O.J.'s Legacy

And: Orthodoxy & Geopolitics; Goodbye, Church Ladies; The War We Are Conjuring

Even in an age of media spectacle, it is difficult to explain to people too young to remember it what a massive event the O.J. Simpson saga was. If you were anywhere near a television on the night O.J. fled through the highways of Los Angeles in Al Cowlings’ white Bronco, you remember where you were, who you were with, and the whole dang, this is really happening sense of the thing. You probably also remember the verdict in his murder trial, the most sensational since the Manson affair. When news broke yesterday of O.J.’s death (nobody called him “Simpson”), somebody on Twitter said that it was that verdict that revealed the racial chasm in America, almost twenty years before Black Lives Matter. Makes sense to me.

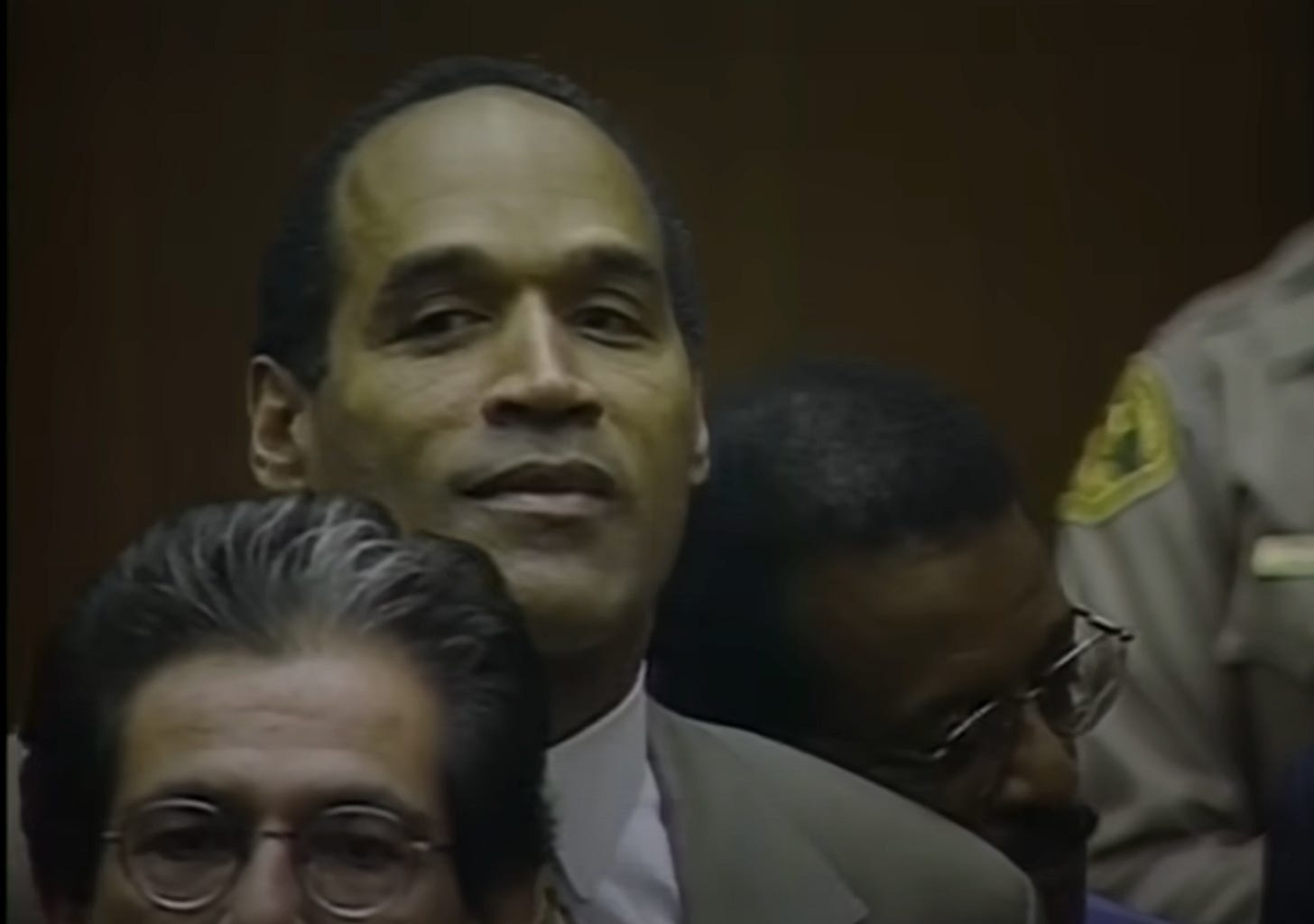

You have to recall what a positive, even beloved, figure O.J. was in popular culture prior to the murders. Nobody who first heard of him post-murder can imagine him as defined by anything but that, but boy, was he a big deal in the Seventies and Eighties. He was a football legend who went on to be a sometime movie actor, TV sports commentator, and advertising pitchman. Look:

This was one facet of O.J.’s pre-murder personality: the genial running back who leaped and bounded through airports to get to his rental car. The nice-guy persona you see in that commercial? That was O.J. Simpson in America’s eyes, for a very long time.

I saw him once, in January 1992. I was in New York City for business, and was headed afterward to France to visit friends. I worried that my winter coat wasn’t sufficient for conditions in the French Alps, so I went to Bloomingdale’s to see what they had on sale. There, in the overcoats section, I saw O.J. come in, with Nicole on one arm and her sister Denise on the other. I didn’t know who the women were (later, when he killed Nicole, and Denise became a fixture on television, I realized who they were), but I certainly knew O.J. The women were laughing, and O.J. had that happy-go-lucky look you see in the Hertz ad above. Cool, I thought. That’s O.J. Simpson.

Nobody could look on O.J. Simpson back then without pleasure. Everybody liked O.J.

Which is why the murders, and the special savagery of the murders, were such a collective shock. But not as big a shock as O.J.’s acquittal by the jury. It was widely observed at the time that white America was dumbfounded and disgusted, while black America was delighted. It wasn’t because black America believed O.J. was innocent, necessarily. It was payback. An O.J. juror — a black woman — said in a later interview that “90 percent” of the jurors believed O.J. was guilty, but they voted to acquit to pay white people back. Click here to watch the clip:

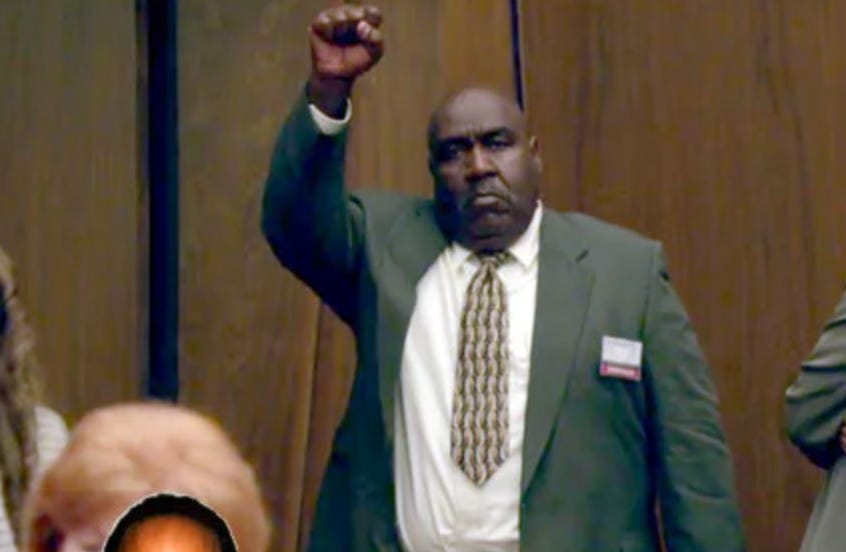

Juror Lon Cryer, who is black, gave Simpson the black power salute as he left the courtroom that day.

To be fair, it emerged in trial that the LAPD tampered with crime scene evidence. But the accumulation of evidence pointing to Simpson’s guilt was overwhelming. They mostly black jury let him off anyway because, according to the juror in the clip above, it was payback.

Maybe black readers of this newsletter remember it differently — and if so, I encourage you to share your memories. For me, it was the moment the Narrative that I had in my head about race and justice died. I was no longer a liberal in the mid-1990s, at the time of the verdict, but on issues of race, I was still pretty liberal, certainly for a white man from the Deep South.

I believed (and still believe) that Dr. King was an American hero. The more important point was that I had been acculturated according to the To Kill A Mockingbird narrative, which told us that in the bad old days, black people were railroaded by a racist justice system, but that was pretty much behind us now. It’s not that all trials were now free of racial bias — the world of perfect justice is not possible — but rather that we had come so far in refining our justice system, so that it was far less likely that verdicts came down according to the race of the defendant.

See, I had by then learned a horrible story about something that happened in my town back in the 1940s: an old white man known to my family had confessed on his deathbed that he had been part of a lynching party, organized by the sheriff, that tracked, captured, and hanged a black man caught having sex with a white woman. After the man’s murder, the white woman confessed that they have been lovers, and she accused him of rape after they were discovered, to save herself. No white person ever had to answer for that crime.

I knew the old man somewhat, and respected him. That he confessed to this crime in his final days on earth — my mom knew the person to whom he confessed — was a terrific shock. Incidentally, when I moved back to my hometown in 2012, I had the idea that I wanted to get to the bottom of it, to tell the story for the sake of the black man’s family, and justice. But I did not know the black man’s name, and had no idea where to turn. I asked a few black people in town that I knew if they had any knowledge of the murder. Either they didn’t, or didn’t want to talk to a white man about it, even after all these years.

I had been warned by a white liberal friend who had worked on a Civil Rights oral history project in the early 2000s that it is still very difficult to get local black folks who had lived through that period, when the KKK (whose number, I was grieved to learn a couple of years ago, probably included my own father) ran rampant — that it was hard to get them to talk to whites about what happened. I found this so hard to accept, because the evil of those days seemed to be long gone. Nevertheless, it is a sign of how traumatizing and dangerous those days were, that the blacks who lived through it are still reluctant to speak of it.

Anyway, in my mind back then, black folks were almost always the Innocent Victims, and they only wanted justice — real justice. I don’t want to overstate this; obviously I knew that black criminality was a real thing, and that blacks are human beings who can be just as guilty, or just as innocent, as whites. The point is that I had this idea that all decent people wanted not verdicts that confirmed their biases, but rather justice. The idea that a black jury could exonerate a black murderer of whites who was obviously guilty, and to do so as a sign of racial solidarity, was extremely hard for me to accept.

That is to say, it was a shock to my system to grasp that black people were just as capable of being rotten racists who don’t care about the lives of people of other races as white people were. I laugh now at my naivete, but that’s how it was.

We tend to think that the 2012 Trayvon Martin killing, and the not guilty verdict against George Zimmerman — the event that birthed Black Lives Matter — was the turning point that poisoned race relations in America. Or maybe the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., which was judged to have been justified (a conclusion backed up by an Obama Justice Department investigation), on account of Brown was a criminal who tried to grab the officer’s gun. Some black witnesses said that Brown held his hands high and said, “Don’t shoot,” but hard evidence proved otherwise.

It seems clear in retrospect that the O.J. verdict was the real turning point. To see not only the verdict, but the way so many black Americans openly celebrated it — man, what a redpill moment. You can understand why it felt that way to black people, given the horrendous history of the American justice system. Nevertheless, two people died in a savage knife attack, and it seemed overwhelmingly likely that O.J. Simpson did it. To see so many black Americans not care about whether he was truly guilty of the crime, and to celebrate his acquittal as payback — well, look, if you were raised on the post-Civil Rights era story, you didn’t think such a thing could happen.

Let me be clear: it’s not the case that people like me believed miscarriages of justice in racially charged cases were impossible. It’s always possible; justice is not decided and delivered by a machine, but by fallible human beings. No, the neuralgic point in the O.J. matter was that so many black people celebrated the verdict as a higher form of justice, knowing full well that O.J. was probably guilty, but rooting for him to beat the system to balance the historical scales.

Marc Lamont Hill is a prominent black public intellectual. He believes O.J. did it, and ought to have been found not guilty. As he explained in a subsequent tweet, the LAPD was caught lying in the trial, and therefore finding O.J. not guilty was the correct verdict. I don’t understand this at all. Even if the LAPD lied, as disgusting as that is, the evidence for O.J.’s guilt was beyond a reasonable doubt, or so it seems to me. The murderer of two innocent people walked free.

The O.J. trial and verdict was a photonegative of To Kill A Mockingbird. Do you remember that novel and movie? Lawyer Atticus Finch demonstrates in court that the black man on trial for raping a white woman could not have committed the crime — but he is convicted anyway, because it was Alabama during the Great Depression, and he was black. The novel is about the loss of innocence of Scout, Atticus’s daughter, who watched it all happen. The O.J. verdict was about a similar loss of innocence, I guess.

What I did not anticipate was that the United States was going to become a country in which the poisonous idea that guilt and innocence, and justice (not only in criminal trials, but socially), can be determined by group racial identity, was going to be institutionalized. That fundamental institutions necessary to running society — law, medicine, academia, and so forth — were going to be transformed according to the same rotten logic that exonerated O.J. Simpson. You might recall my quoting Hannah Arendt’s The Origins Of Totalitarianism, in which she faulted the elites of pre-Nazi Germany and pre-Bolshevik Russia for being willing to knock the pillars out from under their civilizational order, just for the pleasure of seeing those who had been excluded in the past come rushing forward, into the system.

If O.J. were to go on trial today, in 2024, for murder, I have no doubt that very many white people — liberals and progressives of every race, in fact — would be openly on his side from the beginning. No matter what evidence was presented, they would insist on O.J.’s innocence. And see, this too is a sign of a pre-totalitarian society, according to Arendt: one in which people openly decide on right and wrong, depending on how the facts fit into their biases.

Then again, who am I kidding? Only seven years after the O.J. trial, in a very different story, I arranged the facts of the 9/11 attack in such a way that justified my support for war on Iraq. You see, maybe, why I am so stuck on that event, and my reaction to it. It radically undermined what I thought I knew about the power of reason. It’s not a coincidence that at the same time, I kept encountering Catholics who, when confronted about undeniable horrific crimes committed by clergy against children and minors, refused to believe it. They needed to believe that the Church was something that it was not, and no collection of facts was going to shake that confidence. This too wrecked me internally. I really had believed that if you just show people the facts, in a clear and convincing way, they would change their minds, and do the right thing, for the sake of justice.

Nope. And confronting how I twisted myself to justify the violence I wanted America to do to Muslims in the Middle East, as payback for 9/11, showed me that I was just as susceptible as anybody else to believing what I wanted to believe.

The difference is that regarding the Iraq War, I concealed from myself my true motives. In the O.J. Simpson case, many of the black people cheering his acquittal did not do that. Many openly agreed that he was probably guilty. It didn’t matter. Race was everything. Who/whom, as Lenin taught. I posted earlier this week about the Derek Chauvin trial in Minneapolis; Chauvin was the white cop convicted for killing George Floyd. What I had not realized, because I don’t follow news of the case closely, is that there is ample reason to believe Chauvin was railroaded by a system that needed a guilty verdict. The black intellectuals Glenn Loury and John McWhorter get into the issue here. Loury says he was convinced by a documentary film that Chauvin did not receive a fair trial.

Last word: the O.J. Simpson trial was not the first in American history in which a verdict came down based not on the evidence, but on the racial identity of the defendant. But because O.J. was a celebrity, and because the trial took place in an environment of mass media coverage never before possible, it had a cultural impact whose force is impossible to underestimate.

None of us knew it at the time, but the principle illustrated in the O.J. verdict would come to dominate race relations in the United States, to the point where it is harder for people to believe that our system — the legal system, as well as all institutional systems within American society — can be counted on to approximate justice. Racial favoritism, in part under the guise of DEI, corrupts everything. Idealistic liberals used to fight for unbiased justice; idealistic conservatives of the post-Civil Rights era did too, taking comfort in the demonstrated historical truth that if we hold fast to the principles of the American founding, we can purify our society of unjust practices and biases, and get closer to the ideal of equality before the law.

Who believes that now?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rod Dreher's Diary to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.