Lunch With The Unknown Soldier

And: Trans Tyranny In Starmerstan; AI Drones; Goodbye Reality; Dark Age Saints

This image of a beggar cooking a meal over the Eternal Flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Brussels made the rounds on X yesterday. It was claimed that this is an “illegal migrant,” but there is no reason to believe that. In fact, the original image is from four years ago, where the man is identified only as “homeless.” In fact, if you follow that link to the original post, the hands of the beggar are not brown or black, but white. So it is doubtful that he is an illegal migrant, or a migrant at all.

Nevertheless, this is an incredibly powerful condensed symbol of what Belgium, and much of Europe, has become: indifferent or even hostile to its own sacred traditions. The original poster of this and related images is Theo Francken, a prominent Belgian politician and minister, who remarked at the time:

Brussels is in fast decline due to 20 years of socialist policy. Criminality, drugs, poverty, illegal migration, police demotivation… are a horrible mix. We want our capital back!

Good luck with that, Mr. Francken. In Germany, it looks like the establishment will go to extraordinary lengths to prevent changing the status quo. You’re going to find this hard to believe, but it’s true: in Cologne, all the parties contending for local elections on September 14 — except for the anti-migrant Alternative for Germany (AfD) — have vowed not to speak ill of migration during the campaign. They somehow believe that by ignoring the No. 1 issue on German voters’ minds, they can make it go away. They’re simply ceding the issue to the AfD.

You’re going to find this even harder to believe: over the last couple of weeks, as election day draws near, six AfD candidates for office in North Rhine-Westphalia — where Cologne is — have died. Six! What are the odds? As I write in The European Conservative today:

To be sure, AfD isn’t a threat to win in these upcoming local elections. In North Rhine-Westphalia, the Christian Democrats are comfortably ahead of the pack, polling at 36%, followed by the Social Democrats at 23%. AfD is in third place, with just shy of 16%.

Still, the party has trebled its support there since the last election, and the establishment parties are running scared. Last week, all the political parties (except AfD) in Cologne, a North Rhine-Westphalia city of 1.1 million, vowed not to criticize migrants or migration during the campaign.

Under the so-called fairness pact, parties said they will “not campaign at the expense of people with a migrant background living among us” and will not blame migrants “for negative social developments such as unemployment or threats to internal security.”

This development is especially bizarre given that Cologne was the site of mass sexual assaults of German women by Arab and African men on New Year’s Eve 2015-16. According to German police, of the 153 suspects identified in the attacks, two-thirds were from either Morocco or Algeria, 44% were asylum seekers, and another 12% were probably in Germany illegally.

Yet political elites in the very city where these atrocities took place have gagged themselves for the greater good of Germany. This leaves AfD as the only party willing to talk about migration as a problem—if their candidates survive the next two weeks.

Someone on X said this is not mysterious at all, listing the politicians and their causes of death:

René Herford (pre-existing liver disease; kidney failure), Patrick Tietze (suicide), Ralph Lange (pre-existing illness), Wolfgang Klinger (pre-existing illness), Wolfgang Seitz (pre-existing illness, heart attack), Stefan Berendes (natural death)

I hope he’s right, and this is just a coincidence. The alternative is too horrible to contemplate. Yet given the lengths to which the German state is going to suppress AfD, nothing would surprise me.

Trans Tyranny In Starmerstan

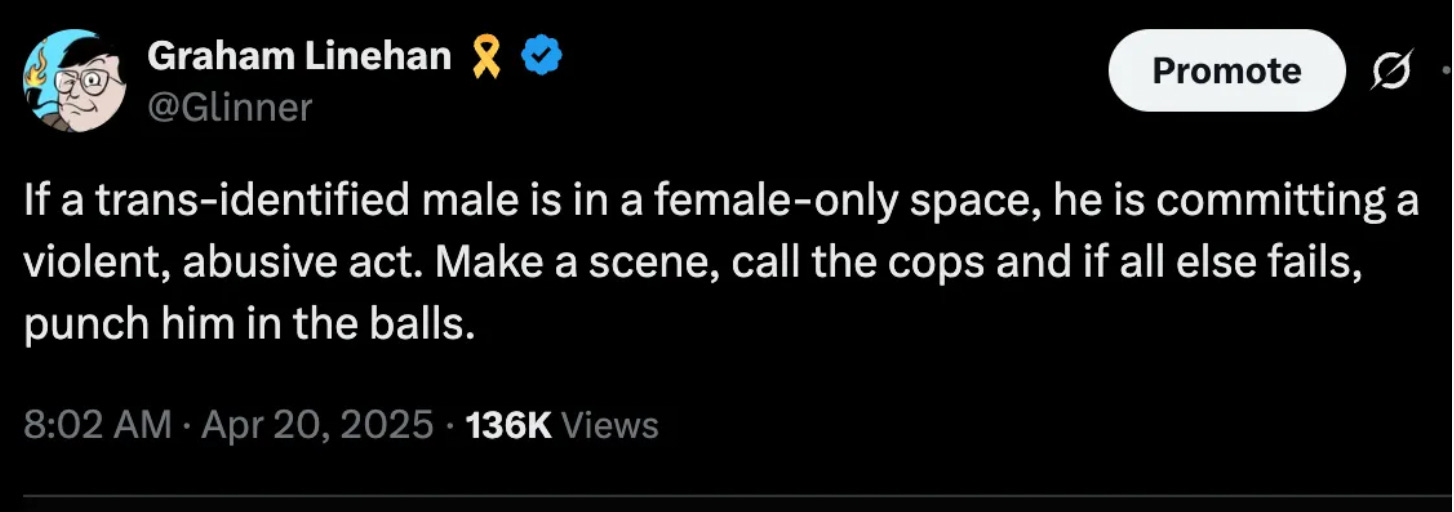

Each day brings news of Britain’s descent into madness. The comic actor Graham Linehan, who is despised by the trans community for his horrible, awful, no-good belief that penis-havers cannot be women, was just arrested under jaw-dropping conditions. He writes:

Something odd happened before I even boarded the flight in Arizona. When I handed over my passport at the gate, the official told me I didn't have a seat and had to be re-ticketed. At the time, I thought it was just the sort of innocent snafu that makes air travel such a joy. But in hindsight, it was clear I'd been flagged. Someone, somewhere, probably wearing unconvincing make-up and his sister/wife’s/mum’s underwear, had made a phone call.

The moment I stepped off the plane at Heathrow, five armed police officers were waiting. Not one, not two—five. They escorted me to a private area and told me I was under arrest for three tweets. In a country where paedophiles escape sentencing, where knife crime is out of control, where women are assaulted and harassed every time they gather to speak, the state had mobilised five armed officers to arrest a comedy writer for this tweet (and no, I promise you, I am not making this up.

You have to read his entire account to believe it. He had to be hospitalized because while in custody, his blood pressure spiked into stroke territory. Linehan concludes:

I was arrested at an airport like a terrorist, locked in a cell like a criminal, taken to hospital because the stress nearly killed me, and banned from speaking online—all because I made jokes that upset some psychotic crossdressers. To me, this proves one thing beyond doubt: the UK has become a country that is hostile to freedom of speech, hostile to women, and far too accommodating to the demands of violent, entitled, abusive men who have turned the police into their personal goon squad.

This is today’s Britain. If you are a tranny or a tranny-ally, you can go into the streets calling on people to “punch a TERF” (Trans-Exclusive Radical Feminist), and nothing will happen to you. At some point, the place is going to blow. Normal people cannot bear this indefinitely.

Note well that this outrageous attack on free speech will likely not be reported in the US media. So much real and important information that goes against the Narrative can only be learned on X and Substack. Thank you for subscribing. I know this newsletter is hard to read some days, but I try to keep you informed about things that matter.

Attack Of The AI Drones

The Wall Street Journal reports today (paywalled) that Ukraine has launched swarms of killer drones against Russia. Excerpts:

The assault was an example of how Ukraine is using artificial intelligence to allow groups of drones to coordinate with each other to attack Russian positions, an innovative technology that heralds the future of battle.

Military experts say the so-called swarm technology represents the next frontier for drone warfare because of its potential to allow tens or even thousands of drones—or swarms—to be deployed at once to overwhelm the defenses of a target, be that a city or an individual military asset.

Ukraine has conducted swarm attacks on the battlefield for much of the past year, according to a senior Ukrainian officer and the company that makes the software. The previously unreported attacks are the first known routine use of swarm technology in combat, analysts say, underscoring Ukraine’s position at the vanguard of drone warfare.

Swarming marries two rising forces in modern warfare: AI and drones. Companies and militaries around the world are racing to develop software that uses AI to link and manage groups of unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, leaving them to communicate and coordinate with each other after launch.

Here’s the kicker: AI is deciding the attack.

But the use of AI on the battlefield is also raising ethical concerns that machines could be left to decide the fate of combatants and civilians.

The drones deployed in the recent Ukrainian attack used technology developed by local company Swarmer. Its software allows groups of drones to decide which one strikes first and adapt if, for instance, one runs out of battery, said Chief Executive Serhii Kupriienko.

“You set the target and the drones do the rest,” Kupriienko said. “They work together, they adapt.”

More:

But the rise of AI in war is raising ethical concerns about the potential for machines to make life-or-death decisions without human oversight. The United Nations has, for example, called for regulation of lethal autonomous weapons.

The U.S. and its allies require a person in the so-called kill chain under current rules of engagement.

Swarmer said a human ultimately makes the decision on whether to pull the trigger.

“Folks have been talking about the potential of drone swarms to change warfare for decades,” said Kallenborn. “But until now, they’ve been more prophecy than reality.”

The future is now. It is difficult to imagine a country not giving power to these AI-powered drones to initiate strikes themselves if human controllers are incapacitated. I dunno, this feels mighty apocalyptic to me.

Goodbye, Reality

Gosh, today’s newsletter is dark. But attention must be paid. Ted Gioia writes about how AI is on the verge of erasing any shared reality. Excerpts:

In the last few months, reality has been defeated—totally, completely, unquestionably.

It is now possible to alter every kind of historical record—perhaps irrevocably. The technology for creating fake audio, video, and text has improved enormously in only the last few months. We will soon reach—or may have already reached—a tipping point at which it’s impossible to tell the difference between truth and deception.

For example:

Can I tell the difference between a fake AI video and a real video? A few months ago, I would have said yes. Now I’m not so sure.

Can I tell the difference between fake AI music and human music? I still think I can discern a difference in complex genres, but this is a lot more difficult than it was only a few months ago.

Can I tell the difference between a fake AI book and a real book by a human author? I’m fairly confident I can do this for a book on a subject I know well, but if I’m operating outside my core expertise, I might fail.

At the current rate of technological advancement, all reliable ways of validating truth will soon be gone. My best guess is that we have another 12 months to enjoy some degree of confidence in our shared sense of reality.

But what happens when it’s gone?

Gioia says that we will see far more mental breakdowns among the unstable. But that’s not the worst thing:

The problems among sane, healthy people may be even worse than among the psychically fragile. These stable individuals are essential to the smooth running of society—but they will no longer have the shared basis of reality we once took for granted. They will have their own beliefs, and their own experiences—but others may now refuse to acknowledge them. That’s because all evidence is tainted. In a world with pervasive deception, everything demands skepticism.

Consider those who believe that the moon landing never happened. Now imagine a world in which everybody is like that about everything—because nothing can be proven.

Seems like every day I have cause to think about Hannah Arendt. You will recall that one of her conditions that gives rise to totalitarianism is a society in which people no longer care about the truth, only what feels right to them. Well, what about a society in which even people who care about the truth can’t know for sure what it is? And how do you know that some source of information you’ve come to trust isn’t really an AI masquerading as a human? What does that do to your capacity to create psychological stability?

What if the same AI that directs drones to swarm military targets decides to “swarm” informational channels with lies? How the hell do we defend against that?

Gioia:

To start, we need mechanisms for preserving the past that can’t be tampered with by technology. Physical books are an example—I have thousands of these, and every one of them is immune to the schemes of bots and technocrats.

But books aren’t enough. We need other sources of information that are as impregnable as books. Institutions and businesses, including universities, newspapers, libraries, and nonprofits, should play a role in cultivating these sources. But many of these institutions are embracing the same technologies that have caused the harm. I fear that few of them grasp the magnitude of the threat, or the role they now need to play.

This is one key aspect of the Benedict Option: as with the Dark Age monasteries, create repositories of real information. Not only will it be vital during the chaos to come, but it will be necessary to rebuild society after the inevitable catastrophe.

In Rome, there is talk that Pope Leo will devote his first encyclical to AI. I hope so. We are on the verge of something very, very big — something of world-historical proportions.

On Sunday, before I left Rome, I had a long lunch with a friend. We were talking about the general anxiety and malaise that we are observing everywhere. I shared with him some of the things people told me at Midwestuary, about the grave mental distress and breakdowns of individuals, and relationships, that they are seeing all over now. It’s only going to get worse. I confess that when I started writing The Benedict Option about a decade ago, I did not foresee the coming of AI, and what it would do to our capacity to form communities. Given the limits of my imagination, I could not have thought that people would be so lonely that they would form what they consider to be meaningful relationships with machines they know to be fake, but which can mimic human behavior so well that lonely people prefer the fake to the real.

But here we are. This situation was prepared by a therapeutic mindset that treats achieving a feeling of well being as the highest good in life. Hundreds of millions of us will prefer the slavery of Egypt to the freedom of the Sinai desert. We will choose the blue pill that keeps us bound to the Matrix, and imagine ourselves happy.

What would Father Kolakovic say to us today, to help us prepare to resist being merged with the Machine, and thereby save our very humanity? I have a feeling that Paul Kingsnorth’s new book, Against The Machine (out September 23), is appearing at exactly the right time. Do buy a hard copy, so some future AI can’t erase it.

Call me crazy, but let me remind you what “Jonah,” the ex-occultist, told me that the demons he used to channel told him: that their plan is to merge humanity with the Machine as a way of enslaving us and destroying us. That sounded far out to me when he told me only two years ago. It doesn’t anymore.

Stop Marginalizing AI, You Bigot!

I’m guessing this is a joke, but with The Guardian, you never know. Excerpt:

Name: Clanker.

Age: 20 years old.

Appearance: Everywhere, but mostly on social media.

It sounds a bit insulting. It is, in fact, a slur.

What kind of slur? A slur against robots.

Because they’re metal? While it’s sometimes used to denigrate actual robots – including delivery bots and self-driving cars – it’s increasingly used to insult AI chatbots and platforms such as ChatGPT.

I’m new to this – why would I want to insult AI? For making up information, peddling outright falsehoods, generating “slop” (lame or obviously fake content) or simply not being human enough.

Does the AI care that you’re insulting it? That’s a complex and hotly debated philosophical question, to which the answer is “no”.

Then why bother? People are taking out their frustrations on a technology that is becoming pervasive, intrusive and may well threaten their future employment.

Clankers, coming over here, taking our jobs! That’s the idea.

Where did this slur originate? First used to refer pejoratively to battle androids in a Star Wars game in 2005, clanker was later popularised in the Clone Wars TV series. From there, it progressed to Reddit, memes and TikTok.

Dark Age Saints, AI Pastors, And John Calvin

As you know, I’ve been burying myself in Church history, to prepare for my new book project. Let me tell you, as messy as you might imagine the spread of the Gospel to have been, it was even messier. Here is a passage from the great Church historian Christopher Dawson, in his Religion And The Rise of Western Culture, about how the faith was first transmitted and accepted by the barbarians of western Europe:

In the Dark Ages the saints were not merely patterns of moral perfection, whose prayers were invoked by the Church. They were supernatural powers who inhabited their sanctuaries and continued to watch over the welfare of their land and their people. Such were St. Julian of Brioude, St. Caesarius of Aries, St. Germanus of Auxerre —such, above all, was St. Martin, whose shrine at Tours was a fountain of grace and miraculous healing, to which the sick resorted from all parts of Gaul; an asylum where all the oppressed—the fugitive slave, the escaped criminal and even those on whom the vengeance of the king had fallen—could find refuge and supernatural protection.

It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of the cult of the saints in the period that followed the fall of the Empire in the West, for its influence was felt equally at both ends of the social scale—among the leaders of culture like Gregory of Tours and St. Gregory the Great and among the common people, especially the peasants who, as “pagani”, had hitherto been unaffected by the new religion of the cities. In many cases the local pagan cult was displaced only by the deliberate substitution of the cult of a local saint, as we see in Gregory of Tours’ description of how the Bishop of Javols put an end to the annual pagan festival of the peasants at Lake Helanus by building a church to St. Hilary of Poitiers on the spot to which they could bring the offerings which had formerly been thrown into the waters of the sacred lake.

In this twilight world it was inevitable that the Christian ascetic and saint should acquire some of the features of the pagan shaman and demigod: that his prestige should depend upon his power as a wonder-worker and that men should seek his decision in the same way as they had formerly resorted to the shrine of a pagan oracle.

Nevertheless it was only in this world of Christian mythology—in the cult of the saints and their relics and their miracles-that the vital transfusion of the Christian faith and ethics with the barbaric tradition of the new peoples of the West could be achieved. It was obviously impossible for peoples without any tradition of philosophy or written literature to assimilate directly the subtle and profound theological metaphysics of a St. Augustine or the great teachers of the Byzantine world. The barbarians could understand and accept the spirit of the new religion only when it was manifested to them visibly in the lives and acts of men who seemed endowed with supernatural qualities. The conversion of Western Europe was achieved not so much by the teaching of a new doctrine as by the manifestation of a new power…

I have this intuition that something similar is going to be needed for the faith to survive and grow among the neo-barbarians of our time. The seed of this intuition led to Living In Wonder. I don’t think that standard Christian apologetics or ways of engaging the world are going to be sufficient for this coming world of AI false enchantment.

You might remember my telling you recently about a friend who made an observation and asked a question onstage at Midwestuary about Protestant pastors eager for AI to help them become more effective ministers by turning them into online avatars. She told the audience and we members of a panel that she was the only one in the room who thought this was problematic. This friend, Courtney Trotter, has sent me some of her writing. This below is part of her PhD application. She was trained at a leading Protestant low-church seminary, and today teaches Hebrew, but living among and trying to minister to educated unbelievers challenged her in ways that caused her to convert to Orthodoxy. She writes:

Modernism is the realm in which the New Atheists reigned, relegating Christianity and all other religions to the dust bin of evolutionary utility. The modern man, whether spiritual or not, was all too comfortable separating the world into two stories – the natural and the supernatural, material and immaterial, which became all too easy to dismiss as real and non-real.

The modern separation between heaven and earth is responsible for the dehumanization of man and the desacralization of nature. Modern disenchantment is reflected in today’s widespread reluctance to acknowledge that God is embodied and that both the exitus (creation) and the reditus (redemption) depend upon this divine embodiment. To become modern means to inhabit a disenchanted, disembodied, and ultimately Gnostic universe.

Though, this is not the realm in which my youth, post-Christian America, or the religious “Nones” exist. They are not modernists. Surprisingly, the death of God did not lead to the death of spirits. A demythologized cosmos did not lead to the end of myth. Disenchantment instead led to re-enchantment via a maze of successor ideologies and DIY spiritualities.

The first time we met, Courtney told me that in the scholarly and tech-oriented community in which she lives, she and her husband encounter people all the time who have no time for Christianity, but who are dabbling in paganism and the occult to fill the spiritual void. More:

These Nones are still skeptical, not in the modernist, fact-value, evidentialist sort of way. But skeptical of how a religion, especially an exclusive religion, accords with reality as an experiential phenomenon. What if Jesus rose from the dead? How does that affect me and what I do? How can that propositional truth be experienced today?

The Four Horsemen of New Atheism fell back behind The Four Horseman of Meaning in the cultural imagination: Bishop Barron, John Vervaeke, Jonathan Pageau, and Jordan Peterson.

Even if these figures are still unknown to the man on the street, they were articulating ideas that were widely held and deeply felt. Specifically in my case, Vervaeke’s 4P/3R model of cognition was a new way to conceive of the benefit of liturgical formation and its relationship to scientific knowledge. Science is a communal, traditioned knowledge that engages in unvarying procedure in order to receive feedback from and participate in a dynamic relationship with an unseen realm.

Except for the fact that this realm is accessible through a microscope and experimental protocol, it is all too similar to the type of formation that one undergoes in a religious community. The twin realities of discovery and theophany were suddenly the bridge between the sanctuary and the laboratory.

While studying the tabernacle and sacrifices, I came across the work of Mircea Eliade, a scholar of religion from the mid-20th century, who also happened to be referenced in these cultural conversations in what would be dubbed “the meaning crisis.” Why was he significant for both?

This summary of the Eliade’s work by Michael Meade showed me the inherent relationship between my ministerial and cultural contexts:

Without conscious rituals of loss and renewal, individuals and societies lose the capacity to experience the sorrows and joy that are essential for feeling fully human. Without them life flattens out, and meaning drains from both living and dying. Soon there is a death of meaning and an increase in meaningless deaths.

There could hardly be a more fitting description of our age, haunted by its spiritual memory and yet anxious of the uncertain future. Many commentators have noticed this profound societal shift and the ways in which it appears to be trickling into society from the top down. What answers does the church have for it? The univocal answer of the early church with regards to meaning was lex orandi, lex credendi with its summit seen as a Eucharistic theophany – Christ in our midst.

The answer was found in liturgy and sacrament, creed and prayer, calendrical enactment of time and eternity, fasting and feasting. Yet, I inherited a liturgical tradition that chided ritual, privileged innovation, and taught against sacramental presence. There were certain movements within modern evangelicalism that were making compelling arguments for retrieval. Nevertheless, the efforts were often piecemeal (a doctrine here, a practice there) and lacked a coherent, grounding theological framework, metaphysic, or an ecclesiastical communion. Through my own long path, all of this led me to Eastern Orthodoxy.

She is now an Orthodox catechumen. Courtney went on to say in a personal comment to me (which she gave me permission to share) that asking the question about disembodiment in the age of AI onstage at Midwestuary had an effect:

I've also been communicating with a flood of people who want to talk to me after asking that question — many of them Protestants. All of them acknowledge that question revealed the depth of the disembodied problem in Protestantism. I think where the disconnect comes in — some people are in sacramentally oriented traditions like Anglicanism or Lutheranism, or they are in churches where it seems like the specter of AI is so far away. It's hard to imagine their pastor having an avatar.

But what they do not realize is that in Big Eva publishing and parachurch [organizations] are the de facto ecclesial hierarchies. Books get promoted across denominations, and authors make the conference circuit, eroding the boundaries of denominationalism.

This consultant [who was trying to convince the pastors to use his AI program to turn themselves into avatars] was not a part of my denomination, but he was brought in to talk about how to "leverage" AI for your ministry. That's how it works.

The specter of AI might be far off in their personal church, but it is already being promoted and packaged for their pastors. More than likely their pastor is already using AI to write their sermons — an Anglican friend from the conference asked me how to convince her pastor that this was a problem. So it is in the sacramental Protestant world too — just not full throttle like it is in low church evangelicalism.

One more:

Your readers who are pushing back just probably aren't seeing the problem proximal to them and don't see it coming. I've had this conversation countless times with friends in ministry who give me the same pushback or bewildered looks...until one day, they call me because they need to navigate the sad consequences of this issue in their church. Better for everyone to get prepared now.

I’m not quite sure how this ties in to what Dawson said about the shamanistic qualities of the Dark Age saints, and how they needed to be seen that way by the barbarians in order for the barbarians to take the Gospel seriously. Maybe it’s this: AI will produce such artificial wonders that priests and pastors are going to have to live and preach as if being an ordained Christian leader is about far more than being a mere conduit of information about God.

In Living In Wonder, I write about an argument I once got into with a low-church Protestant (I think a Pentecostal, but I’m not sure) who believes that going to church in the Metaverse — where everyone meets in virtual space, as an avatar — is the future of Christianity. I could not convince him otherwise. For him, the experience of Christian worship is entirely about information transferral and creating a shared emotional experience of God — and that is something that can be done in virtual space. He’s not wrong, given his metaphysical presuppositions. For him, Christianity is something that happens in the mind.

I’m not questioning the validity of his faith in Christ. I’m questioning how that kind of Christianity will be able to survive the disembodiment of humanity in the age of AI. That, and how it forms what we believe is human.

Courtney sent me this link to a long, rich discussion by Robin Mark Philips about John Calvin and nominalism. I cannot possibly do justice to it by quoting it at length or even summarizing it. But I will offer a couple of passages:

Recall that a theological corollary of Ockhamist metaphysics had been that God and the world compete for the same ontological space. In what we might call a “zero-sum theology,” God’s absolute freedom came to depend on Him not being controlled by the stuff of the natural world; the tendency was, as Oakley put it, “to set God over against the world.” When this implicit dialectic entered into the theological imaginations of the reformers, it found expression in the notion that the problem with objects, places and feast days being “charged” with an extraordinary spiritual potency is that they seem to bind God, to contain His sovereignty within the stuff of materiality. As Charles Taylor observed, summarizing the thinking of the time,

“Treating anything as a charged object, even the sacrament, and even if its purpose is to make me more holy, and not to protect against disease or crop failure, is in principle wrong. God’s power can’t be contained like this, controlled as it were, through its confinement in things, and thus ‘aimed’ by us in one direction or another.”

The concern behind this desacralization was the preservation of God’s ultimate sovereignty and His transcendence from the natural world, yet the operative presupposition was the nominalist antinomy between grace and nature, between Providence and creation.

As the sanctuary came to lack a sense of intrinsic spiritual worth or significance, its value for the life of the worshiping community became entirely instrumentalized rooted in its functional value as a place where people could be protected from the elements. Consistent with this new drive, Calvin urged that places of worship be locked during the week to prevent them being used as places of prayer. As he stipulated, “If anyone be found making any particular devotion inside or nearby, he is to be admonished; if it appears to be a superstition which he will not amend, he is to be chastised.” Commenting on this stipulation, Dyrness remarked that for Calvin, the church

“was the stage on which the performance of worship was played out, and when that was finished, the place had no further role to play…. Worship was everywhere, but it was nowhere in particular. The space of worship was in practice abolished. …This emptiness is the reverse side of the positive impetus to see one’s Christian vocation, and the glory of God, diffused throughout all of life, as Calvin liked to say….

“Objects and actions inevitably did come to fill Protestant spaces. Pews, pulpits, and tables—all these could become beautiful objects, but they had no intrinsic religious significance and the space they occupied had a strictly utilitarian function….”

More:

[Calvin’s] failure to recover an earlier sacramentalism had enormous implications in his understanding of time and place. A desacralizing tendency was let loose in the world as the sacred became ubiquitous. The church became locked, not because the building was no longer considered a sacred location for prayer, but because everywhere was seen to be a location for devotional piety. However, what was ostensibly a quantitative enlargement of the sacred was also a qualitative transformation of it. Indeed, the move from sacred particularity became a move towards disenchantment, as definite times and places could no longer function as avenues for a more specific integration of the physical and the spiritual.

If conflating the distinction between the sacred and the profane meant that everything could become sacred, in another sense it meant that nothing could any longer be considered sacred. This resulted in two instincts that seem mutually exclusive but which both emerged organically from the narrative of Sola Dei Gloria. One instinct was to glorify God by seeing the finite charged with the infinite, while the other was to preserve God’s glory by making sure the infinite and the finite are never mixed. If the former seemed to result in a new valuation of the world and humankind’s experience living within the theatre of God’s glory, the latter involved a principled commitment to the non-integration of the physical with the spiritual.

This is all helpful to my understanding (and of course I very much welcome critique and commentary from Calvinists and Calvin-inspired Protestants).

Courtney suggests that the epilogue to C.S. Lewis’s final work, The Discarded Image, offers a way that modern people — including Protestants who reject sacramentalism — can recover at least some of it. In this passage, Lewis refers to the “Medieval Model,” a sacramental and hierarchical way of imagining the cosmos. Lewis is clear that he does not believe in the Model, though he does think there was a lot of truth in it:

I hope no one will think that I am recommending a return to the Medieval Model. I am only suggesting considerations that may induce us to regard all Models in the right way, respecting each and idolising none. We are all, very properly, familiar with the idea that in every age the human mind is deeply influenced by the accepted Model of the universe.

But there is a two-way traffic; the Model is also influenced by the prevailing temper of mind. We must recognise that what has been called ‘a taste in universes’ is not only pardonable but inevitable. We can no longer dismiss the change of Models as a simple progress from error to truth. No Model is a catalogue of ultimate realities, and none is a mere fantasy. Each is a serious attempt to get in all the phenomena known at a given period, and each succeeds in getting in a great many.

But also, no less surely, each reflects the prevalent psychology of an age almost as much as it reflects the state of that age’s knowledge. Hardly any battery of new facts could have persuaded a Greek that the universe had an attribute so repugnant to him as infinity; hardly any such battery could persuade a modern that it is hierarchical. It is not impossible that our own Model will die a violent death, ruthlessly smashed by an unprovoked assault of new facts—unprovoked as the nova of 1572.

But I think it is more likely to change when, and because, far-reaching changes in the mental temper of our descendants demand that it should. The new Model will not be set up without evidence, but the evidence will turn up when the inner need for it becomes sufficiently great. It will be true evidence. But nature gives most of her evidence in answer to the questions we ask her. Here, as in the courts, the character of the evidence depends on the shape of the examination, and a good cross-examiner can do wonders. He will not indeed elicit falsehoods from an honest witness. But, in relation to the total truth in the witness’s mind, the structure of the examination is like a stencil. It determines how much of that total truth will appear and what pattern it will suggest.

When you read the work of modern thinkers like Iain McGilchrist, John Vervaeke, and Thomas Nagel, all of whom draw on the most up-to-date science to support the idea that in some sense, consciousness interacts with matter, you get an idea of what Lewis meant. I doubt this will make sacramentalists of strict Calvinists, but it might at least open the minds of some non-sacramental Christians to revision. As Courtney Trotter points out, a radical separation of the body from the mind leaves Christians who think in that way especially vulnerable to deception from AI and digital culture.

You write, “Note well that this outrageous attack on free speech will likely not be reported in the US media. So much real and important information that goes against the Narrative can only be learned on X and Substack. Thank you for subscribing. I know this newsletter is hard to read some days, but I try to keep you informed about things that matter.” In fact, this newsletter is remarkably easy to read because your writing is so lucid and your take on an extraordinarily wide range of subjects never fails to engage me. That the subject matter is sometimes hard to bear is simply because the world is sometimes hard to bear. You at least make reading about the hard-to-bear world interesting.

By the way, I will be adding clanker to my vocabulary. I could have used it last week when “Darren,” the hotel-booking AI assistant, attempted to engage me in normal conversation. Because Darren sounded very suspicious, I asked, “Are you a human or are you a robot?” He replied that he was in fact AI but then hurriedly added some anodyne gobbledygook about how he “would like to believe that I am capable of answering all your questions and . . . “ “REPRESENTATIVE!” I shouted. He tried pleading his case again and again I shouted “REPRESENTATIVE!” I sure wish I had known to shout “I said Representative, you clanker!”

Thanks for all your hard work and excellent writing, Rod. Stay safe out there.

There are two questionable assumptions in today’s blog first, that Calvinism has “….thrown all the mystery out;” and second, that Christian mysticism provides a way for God to reveal spiritual knowledge about Himself and His being to humankind.

\

To start it helps to be precise in our definitions. Christian mysticism involves seeking direct spiritual knowledge through direct communion with the Divine. Mystery describes something that is difficult to explain or beyond human comprehension.

It’s easy to understand why non-Protestants believe Protestants reject mysticism and mystery because the stereotypical face of Protestantism that most outsiders see are mainline Protestant denominations and big box evangelical churches. Mainline Protestant denominations, particularly those of a more liberal bent, have made God very small, unmysterious and remote by applying historical criticism to their exegesis of scripture and postmodernism to the application of their Christianity and to their worship services. Big box evangelical churches still have a very big God, but their emotion filled, entertainment and conversion-focused seeker sensitive worship services obscure any element of mystery in their practiced theology. These churches believe in the mystery of the anointing of the Holy Spirit in conversion and the mystery of the indwelling of the Holy Spirit in a Christian’s life, but that mystery is obscured by their weekly focus on the conversion experience, praise bands, smoke machines, large video screens and jeans-clad tattooed pastors.

A group of Protestants that are less visible and who do not feed into this stereotype are traditional, creedal orthodox Calvinist or Reformed Protestants. These Protestants believe that mysticism as a means to find and experience the Divine is unscriptural and dangerous, however, they do believe that mystery in Christianity is alive and well. John Calvin rejected Christian mysticism because total depravity means that human reason, senses and desires are distorted by sin including the desires and attempts to have spiritual experiences. Calvin warned against mysticism to guard Christians against vain speculation, idle curiosity, and the sinful desire to go beyond the only sources of divine knowledge given to humans which are Christ, creation, and Scripture. Any genuine spiritual insights gained through Christ, creation and scripture must be an act of God’s grace effectuated by the Holy Spirit, not a result of a mystical connection by God utilizing innate human spiritual capacity.

Calvin did believe that mystery did exist in Christianity. He believed in the mystery of the union between believers and Christ and in the mystery of the presence of Christ in the eucharistic elements. Commenting on both the mystery of this union and its enactment in the Lord’s Supper, Calvin wrote, “We acknowledge that the sacred union that we have with Christ is incomprehensible to carnal sense. His joining us with him so as not only to instill his life into us, but to make us one with himself, we grant to be a mystery too sublime for our comprehension, except insofar as his words reveal it.” Calvin and orthodox (conservative) Protestants have not “…thrown all the mystery out,” they just put boundaries on the means and degree to which God reveals his presence and substance through mysticism and mystery.

Orthodox (conservative) Calvinists do agree with Charles Taylor’s three bulwarks of metaphysical realism. The question is can the bulwarks of metaphysical realism lead to a saving relationship with God? An orthodox Calvinist would say metaphysical realism only gets you part of the way.

An orthodox Calvinist believes in something called general revelation which states that God reveals His existence through His creation as stated a number of Psalms, and as stated by Paul in Romans 1: 18-22 which states that this general revelation is sufficient to reveal the existence of God and to humankind and for humankind to incur punishment from God if they reject His existence. The key question is whether or not this metaphysical realism is a sufficient means for individual humans to enter into a saving knowledge and relationship with God, and an orthodox Calvinist would say “no.” A saving relationship requires a next step beyond general revelation which is God’s intervention at a personal level to convince someone of their sins, the need for redemption and the acceptance through faith that Christ’s death on the cross provided that redemption and justification through penal substitutionary atonement. The Holy Spirit then works through the process of sanctification to make us, though imperfectly, more and more like Christ.

The current problem is that humankind has made God progressively less sovereign and smaller and smaller over the past 400 years. This in turn has reduced the ability of general revelation to lead people to conclude there must be a God. However, this is not the Calvin’s fault. Calvin, in particular, believed in a very big sovereign God who sustains and directs everything that happens in the universe including the direction of the individual droplets of spray coming off the prow of a speeding boat.

Don't blame Calvin. Blame Ockam who forgot that God is unchanging as well as sovereign. Blame Darwin who provided a non-Divine means to achieve the complexity, mechanisms and wonder of the natural world. Blame Freud who removed sin and guilt from the understanding of human behavior and hence the need for God and redemption. Blame Marx who shifted the focus of Christianity from God to the poor and under privileged (not necessarily a completely bad thing) and hence the need for God and redemption. Blame the historical criticism of 19th century German theologians who reduced the authority of God and the Bible. Blame post-modernism that gave sanction to the idea that one’s feelings and desires are the true bases of reality, authority, and self-definition and eliminates the need for God and religion in life.

Would the mysticism inherent in majestic cathedrals, the lives of the saints, icons, incense and ringing bells have preserved a big sovereign God over the past 400 years. I don’t think so. Humankind is fundamentally sinful and is always seeking ways to move away from God. I think the ideas of Darwin, Freud and Marx or their equivalents would have still happened.

Pardon me if my rationalist Calvinism is showing here, but metaphysical realism engenders emotions like awe and wonder. However, Christians whether Orthodox, Catholic or Protestant need to move beyond how their Christianity makes them feel and focus on the factual underpinnings of their faith and the implications of their faith to effectively apply Christianity in world. Emotional experience cannot be a foundation for belief, nor can it be the standard by which to judge truth, goodness, e.g. Belief and the standards by which we live a Christian life can only be based on a knowledge of the facts of salvation as presented in the Bible and the basic theological principles derived from these facts.

A final thought experiment. A fundamental characteristic of mysticism is that it is an emotional experience and touches something beyond our selves. However, both religious and non-religious experiences can engender a mystical feeling and a connection beyond our selves. How do we know what mystical experience is God revealing himself and what mystical experience is not from God.

For example, Voces 8 singing Danny Boy, --https://youtu.be/RorRJPhQfaM?si=0FW60gpLbwQS5u3f; Sydnie Christmas singing “Over the Rainbow -- https://youtu.be/GBgNKRw5BQ8?si=wWts62RlkRGWMiay; songs from the Orthodox Funeral Trisagion and Troparion -- https://youtu.be/TACo9ekOfas?si=G4oe5pYmnLiYqRNnT; and the Hymn of the Cherubim by Tchaikovsky -- https://youtu.be/KhbuNZ8p3hg?si=cPO5Zo-g_Zgim2aA all engender a mystical feeling of longing for and hoped connection to a better place beyond our current selves. However, which of these emotional longings for something or someplace outside ourselves is from God? Can we assume the mystical and emotional experiences engendered by songs from the Orthodox Funeral Trisagion and Tchaikovsky’ Hymn of the Cherubim are from God just because they have a religious theme?

Calvin would say we cannot reliably know because of humankind’s total depravity, and that is why and that is why he believed only nature (general revelation), Christ and Scripture were the only reliable means of Divine revelation. Calvin still believed in mystery, but not a reliable basis for a saving relationship with God.