left for the airport later that afternoon. I had just experienced one of the most unforgettable seven days in my life—Holy Week in Jerusalem—and wanted something ancient to remember it by. “I know just the place,” said Dale Brantner, an American pastor and trained biblical archaeologist.

He took me to Zak’s, a narrow antiquities shop in one of the Old City’s ancient streets. Dale said he has known Zak, a Palestinian Christian, for years. Good man. Loves Jesus. Honest. Sells genuine articles. We walked into the shop, but Zak wasn’t there. At the far end of the room, behind a computer, sat a tough-looking white guy, middle aged, with a bald head, fading primitive tattoos on his forearms, and the kind of face that says No funny business, pal.

“Zak’s on his way,” said the man, in a rough Cockney accent belied by the gentleness of his voice. You don’t expect to run into a working-class Londoner in the heart of Jerusalem. He was busy working on the store’s accounts when we Americans walked in. While we waited for Zak, I asked the man—Ian Norton was his name—to tell me how on earth he found himself so far from home.

“I’ve been here thirty-two years,” Ian said. “I was a junkie. I left London for Amsterdam, looking for stronger drugs. Then I heard the heroin was even better in Tel Aviv, so I went there. It was true. But one day I realized that if I didn’t get off it, I was going to die. I went to rehab once, but it didn’t work. I knew I had one last chance.”

The addict found his way to Jerusalem, on a mission to save his own life. Somehow he acquired an English-language New Testament—a book he had never read—then headed out for the banks of the River Jordan. The Cockney desperado vowed that come what may, he was not going to leave the river until he was delivered from the demon of drug addiction. This was a risky strategy. Acute heroin withdrawal can cause muscle aches, fever, chills, nausea, diarrhea, and other dire symptoms. If vomiting and diarrhea are sufficiently severe, patients can die of dehydration.

“I was anticipating the pains to start, and the pains were starting, from not having any heroin, no food, no money, no anything. I was like, This is it, I’ve got to break through this addiction,” he recalled. “So I was sitting by the Jordan River, waiting for the pains to begin, and they were starting to increase. I was reading the book of Matthew for the first time in my life. I got to that point where Jesus was coming to John the Baptist.”

That event, recorded in Matthew 3:13–17, took place at the same river where the suffering Ian sat shivering from withdrawal pains:

Then Jesus came from Galilee to the Jordan to be baptized by John. But John tried to deter him, saying, “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?”

Jesus replied, “Let it be so now; it is proper for us to do this to fulfill all righteousness.” Then John consented.

As soon as Jesus was baptized, he went up out of the water. At that moment heaven was opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and alighting on him. And a voice from heaven said, “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased.”

Ian went on.

“Reading that part, this cloud just appeared. It was all around, coming closer and closer. It crossed the water first, and as it came nearer to me, it was becoming more and more condensed, more concentrated. At first you could just see it. Then it was something you could taste, and you could touch—and I realized that it had wrapped itself around me. It encompassed me, and pressed in. It held me. All I can say about it is that it was total purity, and peace. These wonderful things I had never felt before were just pressing in all around me and holding me in this state of pure love.

“After four days of being held there like that, without anything, it dissipated—and I was free from the struggle with heroin, just like that.”

He staggered back to Jerusalem, weak from having not eaten. He sat on the street, begging, with a sign reading “Hungry and homeless,” which was true. Christian believers came to Ian to share their testimonies. Eventually a pastor from a Messianic Jewish congregation invited the young beggar to live in the church and sort his life out. It was there, more than two decades ago, that he came to believe in Christ, accepted baptism, and started his new life.

Stunned by what I’d heard, I told him that I had just completed a life-changing week of miracle and wonder in Jerusalem, and that it had come to me as a gift of light and balm, just as my life had taken a dramatic, painful turn after my wife filed for divorce. Ian nodded. He got it. That’s what Jerusalem, one of the thin places of the world, where the veil between the seen and the unseen is porous, does to you.

“The first thing you feel when you get here is separation,” he says. “The things that separate us from our Creator, in Jesus, are the attachments we hold to the world. I was born in London, and coming out of London, everything is so worldly. Even if you’re born again, and you’ve given your life to Yeshua Jesus, there’s still that struggle with the things of the world pulling you back to it.

“You come to Jerusalem, and everything is God focused. You’re wrapped in that spirit here. Everything is focused on continuing that journey toward him. Once you’re separated from the things you hold dear, you’re open to the Spirit calling on your heart.”

It’s true. I had just lived it. After only a week in the Holy City, a week of miracles, signs, and wonders, I was headed back to a life in the West that was uncertain, even scary, but also full of hope and renewal.

Things like that happenstance conversation with a shopkeeper make me wonder. How many times over the years, in all the places I have lived around the world, have I walked past people like Ian? Have I missed knowing their stories or, frankly, even caring to know—even though they had been touched in a jaw-dropping way by an encounter with the divine? How might my life have been different had I been open to noticing, with open eyes, open ears, an open mind, and an open heart?

I bet it’s like this for you too. You want to believe that this kind of thing can happen—that the world is, in fact, enchanted, despite what many modern people say—but you find it difficult. Or maybe you believe it already, but God’s presence seems far away. Maybe your faith has become dry, a thing held more in your head than in your heart—or felt in your bones. Whether you are a curious unbeliever, a half-hearted believer, or a believer who wants to explore deeper this world of wonders but don’t know how, this book is for you.

One autumn night in the Hungarian city of Debrecen, a young evangelical man approached me and asked for a word. He was an American exchange student at the local college and had read some of my previous books. “I’m a conservative evangelical and have been all my life,” he told me. “But I’m dying. I mean, I’m like a fish lying on a riverbank, gasping for air. I believe it all, but I am desperate for a sense of enchantment. I’d like you to tell me about Orthodoxy.”

He was talking about Orthodox Christianity, my own faith tradition, to which I converted in 2006. The young man discerned from my writing that Orthodoxy, largely unchanged from the patristic era, with its ancient rituals, ceremonies, candles, incense, and way of seeing the connection between matter and spirit, offers the enchantment he craved. He was right, I think; we have entered an era in which the Western church desperately needs to taste the medicine preserved in the Eastern church.

We will get into that later. But this is not really a book about Orthodoxy. It’s rather a book about the profoundly human need to believe that we live and move and have our being in the presence of God—not just the idea of God, but the God who is as near to us as the air we breathe, the light we see, and the solid ground on which we walk.

As I mentioned, this way of seeing and living the faith is more common today among the Orthodox, who for various historical reasons escaped the passage to modernity, but this experience was standard for Christians in ages past. C. S. Lewis wrote of the mental model of medieval Christians.[i] In the medieval model, everything in the visible and invisible world was connected through God. All things had ultimate meaning because they participated in the life of the Creator. The specifics of that participatory relationship were matters of dispute among theologians, but few if any doubted that this was how the cosmos worked.

This is what sociologists and religion scholars mean when they say the world of the past was enchanted. Yes, the Middle Ages were a time of kings and knights, of castles and tournaments, of sorcerers and superstition and all of that. It was also a time of war, famine, cruelty, and suffering of the sort that we don’t see in Disney versions of the past. But to call that age “enchanted” in the academic sense—and in the sense I mean in this book—is to refer to the widespread belief that, in the words of an Orthodox prayer, God is everywhere present and fills all things. To say this world is enchanted is to say that we live in a world of beautiful and terrible wonders—things that fill us with awe and call us out of ourselves in recognition of a higher and greater reality.

The religion scholar Charles Taylor described the experience of enchantment like this:

We all see our lives, and/or the space wherein we live our lives, as having a certain moral/spiritual shape. Somewhere, in some activity, or condition, lies a fullness, a richness; that is, in that place (activity or condition), life is fuller, richer, deeper, more worthwhile, more admirable, more what it should be. This is perhaps a place of power: we often experience this as deeply moving, as inspiring. Perhaps this sense of fullness is something we just catch glimpses of from afar off; we have the powerful intuition of what fullness would be, were we to be in that condition, e.g., of peace or wholeness; or able to act on that level, of integrity or generosity or abandonment or self-forgetfulness. But sometimes there will be moments of experienced fullness, of joy and fulfillment, where we feel ourselves there.

We typically experience this fullness, says Taylor, in “an experience which unsettles and breaks through our ordinary sense of being in the world, with its familiar objects, activities and points of reference.” This is what we call awe, or wonder. It is a primal experience on which all true religion depends. “We feel ourselves there.”

Nobody can live forever awestruck. In its rituals and trappings, religion is largely an attempt to capture that primal experience of wonder, to make it present again in some way so that its power can penetrate our everyday lives. We want this encounter with a power greater than ourselves to draw us out, to change us, to make us better—to make us, dare we say, holier.

Life ebbs and flows. We feel closer to God in some seasons than in others. Yet in an enchanted society, it is easier to believe in God, to always feel his presence nearby. We are more capable of perceiving meaning in the world, of sensing moral structure that gives our own lives purpose.

Taylor’s take on the medieval model is close to Lewis’s. In the premodern past, people (not only Christians) took for granted that the natural world testified to the existence of God, or the gods. They believed that society was grounded in this divine reality. They believed that spirit was real—not only the souls of men and women, but also angels, demons, and perhaps other discarnate beings. Everything was bound together in a coherent model—a symbol—that gave meaning to our joys and our sorrows in this life.

The social world that sustained this everyday view of enchantment has disappeared. This is not to say that no one still believes in God. It is to say, however, that even for many Christians in this present time the vivid sense of spiritual reality that our enchanted ancestors had has been drained of its life force. Instead, many of us experience Christianity as a set of moral rules, as the bonds that hold a community together, as a strategy for therapeutic self-help, or perhaps as the ground of political commitment. And, yes, it is all of those things. But without the living experience of enchantment present and accessible, and at the pulsating center of life in Christ, the faith loses its wonder. And when it loses its wonder, it loses its power to console us, change us, and call us to acts of heroism. Slowly, imperceptibly, the vibrant life of the spirit ebbs away, and with it ebbs our confidence in ultimate meaning. Maybe even our hope for the future.

That American student in Debrecen knows his Bible. He has all the arguments for the faith clear in his head. But he craves an experience of the “deep magic” of the Christian faith. He longs for a faith like that of the apostle Paul and his team, who traveled through the Mediterranean casting out demons, healing the sick, and defeating unclean spirits and pagan deities by the power of the true God. We read these stories in the book of Acts and marvel at the signs and wonders that were common in the early church.

On summer vacations, Americans sometimes venture to Europe, visit the great medieval cathedrals, and wonder about the kind of faith that could raise such temples to God’s glory from societies that were poorer than our own. We read old tales of miracles, visions, pilgrimages, and religious feasts and feel the poverty of our own religious experience. We dutifully drag ourselves to church on Sunday, we read our Bibles, we follow the law, we work to serve our nation or our community, we stay current with our reading, but we still may wonder, Is this all there is?

No, it’s not. There’s so much more. Ian in the Holy Land knows that. So does Nino in America. So do others you will meet in these pages, who came to Christ through experiences of awe—mostly by meeting Christ or his messengers, or in some cases through encounters with demons or other experiences that sent them running to Jesus for refuge.

The stories are credible, weird, and powerful. The truth, however, is that most of us won’t experience something like what happened to Ian, the strung-out drug addict, or to Nino, the UFO-haunted lawyer. We might not ever meet somebody who has had their world rocked by the supernatural. In fact, most of us will probably carry on through life without witnessing a miracle or some other manifestation of the numinous, and, in any case, we can’t make them happen. And that’s okay. We don’t have to have a close encounter with angels and miracles to experience enchantment. That’s not how God works.

If the cosmos is constructed the way the ancient church taught, then heaven and earth interpenetrate each other, participate in each other’s life. The sacred is not inserted from outside, like an injection from the wells of paradise; it is already here, waiting to be revealed. For example, when a priest blesses water, turning it into holy water, he is not adding something to it to change it; he is rather making the water more fully what it already is: a carrier of God’s grace. If we do have an experience of awe, a moment when the fullness of life is suddenly revealed to us in an extraordinary way, it is more likely to be far more ordinary than a mystical cleansing cloud blowing in from the River Jordan.

We might be like the Austrian Jewish psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl, who, as a ragged inmate digging a trench in a German concentration camp, tried to drive away the despair engulfing him by thinking of his faraway wife. Frankl writes that he suddenly “sensed my spirit piercing through the enveloping gloom. I felt it transcend that hopeless, meaningless world, and from somewhere I heard a victorious ‘Yes’ in answer to my question of the existence of an ultimate purpose. At that moment a light was lit in a distant farmhouse, which stood on the horizon as if painted there, in the midst of the miserable grey of a dawning morning in Bavaria. ‘Et lux in tenebris lucet’—and the light shineth in the darkness.”

Dr. Frankl found the strength to go on that day—and later in his life, to help untold millions through his books about finding meaning in suffering.

Or we might have an experience like the Soviet spy Whittaker Chambers did in the late 1930s, which ultimately led him out of the Communist underground. He was at home watching his adored baby daughter eating in her high chair. “My eye came to rest on the delicate convolutions of her ear—those intricate, perfect ears,” Chambers wrote. “The thought passed through my mind: ‘No, those ears were not created by any chance coming together of atoms in nature (the Communist view). They could have been created only by immense design.’ The thought was involuntary and unwanted. I crowded it out of my mind. But I never wholly forgot it or the occasion. I had to crowd it out of my mind. If I had completed it, I should have had to say: Design presupposes God. I did not then know that, at that moment, the finger of God was first laid upon my forehead.”[iv]

In my own far more homely case, I owe my faith to walking into an old French church on a summer’s day in 1984. I was a bored seventeen-year-old American, the only young person on a coach full of elderly tourists, and I could barely stand the tedium of the long bus ride to Paris. I followed the old folks into the church, because the prospect of sitting on the bus was even more dull.

The church was the Chartres Cathedral, the medieval masterpiece that is one of the most glorious churches in all of Christendom. But I didn’t know that at the time. I stood there in the center of the labyrinth on the nave gazing up at the soaring vaults, the kaleidoscopic stained glass, and the iconic rose window and felt all my teenaged agnosticism evaporate. I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that God was real, and that he wanted me. I remember nothing else about the entire vacation, which was my first trip to Europe, but I can never forget Chartres, because it was where my pilgrimage to a mature faith in God began.

In these three cases, three very different men met the transcendent at the borderline of the material world. A spark crossed the barrier, signaling to the watchers that there was something beyond what could be seen, touched, and heard. It changed their lives.

Enchantment is not about having bespoke mystical experiences. It’s not learning how to ensparkle the mundane world with mental fairy dust to make it more interesting. It’s more than a way to escape the sense of alienation and displacement that many people today feel. Those are all superficial approaches, ones more likely to lead us into deception at best, and at worst—as has happened to curious seekers who have given themselves over to the occult or other distractions and deceptions—spiritual captivity.

No, true enchantment is simply living within the confident belief that there is deep meaning to life, meaning that exists in the world independent of ourselves. It is living with faith to know that meaning and commune with it. It is not abstract meaning, but meaning that lives in and through God, and in his Son, the Logos made flesh. We can know in our bones that life is good, purposeful, and worth living—but also that spiritual evil and forces of chaos exist as well, and we must prepare to battle them, for daily life requires spiritual warfare. For Christians, this is about learning how to live as if what we profess to believe is true. It is also about learning how to perceive the presence of the divine in daily life and to create habits that open our eyes and our hearts to him, as our fathers and mothers in the faith once did.

That was then, but despite the spiritual desert made by modernity, it is also now. You will notice that the manifestations of the awesome of which I’ve spoken so far happened not in the distant fairy-tale past but in the twentieth century, in an era of disenchantment, when things like this are not supposed to happen. But they still do. The world has never been truly disenchanted. We modern people have simply lost the ability to perceive the world with the eyes of wonder. We can no longer see what is really real. The hunger for enchantment has not gone away, because the hunger for meaning, connection, and the experience of awe is part of human nature. But in the absence of trust in tradition, and inside an antinomian culture that effectively denies any transcendence or structures of truth outside of the choosing self, we no longer know where to look, or how.

The point cannot be overstated: the world is not what we think it is. It is so much weirder. It is so much darker. It is so, so much brighter and more beautiful. We do not create meaning; meaning is already there, waiting to be discovered. Christians of the first millennium knew this. We have lost that knowledge, abandoned faith in this claim, and forgotten how to search. This is a mass forgetting compelled by the forces that forged the modern world and taught us that enchantment was for primitives. Exiled from the truths that the old ones knew, we fill our days with distractions to help us avoid the hard questions that we fear can’t be answered. Or we give ourselves over to false enchantments—the distractions and deceptions of money, power, the occult, sex, drugs, and all the allure of the material world—in a vain attempt to connect with something beyond ourselves to give meaning and purpose to life.

Very well: this book will show you how to seek, and how to find. It will help you regain the ability to read signs that reveal the map of the Way to us, and to walk that well-worn path. It is a book about recovering the deeper and richer dimensions of our lives that have been obscured in modern times, because we have forgotten how to see the world as it really is. This will be a work of remembrance, recovery, and healing. To borrow a metaphor from Dante, the supreme Christian poet, this is how we escape the dark wood of late modernity, with its death, depression, and nihilism, and find our way back to the straight path: the same pilgrim trail to God that many centuries of Christians before us walked.

This is not a story about sorting ourselves out in a legal proceeding and rightly ordering our lives according to a plan, to live by the law. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to bring order to a messy life to align it with purpose. For some, it might be the first step toward re-enchantment, but it’s not the same thing as re-enchantment. No, what we are looking for is more akin to breaking down a dam that prevents living water from flowing to a parched and withered garden and restoring it to a flourishing life.

The psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, one of the heroes of this book, claims that the very skills and habits that led modern Western man to such material success have radically impoverished him spiritually and emotionally. They have washed away our sense of living in a world of wonder, meaning, and harmony, and made us miserable.

“Indeed, if you had set out to destroy the happiness and stability of a people, it would have been hard to improve on our current formula,” he writes—a formula that includes rejecting all transcendent values and even the possibility that they might exist. Yet we moderns still insist that our scientific, materialist way of knowing, a way that has brought us far more control over our lives, is the only valid way—a grave mistake that prevents us from doing what we must to restore ourselves to health. McGilchrist puts it like this: “We are like someone who, having found a magnifying glass a revelation in dealing with pond life, insists on using it to gaze at the stars—and then solemnly declares that if only people in the past had had such a wonderful magnifying glass to look through, they’d have known that, on closer inspection, stars don’t actually exist at all.”

Some Christians are suspicious of the word “enchantment” because of its magical overtones. If this is you, put your mind at ease. The literary theorists Joshua Landy and Michael Saler, editors of an academic essay collection exploring re-enchantment from a completely secular angle, say any meaningful form of re-enchantment will recognize that the world holds these realities:

■ Mystery and wonder

■ Order

■ Purpose

■ Meaning, as a “hierarchy of significance attaching to objects and events encountered”

■ The possibility of redemption, for both individuals and moments in time

■ A means of connecting to the infinite

■ The existence of sacred spaces

■ Miracles, defined as “exceptional events which go against (and perhaps even alter) the accepted order of things”

■ Epiphanies, which are “moments of being in which, for a brief instant, the center appears to hold, and the promise is held out of a quasi-mystical union with something larger than oneself”

This, within a thoroughly Christian context, is our goal. If you are not a religious believer, you may think this is impossible. The good news is that you are wrong—and I’m going to tell you why in the pages that follow. And if you are a religious believer who reads this list and sees its goals as far from the dry or shallow kind of Christianity with which you’re familiar, well, read on: you will discover that deep within the traditions of the Christian faith are resources that can illuminate your religious imagination and renew your soul.

My hope is that when you have finished this book, you will undertake a search, or that you will take up again a search that you had put aside. Though I first found Christ as a Roman Catholic, my own quest led me to Orthodox Christianity in 2006, where I came even more strongly to believe that we are all on a path either toward or away from the God who revealed himself in the Bible. Faithful, practicing Christians of all traditions can learn from this book how to deepen their own awareness of God, who fills all things. Lapsed or uncertain Christians can find in this book reasons to give the faith a second look, because it’s weirder and more wonderful than they think. The Christian churches of the East—the Orthodox, and the so-called Oriental Orthodox—have maintained a distinctly more mystical character than their Western brethren. Now, at the end of the Christian age in the West, an infusion of authentic, time-tested mysticism is a gift from the Eastern churches to the suffering West. The young evangelical in Debrecen senses this, which is why he sought me out.

As with my last two books, adherents to non-Christian faiths may not be able to accept all the Christian claims here, but I believe they will nevertheless find much of value that resonates with their own traditions’ teachings. Unbelievers will struggle with parts of this book, but I hope they will at least come away from it with minds more open to the possibility that God exists and that there really is a transcendent realm. All readers of this book should come away with eyes that can see more deeply into the world, beneath the surface, into the truth of things.

A friendly warning: learning how to see for enchantment is not going to be easy. It is going to cost you something. In fact, it has to. In the medieval masterpiece The Divine Comedy, the greatest story of Christian re-enchantment ever told, the pilgrim Dante can’t escape the prison of the dark wood without putting himself in the hands of a trustworthy guide. That guide, the poet Virgil, takes him on a long and arduous pilgrimage of repentance and rebuilding the inner life so that Dante can bear the weight of God’s glory. Repentance begins with the sacrifice of control—and that can be frightening.

The thing is, enchantment that doesn’t compel you to change your life is not enchantment at all. It’s going to be hard to make this journey back to a richer and more vital understanding of our spiritual lives, but what else can we do? As Virgil says to Dante when they first met in the forest clearing, if you stay here, you’re going to die. I am convinced that the only way to revive the Christian faith, which is fading fast from the modern world, is not through moral exhortation, legalistic browbeating, or more effective apologetics but through mystery and the encounter with wonder. It’s not going to come quickly or without struggle. A pilgrimage is not the same as a three-hour tour.

The philosopher Elaine Scarry says that education is the process of training people to be looking at the right corner of the sky when the comet passes. This book is what I worked on while I waited, hoping that through the things I would discover along the way I would learn how to see what is right in front of me—which is to say, to perceive in the everyday and the commonplace the comet blazing across the night sky.

The world is not what we think it is. It is far more mysterious, exciting, and adventurous. We have only to learn how to open our eyes and see what is already there.

There is is, Chapter One. If you want to read the rest, well, pre-order it here! I do hope that some of you will make it to the book launch in Birmingham next week (Oct 21): click here for more info and to register.

You also will have heard that Paul Kingsnorth is speaking on Friday night October 18 in Birmingham — you need to buy a ticket here.

On Saturday morning, why not come pray with Paul and me at the Holy Trinity + Holy Cross Greek Orthodox church in Birmingham, then have breakfast with us and talk with us about the Orthodox faith? Register for that here (and you do need to register, so the church can make sure it has enough to eat for everybody.

I’m at the gate in Philly connecting through to Birmingham. Looking forward to events of the next few days!

This post is free for everybody — forward it on to those who need to read it (or hear it).

I am purposely not reading this or listening because I want to read the whole book together in it’s entirety. Lol.

I like your point about ‘thin places’. I definitely think those exist. Is it an Irish expression originally?