Matthew Crawford In Budapest

Sunday Morning Cultural Jig With The 'Shop Class As Soulcraft' Philosopher

Have to share with y’all a special thing that happened this weekend. The US writer and philosopher Matthew Crawford — author of Shop Class As Soulcraft, The World Beyond Your Head, and Why We Drive — is in Budapest this weekend on his honeymoon. We had drinks and dinner last night, and this morning Matthew and his wife Marilyn went to church with me (he has recently become a Christian, thanks in part to the witness of his wife, an Anglican).

This meeting meant a lot to me as an admiring reader of Crawford’s work over the years. I draw on his World Beyond Your Head in my upcoming book Living In Wonder, which is now about two months from release (pre-order here for October 22 delivery). Matthew knows something about enchantment. Excerpts from Living In Wonder:

We normally pay attention to what we desire without thinking about whether our desires are good for us. But that is a dangerous trap in a culture where there are myriad powerful forces competing for our attention, trying to lure us into desiring the ideas, merchandise, or experiences they want to sell us.

Besides, late modern culture is one that has located the core of one’s identity in the desiring self—a self whose wants are thought to be beyond judgment. What you want to be, we are told, is who you are—and anybody who denies that is somehow attacking your identity, or so the world says. The old ideal that you should learn—through study, practice, and submission to authoritative tradition—to desire the right things has been cast aside. Who’s to say what the right things are, anyway? Only you, the autonomous choosing self, have the right to make those determinations. Anybody who says otherwise is a threat.

What does this have to do with enchantment? The philosopher Matthew Crawford writes that living in a world in which we are encouraged to embrace the freedom of following our own desires—which entails paying attention only to what interests us in a given moment—actually renders us impotent. He writes, “The paradox is that the idea of autonomy seems to work against the development and flourishing of any rich ecology of attention—the sort in which minds may become powerful and achieve genuine independence.”

We have allowed ourselves to believe that the world beyond our heads is nothing but representations to be constructed socially, politically, and psychologically. That it’s all just stuff with which we can do whatever we want. This is how the brain’s left hemisphere construes the world: as meaning-free material waiting for us to impress our thoughts and desires upon.

If you give yourself over to a mental framework that construes the world outside your head as nothing but a blank screen onto which you can project your wants and your will, you condemn yourself to living in a fantasy that can only make you miserable. It is a form of escapism that, in truth, traps you inside your head, in a world of chronic disenchantment.

So if you want to escape the waves and whirlpools of ungoverned passions, you have to search for still waters in the turbulent waters bounded by the shores of our skulls. Crawford’s big idea is to drop anchor in the real world. “External objects provide an attachment point for the mind; they pull us out of ourselves,” he says.[ii]

It sounds absurdly simple, but it’s still hard to do. Yet it works. Silently praying the Jesus Prayer according to my priest’s directions gave me at least one hour a day in which my mind was stilled and focused only on practicing the presence of God. The Jesus Prayer, about which we will learn more shortly, is not the only way, of course, but any method of prayer that fails to focus one’s attention rightly is doomed to fail.

More:

Our perceptual experience of the world is not just what we see and hear. The philosopher Crawford, who also works as a motorcycle mechanic, promotes the value of working with your hands as a way to connect viscerally with the real world and to learn how to resonate with it. He writes about the body as a means of perception, of knowing. There are some things about the world that we can know only through physical experience, particularly through the kind of disciplined, repeated experience that someone who apprentices himself to a master of the craft knows.

Practices build up things within so we can see and experience the really real. This is one lesson of Crawford’s practical philosophical work, and this was the lesson my years of intensely praying the Jesus Prayer taught me. Without knowing what was happening, the meditative prayer created within me a space of stillness where there had been none before—and, eventually, that oasis of calm spread through my mind and body, conquering the anxiety that made me so sick. As I told my priest later, I have always been the kind of person who believes that the answer to all my problems can be found in a book. But I learned that some problems can be solved only through doing.

I entered the Orthodox Church in 2006. Learning to be an Orthodox Christian has as much to do with the body as with the mind. If you’re doing it right, you fast in prescribed times and take up other practices shared by the community of believers around you, throughout the world, and in the church’s long history. The worship service is a highly choreographed liturgy filled with incense, candles, and chants; bowing, making the sign of the cross, and kissing icons. It doesn’t make a lot of sense at first, but after you get the hang of it, you realize that these practices are not just for aesthetic pleasure. They teach you. They guide your attention and shape your desires. They make you Orthodox.

It’s not that Orthodoxy offers a magical formula out of disenchantment. But it is the case that Orthodox Christianity is a highly embodied religion, the practice of which trains the believer who submits to its disciplines to pay attention to the really real—above all, to God.

Orthodox spiritual disciplines function as what Crawford calls a “cultural jig”—his term for the pattern of practices within a particular discipline that make it easier to progress in skill and knowledge. A jig is a tool that manufacturers use to hold materials in place so that they can guarantee the precision and accuracy of the finished product. The traditional liturgical and spiritual practices of the Orthodox Church are an example of a cultural jig—the kind of framework that keeps the individual believer in place and makes it more likely that he will be formed, over time, into a faithful and obedient Christian within the Eastern tradition.

Other Christian traditions also provide cultural jigs to guide the spiritual life, though many Americans from nondenominational and other low-church Protestant backgrounds seem to prefer a more spontaneous, less regularized approach to prayer. They resist prescribed prayers and liturgies and instead pray as the Spirit moves them. When it works, this style facilitates a personally intimate engagement with God that bears good fruit. But it can also veer off into directionless emotionalism and train one to pay attention to novelty and to seek emotional intensity in prayer at the expense of spiritual depth.

An established religious tradition’s cultural jig can also be a real gift in a time of pain and confusion. In the summer of 2015, my elderly father died in home hospice care after a long decline. Most of his family, and some of his friends, had gathered around his bed to accompany him to the end. After he took his last breath, and his lifeless body settled, everyone stood in stunned silence. What do you say in a moment like that? Though all of us had seen Dad’s death coming, incredibly none of us had thought about the kind of prayer or recitation that would be appropriate to mark the minute after his death.

Unless we had had a Shakespeare among us, there is nothing any of us could have come up with on the fly that would have been worthy of the gravity of that moment. Had someone offered a prayer that began “Lord, we just want to thank you . . . ,” it would surely have been sincerely given and warmly received by God and the others around my father’s deathbed. But the tense knot of loved ones gathered that August afternoon to be with Ray Dreher when he died had just watched the death agonies of a husband, father, grandfather, uncle, dear friend, and neighbor, a man who had been an intimate part of their lives for many years. Somehow, that kind of prayer would have diminished the meaning of what we had just seen.

Because years earlier I had embraced a liturgical Christian tradition, one that has a treasury of formal prayers, I was able to recite the Lord’s Prayer and a psalm from memory. The prescribed words and Scripture carried the weight of that tense minute or two for all of us, and allowed the mourners to focus on their thoughts about their beloved’s death. And they gave an air of dignity, sanctity, and, dare I say, enchantment to my father’s passage out of this life.

We all lived that afternoon through an example of Matthew Crawford’s teaching that practices allow us to see “the really real.” By speaking timeless words out of our faith’s holy book, words sanctified by generations and generations of use by believers in times such as this, and by directing the mourners’ attention in that way, the family and friends were able to touch the immensity of my father’s departure into the communion of saints and to know that we had all witnessed something profound.

The Crawfords are Anglican. Today was their first time at an Orthodox service. It has been so long since I looked at the Living In Wonder manuscript that I had forgotten until just now, after I said goodbye to them and came back home to search its pages, that its Crawford parts are tied to Orthodox spirituality.

Though Living In Wonder is a book by a Christian, told in a Christian key, I draw from different sources — not all of them theological — to help readers learn what enchantment is, and how to open oneself up to it. Crucially, you cannot compel yourself to be enchanted. This is one big difference between occult practice and Christian practice, a point I’m going to explore in my next Substack post (which will arrive later today, as I will be traveling all day tomorrow). All you can do is prepare yourself to receive that grace. It’s like the philosopher Elaine Scarry said about education. Education, she has it, is not the transmission of information, but rather training students to be staring at the right corner of the sky when a comet blazes past. So too with enchantment.

I’m really excited that we’re getting closer to the book’s release. If you wish to pre-order a copy of the hardcover signed by me, you can get it exclusively through Eighth Day Books.

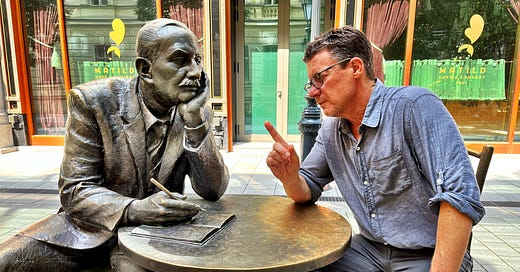

I encourage you to check out Matthew’s great Substack, Archedelia, to which I subscribe. Here is Self with Matthew and his new wife Marilyn, who is sunshine made flesh.

Now this is the stuff I really love! I can’t wait to get my hands on the book when it comes out.

If you want to meet people who really know, really grok (in Heinlein’s term) that following one’s desires is the path to perdition, may I suggest a visit to a 12-step meeting, Alcoholics Anonymous or one of its numerous offspring. There, you will meet people whose lives were absolutely destroyed by the desire for some substance (be it drugs or alcohol) or some other thing or activity (overeating, sex, gambling, codependency, what-have-you).

What a strange thing our brains can be! Desiring things we know will be unhealthy, even so simple a thing as not wanting to get out of bed in the morning! And yet we also know that the disciplines we put upon ourselves, those things we don’t want to do, like getting to the gym and exercising, are the very things that will make us happy! If intelligent design is a thing, whoever designed humanity had a perverse sense of humor.

Beyond that, have you noticed how our culture, and capitalism specifically, is rooted completely in this notion that true happiness is to be found in the satisfaction of desires? The whole point of marketing is to create desires where none previously existed and then to satisfy them. Social media is deliberately engineered to make you desire to watch that next video, to keep scrolling, even at the expense of your mental health. Heck, Doritos are engineered to make you desire to keep eating until you’ve gone through the entire bag, at the expense of an obesity epidemic. Once you recognize the pattern, you see it everywhere: an entire economy built on the lie that true happiness is right around the corner for the low, low price of $19.95.

There is something truly evil at the very core of our economic system.

I like the point about discipline as well. Or perhaps guardrails is another way to put it. One of my happiest times in my life was one of the most regimented, while I was in the Army. Was I frustrated by the limitations placed on me? You bet I was! But it turns out that those restrictions also did me and my mental health a lot of good.

It seems to me that a healthy society will eschew this constant drive for more, more, more and will build these guardrails up through many institutions, not just religious ones. Moreover, those limits must start with those at the very top. The masses won’t accept restrictions like these if they see the elites flouting them. This is the main reason Trump is such a disaster: the man never saw a desire that he could say no to and it shows. He’s the avatar of the sickness, not its cure. But of course the same applies to celebrities in their private jets and billionaires buying Hawaiian islands, no matter their political persuasion. We are ruled by people who can’t or won’t say no.

Great post, great stuff.

As to ritual. raised a Methodist and lately a Presbyterian, but I am always transported by the words of commendation from the burial rite in the Book of Common Prayer: Acknowledge, we humbly beseech thee, a sheep of thine own fold, a lamb of thine own flock, a sinner of thine own redeeming.