Oikophobia And The Hurricane

Why Does Washington Seem To Care More About Foreigners Than Americans?

Welp, looks like FEMA doesn’t have enough money to help Americans suffering through the hurricane season. From the NYT:

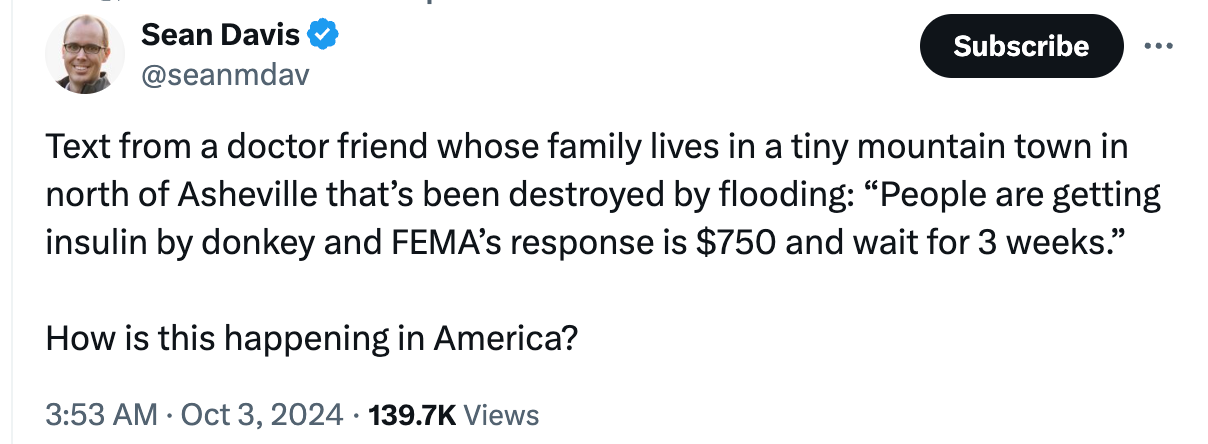

The announcement comes as FEMA is conducting search-and rescue-operations in remote sections of Appalachia six days after Hurricane Helene made landfall in Florida and moved north, causing widespread destruction and the deaths of at least 183 people across six states. President Biden has in recent days approved major-disaster declarations for the states affected by the storm.

“We are meeting the immediate needs with the money that we have,” Mr. Mayorkas told reporters on Wednesday while en route to meet with officials in South Carolina. “We are expecting another hurricane hitting — we do not have the funds, FEMA does not have the funds, to make it through the season.”

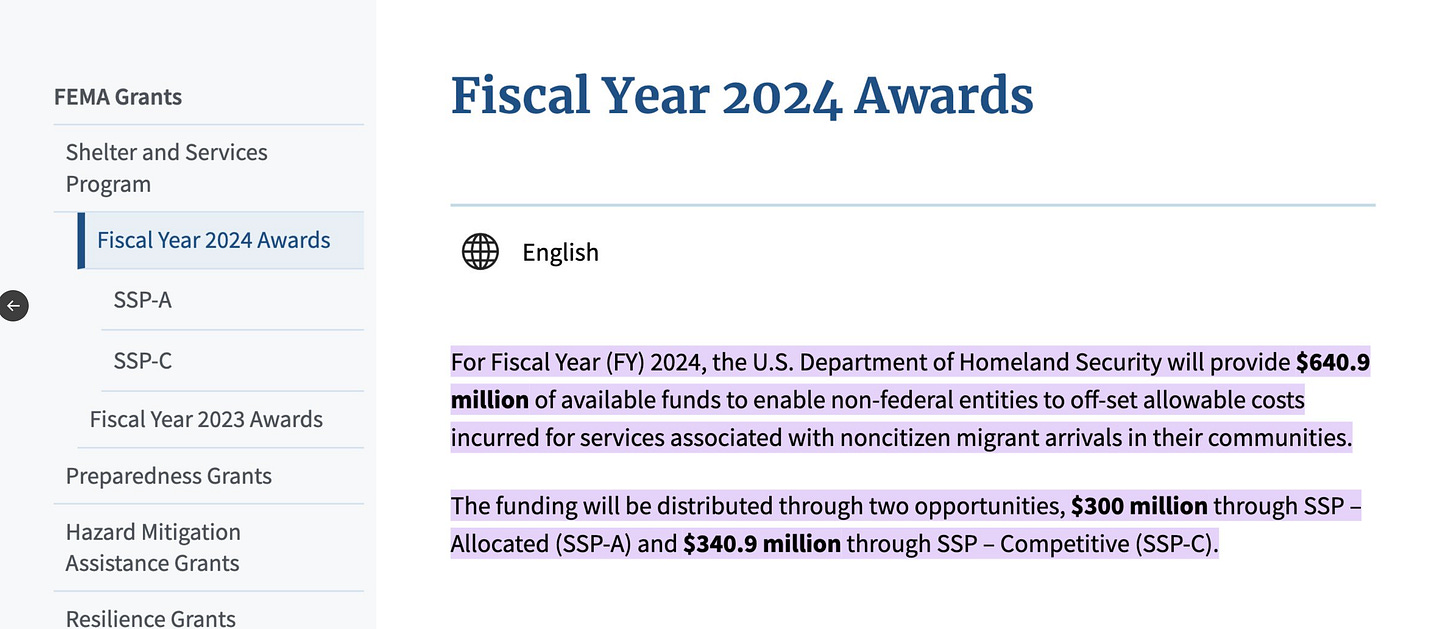

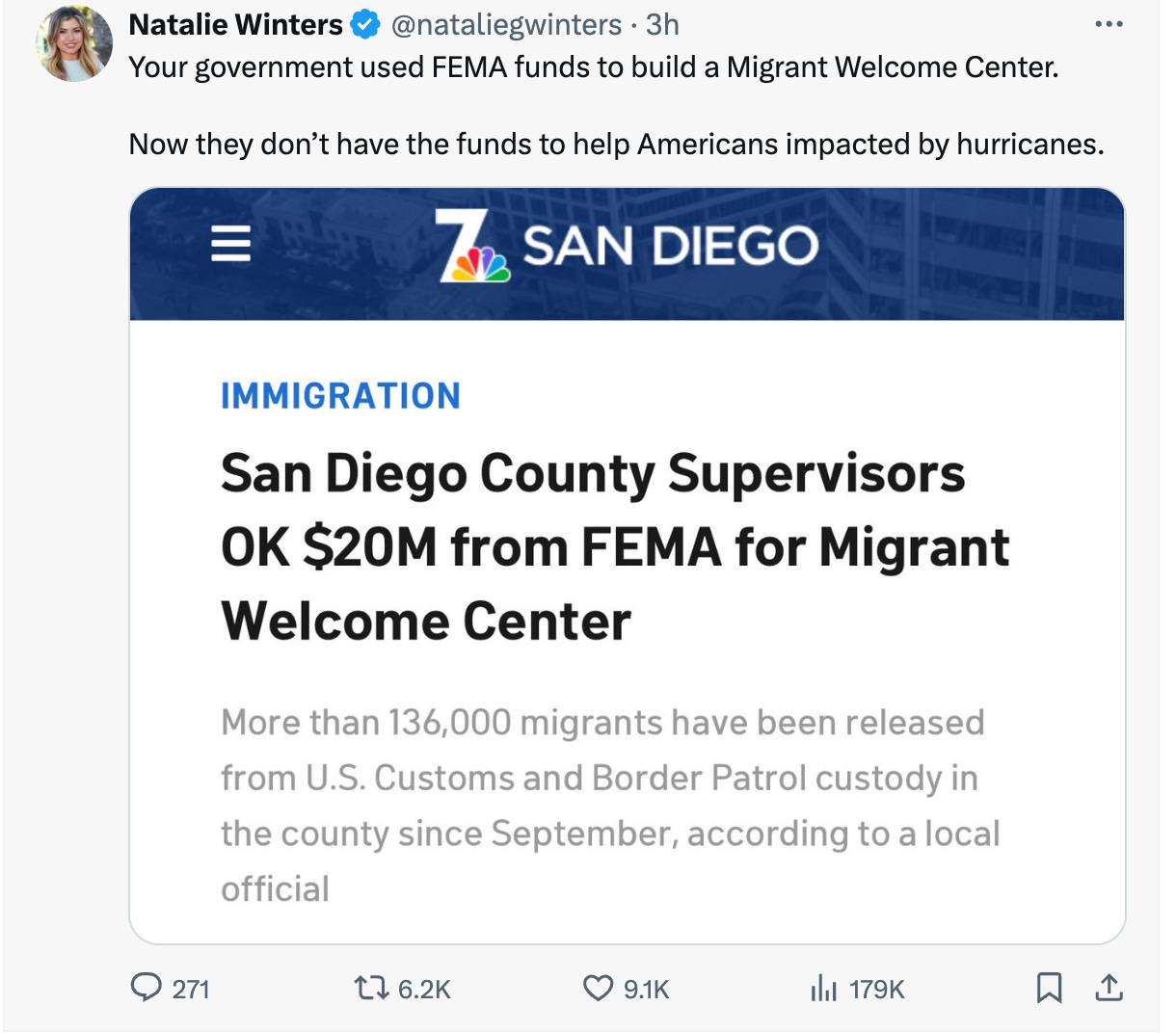

Where did all that money go? Park MacDougald shows us:

They spent $641 million on illegal migrants! This, even though we have hurricanes every year. But this is how our woke federal government rolls. From August 2023:

You will recall that FEMA believes racialism is foundational to (checks notes) emergency management:

And:

What the hell? Who are these ghouls in Washington? Oikophobia is a word used by Sir Roger Scruton to describe the hatred ruling class people have for their own kind. Wonder how much of that is in play in this situation. I don’t think it’s a matter of this administration not caring about parts of America that might vote Democratic as much as it is of them not seeing ordinary Americans, versus their capaciousness in caring about the Other. In 2022, Kamala Harris, talking about Hurricane Ian, endorsed applying the concept of “equity” to disaster relief — meaning that distressed white people need to take a back seat to people of color when it comes to receiving help. Western North Carolina is the whitest part of the state. Do I think the Biden-Harris administration is deliberately dragging its feet on helping those people? Absent further information, no, I don’t. but Harris’s 2022 remarks invite that interpretation.

I have a feeling that there is a hell of a story to be told about what is happening — and not happening — now in the hurricane-hit areas of Appalachia. Look at this amazing tweet by someone who is flying in supplies to stranded people who are signaling for help using mirrors. And check out this testimony from a man who says he doesn’t know why the feds aren’t allowing those bringing help to access stricken areas of North Carolina, but his experience trying to bring disaster relief to the hurricane-hit Florida Keys may be relevant. Excerpt:

It was 87 miles by water to get to our first stop, Cudjoe Key and Sugarloaf Key. When we arrived there we were greeted by a homeowner (for privacy, I won't name him, though we have video) who was elated to see us and all the supplies we brought, his house was in shambles.

We started offloading supplies on the shoreline and helping to get them into what was left of his house. During that process, he explained to us that FEMA had set up a command center at a local high school on the island, but that they weren't doing anything to help the residents, not even bringing them WATER! Instead, he explained that they were driving around using a loudspeaker, telling people to stay in their homes. They weren't even helping the home owners with supplies.

I was skeptical at first while he was telling me all of this, but then he said something that broke my heart.... He told us that the people of the keys were all in despair, because they had just seen, weeks before, the overwhelming support for Texas with Hurricane Harvey, by the citizens of this country. He, and his neighbors on all of the keys, felt like Americans had forgotten about them completely, because at this point, FIVE DAYS after landfall, all they had seen was FEMA, and they were of NO HELP.

The residents were cut off from the outside world, no cellular, no internet, no way to contact anyone or hear of any efforts to try to help them. The ONLY communication they had was from a local radio station on Sugarloaf Key, that was broadcasting on AM to the surrounding keys.

The man, after hearing that there were citizens trying to bring them help, but being refused entry by federal law enforcement was visibly upset. He, and his neighbors, really thought the country had abandoned them. He insisted that we get into his waterlogged truck and that he would take us to that radio station so that we could go live on air, to tell the citizens trapped in the Keys that we, the American people, were there to help and that the government was trying to stop our efforts. And that is exactly what we did.

Turns out state and local officials on the scene welcomed the relief. So why weren’t the feds letting it through? According to this man, Ryan Tyre:

I was able to coordinate several trucks full of supplies to be brought down to the EOC in Marathon. I was privy to the EOC meeting, BUT was informed in that meeting, that all of the semi trucks full of food, water and hygiene supplies were to be turned around and not allowed to be offloaded for distribution by the EOC.

THE REASON they gave us, was that these donations were not from companies on their "preferred vendors list" and that they would not accept them or give them to the residents of the keys impacted by the storm. It was at that point that I realized, this is ALL ABOUT MONEY.

These 'preferred vendors" are getting part of the money being released by the state and federal govt for each disaster. In turn, some of the "vendors" make it on the list because a friend gets them on the list, and in return for getting ridiculously outlandish amounts of compensation for the services they render, they give kickbacks.

So accepting outside donations, even though they are on location and can help people NOW, they would rather let people suffer so they can get their kickbacks.

This just came in, since I started writing:

I know this is a political season, and that folks are eager to politicize things like disasters. But sometimes things need to be politicized! In a democracy, when the government fails to do what it ought to be doing, then those who run it should be held accountable. It is not Washington’s fault that a terrible hurricane struck that region. But it verifiably is Washington’s fault that it spent all its relief budget on illegal migrants. It is Washington’s fault that those shithead bureaucrats spend time and money on making emergency responders ideologically compliant with wokeness, as opposed to effective at their jobs. And if those allegations of bureaucratic policies that keep citizens bringing aid out can be verified, then hell yeah, hold Washington responsible.

That means Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, who run the executive branch now.

Call me cynical, but I don’t expect the US media to make much effort to expose government incompetence and bad policy with relation to the Appalachian disaster. Telling the truth might help the Trump campaign. Yeah, I know: what if the feds aren’t actually guilty of behaving as badly as it seems, and what if journalists can establish that as fact? Would I have set up an epistemic barrier to accepting truth that runs counter to what I already believe?

Yes, I would have done exactly that. But this is the cost of having lost faith in the integrity of professional journalism in our era. Just the other night, we watched CBS News debate moderators avoid asking J.D. Vance and Tim Walz questions about pressing, indeed urgent, issues on which the Democrats are vulnerable (e.g., Ukraine, DEI, trans vs women’s rights). Am I really supposed to believe that the media are going to do a creditable job, one month before election day, exposing facts that stand to hurt the Democratic presidential candidate?

I don’t like being so cynical. But I didn’t fall off a turnip truck, and neither did you.

Ta-Nehisi Coates Is Back In Black

‘Memba that guy? He was one of the greatest grifters of the High Woke period. His memoir Between The World And Me was treated by the media as if it had been given to Coates on top of Sinai. Coates is an anti-white racist hack, but he was once a talented and searching writer — before he surrendered to racial despair. You can’t deny that he has been a highly influential writer too; even though he’s turned into a hack, he is thought to be a Very Serious Thinker by most of the media and academic elite.

Not Coleman Hughes, a fellow black writer who has Coates’s number. Hughes eviscerates Coates new essay collection as lazy, bigoted, left-wing hackery. From the review:

Here’s the crucial test of that metric: If you read nothing about a subject other than this author’s work, how informed would you be? To what degree would you understand the big picture?

On that metric, Coates fails spectacularly. Because Coates is not a journalist so much as a composer—one who uses words not to convey the truth, much less to point a constructive path forward, but to create a mood, the same way that a film scorer uses notes. And the specter haunting this book, and indeed all of his work, is the crudest version of identity politics in which everything—wealth disparity, American history, our education system, and the long-standing conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors—are reduced to a childlike story in which the “victims” can do no wrong (and have no agency) and the “villains” can do no right (and are all-powerful).

Take, for instance, his second essay, “On Pharaohs.” Beginning as an account of his trip to Senegal, the essay becomes a meditation on the relationship between Africans and African Americans—as well as the relationship of both groups to their ongoing “oppressor”: the West.

The essay relies, for emotional weight, on Coates’s assumption that Western nations are rich, and African nations are poor, because of colonialism. This framework makes the West morally responsible for the poverty of countries like Senegal.

But economists have long exposed the problems with this theory. For starters, five-hundred years ago, the whole world was poor. Wealth was created only when certain nations began to adopt a set of key institutions: property rights, honest government, markets, rule of law, and political stability. These institutions rewarded productivity and, in particular, innovation. Every nation that has adopted these institutions has grown exponentially as a result. Every nation that hasn’t has remained in the default state of poverty.

One of the virtues of this theory is that, unlike Coates’s theory, it actually explains the world around us.

Hughes zeroes in on what makes Coates Thought what it is: the simplistic idea that Whites Bad, Non-Whites Good. Coates brings that frame to analyzing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Hughes:

It quickly becomes clear, however, that acknowledging the Holocaust is but a throat-clearing exercise before the main event: over one-hundred pages of the most shamelessly one-sided summary of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict I have ever read.

To tell that story—and it is very much a story, not a history—Coates takes us back.

Not to the establishment of the Jewish state, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, or the First Zionist Congress but to his childhood in Baltimore. He recalls that he had “a vague notion of Israel as a country that was doing something deeply unfair to the Palestinian people, though I was not clear on exactly what.” He remembers “watching World News Tonight with [his] father, and deriving from him a dull sense that the Israelis were ‘white’ and the Palestinians were ‘Black,’ which is to say that the former were the oppressors and the latter the oppressed.” He recalls his father giving him a book called Born Palestinian, Born Black and appreciating that title.

In other words, Coates inherited an anti-Israel bias—based on crude, inaccurate analogies to American racial politics—on father’s knee. (His father ran an unsuccessful publishing house called Black Classic Press, which “took food off our table,” as Coates writes in The Beautiful Struggle, but was “another tool Dad enlisted to make us into the living manifestations of all that he believed and get us through.” Coates’s father recently republished The Jewish Onslaught, an antisemitic screed about Jews and the transatlantic slave trade.)

The younger Coates carried that homegrown bias through to adulthood, including well into his journalism career. You might expect a writer who routinely attacks white people who never question their childhood biases on race to wrestle, if only for a moment, with the possibility that his own inherited understanding might be clouding his judgment. But that moment never comes.

The fact that Ta-Nehisi Coates became a major, influential intellectual during the Great Awokening tells us a lot about what those years really meant.

Here’s Coates being interviewed on CBS This Morning about his new book.

One of the hosts asks him a hard question about the fairness and accuracy of his characterization of Israel. Coates gets indignant, and rather than address the complaint, falls back on asserting that he has a responsibility to be the voice for the voiceless. Wait a minute, though! Sure, be a voice for the voiceless, but that wasn’t the question. The question was about the fairness and accuracy of the story Coates tells, not his moral right to focus his attention on the Palestinians. Grifter, to the marrow.

Americans: Distracted And Illiterate

Did you know that we are raising a generation that doesn’t know how to read? It’s not because they don’t know how to process words (though there is some of that). It’s that they lack the attention to sustain focus. From The Atlantic:

Nicholas Dames has taught Literature Humanities, Columbia University’s required great-books course, since 1998. He loves the job, but it has changed. Over the past decade, students have become overwhelmed by the reading. College kids have never read everything they’re assigned, of course, but this feels different. Dames’s students now seem bewildered by the thought of finishing multiple books a semester. His colleagues have noticed the same problem. Many students no longer arrive at college—even at highly selective, elite colleges—prepared to read books.

This development puzzled Dames until one day during the fall 2022 semester, when a first-year student came to his office hours to share how challenging she had found the early assignments. Lit Hum often requires students to read a book, sometimes a very long and dense one, in just a week or two. But the student told Dames that, at her public high school, she had never been required to read an entire book. She had been assigned excerpts, poetry, and news articles, but not a single book cover to cover.

“My jaw dropped,” Dames told me. The anecdote helped explain the change he was seeing in his students: It’s not that they don’t want to do the reading. It’s that they don’t know how. Middle and high schools have stopped asking them to.

More:

No comprehensive data exist on this trend, but the majority of the 33 professors I spoke with relayed similar experiences. Many had discussed the change at faculty meetings and in conversations with fellow instructors. Anthony Grafton, a Princeton historian, said his students arrive on campus with a narrower vocabulary and less understanding of language than they used to have. There are always students who “read insightfully and easily and write beautifully,” he said, “but they are now more exceptions.” Jack Chen, a Chinese-literature professor at the University of Virginia, finds his students “shutting down” when confronted with ideas they don’t understand; they’re less able to persist through a challenging text than they used to be. Daniel Shore, the chair of Georgetown’s English department, told me that his students have trouble staying focused on even a sonnet.

The culprit here is smartphones (and the Internet), of course. It has done this to all of us. Me too. I am struggling to get through Mann’s The Magic Mountain, not because the book is dull (it’s not), but because I have a thousand other things competing for my attention, and struggle to focus on a long novel. It has been like that for me since around the start of this century, when I began to immerse myself in the Internet.

In Living In Wonder — out in fewer than three weeks, woo-hoo! — I write about how attention is vital to developing the capacity to experience God. Excerpts:

Our brains were not made to function with internet technology. It renders the task of understanding what we perceive much more difficult. Writes Carr, “It takes patience and concentration to evaluate new information—to gauge its accuracy, to weigh its relevance and work, to put it into context—and the internet, by design, subverts patience and concentration. When the brain is overloaded by stimuli, as it usually is when we’re peering into a network-connected computer screen, attention splinters, thinking becomes superficial, and memory suffers. We become less reflective and more impulsive. Far from enhancing human intelligence . . . the internet degrades it.”

It’s not just the internet but the ubiquitous way most of us access it: through the smartphone. Neuroscientists have found that the constant bombardment of information coming through the black-mirrored devices blitzes the prefrontal cortex, where most of our reasoning, self-control, problem-solving, and ability to plan takes place. The brain’s overwhelmed frontal lobes wind down higher-order cognition and defer to its emotional centers, which spark a cascade of stress and pleasure hormones.

Because the internet produces exactly the kind of stimuli that quickly and effectively rewire the brain, Carr says that it “may well be the single most powerful mind-altering technology that has ever come into use.”

Fine, but why is it a disenchantment machine? Because the internet destroys our ability to focus attention. The unruly crowd of competing messages jostling for the attention of our prefrontal cortex not only makes it harder for our brains to focus but also renders it far more difficult for us to form memories. This is because, for lasting memories to lodge in our minds, we need to process the information with sustained attention. Using the internet creates brains that cannot easily remember. As we will see later in this book, it also creates brains that cannot easily pray, which is the main and most important way we establish a living connection to God.

More:

It turns out that attention—what we pay attention to, and how we attend—is the most important part of the mindset needed for re-enchantment. And prayer is the most important part of the most important part.

It’s like this: if enchantment involves establishing a meaningful, reciprocal, and resonant connection with God and creation, then to sequester ourselves in the self-exile of abstraction is to be the authors of our own alienation. Faith, then, has as much to do with the way we pay attention to the world as it does with the theological propositions we affirm.

“Attention changes the world,” says Iain McGilchrist. “How you attend to it changes what it is you find there. What you find then governs the kind of attention you will think it appropriate to pay in the future. And so it is that the world you recognize (which will not be exactly the same as my world) is ‘firmed up’—and brought into being.”

We normally pay attention to what we desire without thinking about whether our desires are good for us. But that is a dangerous trap in a culture where there are myriad powerful forces competing for our attention, trying to lure us into desiring the ideas, merchandise, or experiences they want to sell us.

Besides, late modern culture is one that has located the core of one’s identity in the desiring self—a self whose wants are thought to be beyond judgment. What you want to be, we are told, is who you are—and anybody who denies that is somehow attacking your identity, or so the world says. The old ideal that you should learn—through study, practice, and submission to authoritative tradition—to desire the right things has been cast aside. Who’s to say what the right things are, anyway? Only you, the autonomous choosing self, have the right to make those determinations. Anybody who says otherwise is a threat.

What does this have to do with enchantment? The philosopher Matthew Crawford writes that living in a world in which we are encouraged to embrace the freedom of following our own desires—which entails paying attention only to what interests us in a given moment—actually renders us impotent. He writes, “The paradox is that the idea of autonomy seems to work against the development and flourishing of any rich ecology of attention—the sort in which minds may become powerful and achieve genuine independence.”

According to that Atlantic piece, the problem with students is not only a matter of the inability to focus. It’s also because schools have stopped demanding that the read entire books. Related, probably, but when I was in the US recently, I had a conversation with a man who told me that his local public school district is one of the best in his state, but that he had recently learned, through a situation involving one of his grandchildren, that the schools there no longer fail anybody. No matter how poorly you perform, you will be passed to the next grade. “Social promotion” we used to call it when I was a kid. It was thought to be a bad thing back then. Now, everybody gets a trophy, I guess.

It’s like American life has become a factory system in which the goal is to make as many widgets as fast as you can, and then find whatever you can to distract yourself from the meaninglessness of widget-making. The green light on Daisy’s dock shines in the darkness, but what lies beyond it? Does anyone even care? Or is it just go?

Kingsnorth Coming To Alabama

Last note today, before I head to Madrid to speak at a conference: here’s a link to Matt Burford’s interview with Paul Kingsnorth, in advance of our big weekend in Birmingham, Alabama, this month. Get info and tickets here! Gonna be a great time.

I am a physician on a Disaster Medical Assistance Team (Georgia), and I can attest that there never seem to be any funds.. We work under the auspices of HHS, not FEMA, but the bureaucracy is the same. I had to buy my own uniform as there was no money available for the government to provide official clothing. Our annual national conference was severely curtailed due to lack of funds, and on our monthly conference calls, the lack of money available for emergencies is a frequent topic.

Good luck America!

"Why Does Washington Seem To Care More About Foreigners Than Americans?"

Rod My Brother,

Most people I talk to are pissed off about this. We have a government that has billions for Ukraine and billions for Israel and billions for illegal immigrants, but when it comes to American people in times of hardship they could give a shit. That means they're stealing from us, our children and grandchildren (or future grandchildren) to line their own pockets with donations and kickbacks and insider trading tips, using our money to fund their pet projects and telling us the American Citizen to go pound sand. No wonder they want to get rid of the First Amendment and the Second Amendment. They want us disarmed and muzzled with a stasi like DOJ that will send Jack booted thugs in the middle of the night to kick down your door and gun you down in front of your wife and kids with a no knock warrant issued by some second rate, half wit lawyer in a black robe.

That's todays upside down America. They (the Ruling Class who pull the strings known as the Deep State) don't give a shit about us. To them We The People are a threat to their power and are to be treated as the enemy. This has become overwhelmingly apparent especially over the last decade. Our government is the biggest threat to American Freedom and Liberty not Russia or China or Iran. We need to wake up and take notice and prepare for whatever these bastards do next.