My Sunday With The Amber-Eyed Hare

A day in Ephrussi Vienna and the ever-present threat of totalitarian apocalypse

On Saturday, I was walking along the Ringstrasse in Vienna, when a plaque affixed to a huge building on my right caught my eyes. This was once the Palais Ephrussi, it said. My God, this is it — this is the family home from The Hare With Amber Eyes! I step back to photograph it:

That book is a memoir, by the British ceramicist Edmund de Waal, of the rise and fall of his ancestors, the Ephrussis, a Jewish banking family. It is told through the story of 264 netsuke (pron. “NET’skay”), miniature Japanese sculptures, usually in ivory or hard wood, that had come into the family’s possession in the 19th century. Charles Ephrussi, a scion of the family’s French branch, became a patron of the arts in the late 19th century, and a collector. He was at the center of the Parisian art world; Marcel Proust used him as a model for Swann in Remembrance Of Things Past. Charles was friends with all the Impressionists, many of whose paintings he acquired. Along the way, he bought hundreds of netsuke.

The Ephrussi were Jewish immigrants from Odessa who made their fortune there in grain trading, but became fabulously rich in Europe by becoming bankers. De Waal’s grandmother Elizabeth was descended from the Viennese branch of the family. Charles’s netsuke passed into the hands of the Viennese Ephrussi, and dwelled in the Palais Ephrussi, the family’s mansion. When the Nazis came to power in Austria through the 1938 Anschluss, the Ephrussi lost everything virtually overnight. Elizabeth, a lawyer, was already living in England, married to a Gentile Dutchman, Henrik de Waal. She worked tirelessly to get her parents and her younger brother Rudolf out before they were hauled off to a concentration camp. She succeeded, but both parents died before the end of the war.

After the Nazi defeat, Elizabeth returned to Vienna to see what had become of the family home where she had grown up. The Nazis had stripped it bare of its contents. Virtually the only thing that had come through the war were the netsuke, which a faithful Gentile maid, Anna, had secretly taken away under the eyes of the Gestapo, and hid in her mattress for the duration of the war. She returned them to Elizabeth when they met under the American occupation.

The Hare With Amber Eyes is a memoir of a family’s rise and hideous fall at the hands of Nazis and anti-Semitic collaborators, but it is also a riveting story about how material objects — from tiny sculptures to hulking mansions — come to possess imaginative power. As it happens, I’ve had a copy of the book in my Kindle library since 2012, two years after its release; I read it to learn how to write a memoir, before I began Little Way. I called it up on Saturday night, and resolved to re-read the Vienna sections while here in the Austrian capital.

The Vienna Ephrussi who built the family Palais was Ignace (Ignaz), who, in de Waal’s telling:

was a Gründer, a founding father, of the Gründerzeit, the founding age of Austrian modernity. He had come to Vienna with his parents and older brother Léon from Odessa. When the Danube flooded Vienna catastrophically in 1862, water lapping the altar steps of St Stephen’s Cathedral, it was the Ephrussi family who loaned money to the government for the construction of embankments and new bridges.

Somehow I imagine that it was Ignace who chose Hansen as architect; he understood how to make symbols work. What this rich Jewish banker wanted was a building to dramatise the ascendancy of his family, a house to sit alongside all these great institutions on the Ringstrasse.

Like so many Jews of that era, the Ephrussi were deeply assimilated. Ignace had been ennobled by the Kaiser for services to the crown. They never went to synagogue, and adored German culture. They believed in German civilization. Though the Kaiser, Franz Josef, had promulgated anti-Semitic policies early in his reign, in the immediate aftermath of the 1848 revolutions, by the end of his age, Franz Josef declared that his empire would not tolerate Jew-hatred, as Jews were the most loyal members of the Empire.

The Ephrussi of Vienna collected books, art, furniture — all the things you would expect fabulously wealthy, cultivated people of 19th century Vienna to accumulate. Ignace’s son Viktor was his heir, running the Ephrussi Bank in the city, and raising his children with his wife Emmy there in the Palais Ephrussi. Vienna had a large and thriving Jewish community. De Waal:

By the time of Viktor and Emmy’s marriage in 1899 there were 145,000 Jews in Vienna. By 1910 only Warsaw and Budapest had a larger Jewish population in Europe; only New York had a larger Jewish population in the world. And it was a population like no other. Many of the second generation of the new migrants had achieved remarkable things.

They had. They thought they were safe. Then came Hitler’s annexation of Austria in 1938, which was greeted by ecstatic crowds. De Waal:

The Cardinal of Vienna has ordered the bells of Austria to ring, and the bells of the Votivkirche opposite the Palais Ephrussi start pealing in the afternoon, and the noise of the Wehrmacht as it grinds round the Ring makes the house shake.

The Cardinal of Vienna proclaimed rejoicing the Austria had a Führer. Hitler was not imposed on the Austrians. De Waal quotes a Swiss newspaper report from the scene: ‘The scenes of infatuation at Hitler’s arrival defy description,’ writes the Neue Basler Zeitung.

Very quickly, life changed for the Jews of Vienna:

There is terror. People are picked up off the streets and bundled into trucks. Several thousand activists, Jews, troublemakers are sent to Dachau. In these first few days there are messages from friends who are leaving, desperate phone-calls about people who have been arrested. Emmy’s cousins Frank and Mitzi Wooster have left.

Their closest friends, the Gutmanns, have gone, leaving on the 13th. The Rothschilds have gone. Bernhardt Altmann, a business colleague of Viktor’s, a friend from countless dinner-parties, has left already: it takes something to walk out your door and leave everything.

… Jude is painted on Jewish-owned shops, and customers are targeted if they are seen going in or coming out. The huge Schiffmann department store, owned by four Jewish brothers, is systematically emptied by the SA as crowds look on.

… And all these things, a world of things – a family geography stretching from Odessa, from holidays in Petersburg, in Switzerland, in the South of France, Paris, Kövecses, London, everything – is gone through and noted down. Every object, every incident, is suspect. This is a scrutiny that every Jewish family in Vienna is undergoing.

Here de Waal notes what this means in agonizing detail:

And it not just their art, not just the bibelots, all the gilded stuff from tables and mantelpieces, but their clothes, Emmy’s winter coats, a crate of domestic china, a lamp, a bundle of umbrellas and walking-sticks. Everything that has taken decades to come into this house, settling in drawers and chests and vitrines and trunks, weddingpresents and birthday-presents and souvenirs, is now being carried out again. This is the strange undoing of a collection, of a house and of a family. It is the moment of fissure when grand things are taken and when family objects, known and handled and loved, become stuff.

I’ve written before about the great French film Summer Hours, which is about the same kind of thing, though not remotely in the context of historical trauma. It’s about family objects becoming “stuff” after the matriarch dies, but two of her three heirs have moved abroad, and cannot afford to maintain the house and the objects. That loss of meaning infused into household objects is a natural thing — sad, but that’s life. What was done to the Jews of Vienna is a rape and a murder.

De Waal:

So this is how it is to be done. It is clear that in the Ostmark, the eastern region of the Reich, objects are now to be handled with care. Every silver candlestick is to be weighed. Every fork and spoon is to be counted. Every vitrine is to be opened. The marks on the base of every porcelain figurine will be noted. A scholarly question mark is to be appended to a description of an Old Master drawing; the dimensions of a picture will be measured correctly. And while this is going on, their erstwhile owners are having their ribs broken and teeth knocked out.

Viktor and Emmy escape to Czechoslovakia. They were once among the wealthiest people in Europe, but on that day, they owned only what they could carry, and the family country house in the Czechoslovak countryside. Emmy dies there, likely a suicide. After Hitler annexes the Sudetenland, it is clear Viktor won’t be safe there. Elizabeth labors to get him to England. Note this passage; it will be important shortly:

On 1st March 1939 Viktor receives his visa, ‘Good for a Single Journey’, from British passport control in Prague. The same day Elisabeth and the boys leave Switzerland. They take the train to Calais and the ferry to Dover. On 4th March Viktor arrives at Croydon airport, south of London. Elisabeth is there to meet him and takes him to the St Ermin’s Hotel in Madeira Park, Tunbridge Wells, where Henk has booked rooms for them all. Viktor has one suitcase. He is wearing the same suit Elisabeth had seen him wear to the railway station in Vienna. She notices that on his watch-chain he still carries the key to the bookcase in the library in the Palais, the bookcase of his early printed books of history.

Yesterday, Sunday, after church, I had breakfast, read from the book, then decided to walk over to an antiques shop where I recall they sell netsuke. I admire the few they have in the window, and thought about the Ephrussi. Then I realized that I was only a few steps away from the Jewish Museum of Vienna. Why not go see?

It’s easy to find because even in this day and age, an armed guard has to stand there. There may well be Nazis about. But these days, the anti-Semites are more likely to be European Muslim fanatics.

I pay for my ticket, and lo, in the first room I enter, there are some of the Ephrussi family’s netsuke, including the famous hare (see my photo above). The museum displays them in what reminds me of an ark:

Here’s another photo, to give you perspective. All these intimate, intricate sculptures are about the size of a walnut.

Incredible. There they are. There is the hare. That is the object, the thread, connecting all who see it to the Ephrussi family, once one of Europe’s grandest, now, thanks to the Germans and the Austrians, disinherited and disintegrated.

Upstairs, I learn more about European anti-Semitism. It is a difficult thing for a believing Christian to deal with. The cruelty that generation upon generation of Christians visited upon these people of the Book is downright satanic. Look at this 19th century walking stick of a kind favored by Viennese Christian gentlemen:

Get it? Ha ha, the handle is a big Jew nose. The museum has several others of the genre. Hatred of Jews was so deep in the culture that you wonder how on earth Jews like the Ephrussi ever felt safe in that world. But they did. They thought that if they put their religion behind them, and adopted all the manners and tastes of Gentile society, they would be accepted. They thought pogroms and suchlike were a thing of the past.

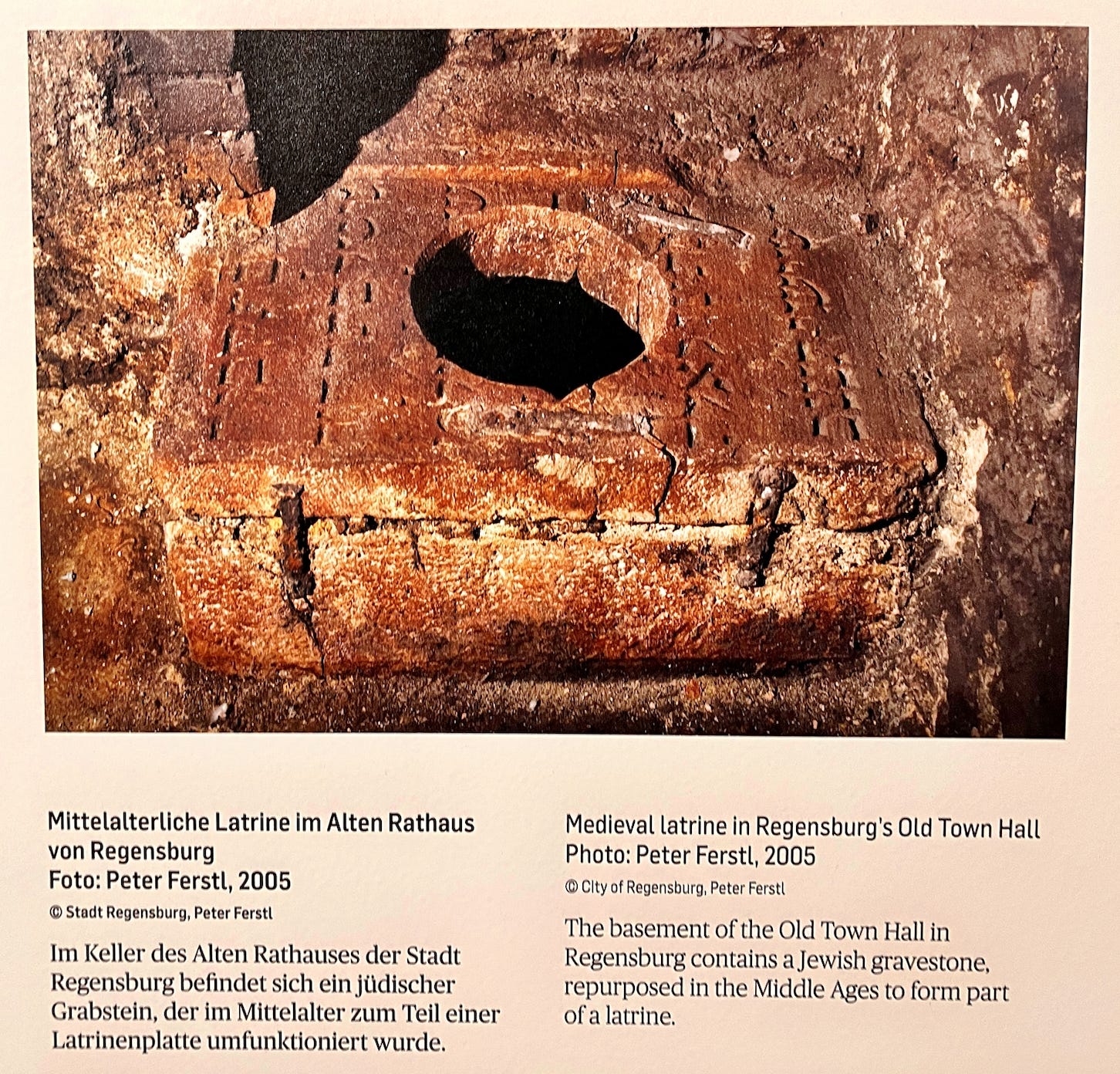

Look at what I saw in the part of the museum over at the Judenplatz, the heart of medieval Jewish Vienna:

In medieval Regensburg, in the town hall, the fine Christians of that city used a Jewish gravestone for a toilet. The mind reels. That same museum features this large key discovered in the 1990s in excavations at the Judenplatz that unearthed the remains of a medieval synagogue (the Jews were expelled three times in this city’s history). Nobody knows what it opened. It’s like Viktor’s key, seems to me:

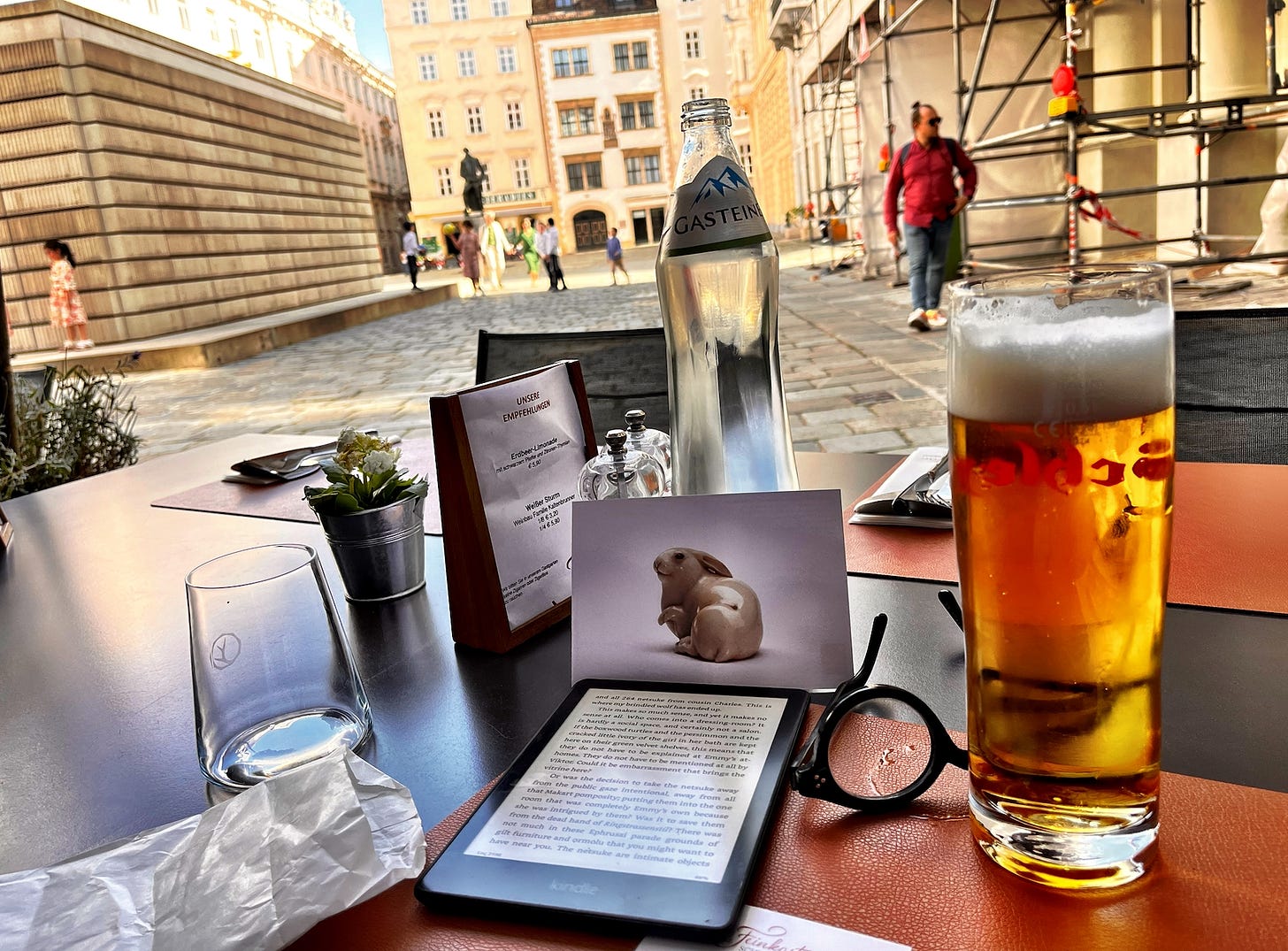

I took a table at a cafe on the Judenplatz, ordered a beer, and waited for my son Matt to join me for a late lunch. I observed Jewish children laughing and playing around the hideous memorial to the Viennese Jews murdered by the Nazis. The scene is so pregnant with meaning I nearly burst into tears:

Matt is delayed. I start reading The Hare With Amber Eyes again. Here is a sad and strange View From Your Table, featuring a postcard of the hare that I bought at the museum shop:

When Matt arrives, I tell him how ugly that memorial is, and how I think the murdered Jews deserved something better than that unsightly box, which ruins the plaza. No, says Matt, it ought to be ugly. People ought not to be able to see a harmonious plaza, not after what happened here. I think he’s wrong, aesthetically, but later, I discover that Simon Wiesenthal, who voted for this design, agreed entirely.

I tell Matt that my preoccupation with decline and fall probably goes back to my watching the 1978 television miniseries Holocaust. I was eleven, and a budding history buff. I had no idea what the Holocaust was. Do you know we are the same distance from the first Bush administration today as America was from the 1945 discovery of the Holocaust back then? I remember lying on the floor of our family living room, my left cheek pressed against the green shag carpet, watching with mounting horror what the Nazis were doing to Jews of 1938 Germany. And then they lined up naked Jews in front of a ditch, and mowed them down with machine guns. I started sobbing and shaking. My father scooped me up and took me to bed. That was the end of my watching that series. But the trauma struck deep. I have never, ever been able to escape the idea that you think all is well, then boom, everything changes. Everything.

To be enchanted is to dwell in a liminal space between ordinary material reality and the transcendent, the eternal, the numinous. To be enchanted is to experience the feeling that there is somehow more to the person, place, or thing than what we can experience with our senses. It is somehow a gateway to the transcendent realm. What would you call, then, the sense you get when you are in that space, and know that it can be seized violently from you, and never restored?

What the Nazi totalitarians did to the Jews, in terms of stealing their property, the Communists did to the peoples that they cancelled. An older Hungarian man told me once that many villas in the fancy parts of the Buda hills, overlooking the Danube, are filled with the descendants of Communist officials who stole them from their rightful owners. If it happened once, it can happen again, if we are not vigilant.

We are in the final fundraising days of the Live Not By Lies docuseries project. I’ll be recording something today with Dave Rubin, and I’ll be talking about totalitarianism, and the hare with amber eyes, as well as what the Communists did to those they declared to be vermin. Tonight’s livestream will go from 7 to 8 pm Eastern; click on the link above to tune in. If this work of mine has ever moved you, I urge you to get involved — make an investment so we can make this documentary to warn the world.

Last week in Bratislava, Kamila Bendova told me that every week, she goes to a new funeral of a Charter 77 member, the anti-totalitarian human rights organization she co-founded in Communist Czechoslovakia. We don’t have a lot of time left to get these testimonies onto film, to warn the world about what can easily happen if we don’t stand firm, with clear eyes and strong wills. We need you to step up now, if you can. The safe world that the Ephrussi lived in here in Vienna fell apart seemingly overnight. Others in the Communist world had something similar happen to them. Solzhenitsyn warned that what happened in Russia could happen anywhere else on earth, under the right circumstances. So could what happened in the Reich. The skull is always just beneath the skin. The most important lie to refuse right now is the one that tells you it can’t happen here!

This already happened recently in New Zealand. A certain class of people could not work, use public services. or travel. It was for health reasons but people were also put in camps, then later hotels.

That Jewish gravestone as a latrine lid is something I don't have a word for. What an emblem of the hatred. And the head on the walking stick. Geez. I don't think reading about them would have nearly the same impact as seeing them, even just in a picture.