Randall Sullivan Meets The Devil

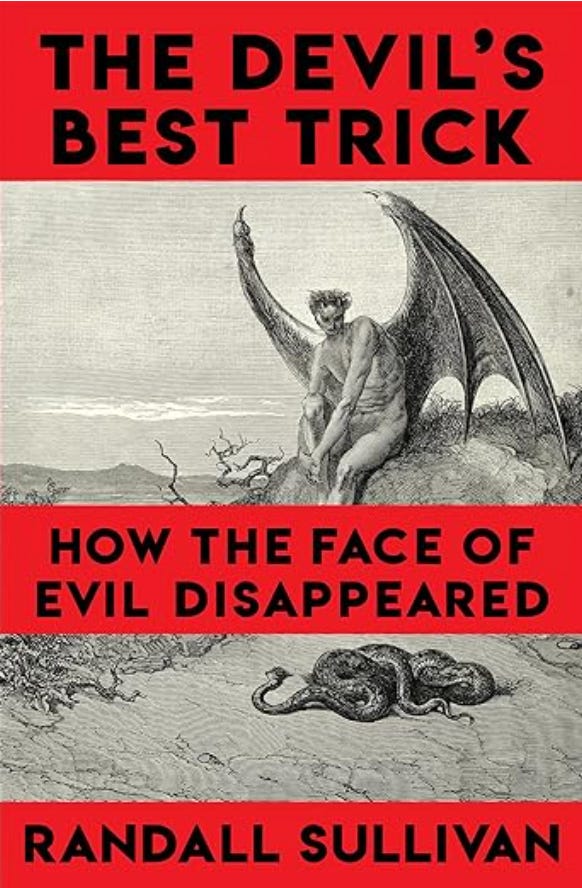

A Review, Sort Of, Of Crime Writer's Terrific New Book 'The Devil's Best Trick'

Hello from Dallas Fort Worth, where I’ve come for the annual Charles Colson conference. Tonight I’ll be interviewed on stage with Kamila Benda. I’ll tell you all tomorrow how this went.

Today I’ve got something very heavy to talk about. Yesterday, after I landed in DFW, the editor of my forthcoming book Living In Wonder texted me this rave NYT review of a new book about the devil:

He added that he thinks Living In Wonder is coming at out just the right time to catch a new popular wave of interest in the numinous. I told him that I once knew Randall Sullivan, a bit. Twenty years ago I had read his book The Miracle Detective, which chiefly focused on the mysteries of Medjugorje, and had been very impressed. Sullivan is mostly a true-crime journalist who wrote for Rolling Stone, and other major publications. Something, can’t remember what now, pulled him towards Medjugorje. Though I didn’t know then and still don’t what to think about Medjugorje, Sullivan’s book about it was a real model of investigative thoroughness and zeal. He came away from it as a Catholic convert, if memory serves — and also told a terrifying story about a mysterious man approaching him on the Piazza Navona in Rome, on his way back home from Bosnia. I was at the time a section editor at the Dallas Morning News, and had invited Sullivan down for a big event we held to talk about his book, and what it had to say not only about religion, but about how we decide what’s real.

I tell you this to say that Sullivan is the real deal. And now he has a book out about the occult — a book over which the Times reviewer raved, saying it scared the heck out of him. (The Washington Post reviewer hated the book, by the way, in part because he considers its point of view to be too Christian.)

Naturally I had to get a Kindle version of the book as soon as I got to my hotel. I read until I could not keep my eyes open any longer, and when I woke up this morning, finished the thing. It’s that kind of book. Let me tell you about it.

The book’s title comes from the well-known saying of the French poet Charles Baudelaire, which goes something like, “The Devil’s best trick is convincing people he doesn’t exist.” The theme of this book could be summed up as: Oh, the devil exists all right, and we in the modern world have set ourselves us foolishly to think he doesn’t — leaving ourselves entirely vulnerable.

The Devil’s Best Trick (henceforth, DBT) is a powerful piece of narrative journalism. Sullivan really knows how to tell a story. My only real complaint about it is that the long passages in which he tracks the historical and theological development of the idea of Satan in Judaism and Christianity slow down the storytelling. I understand why he added this material, but the stories he tells are so riveting that you will be tempted to rush through the theological stuff, and get back to the narrative.

The book focuses on two basic stories through which Sullivan examines what he considers to be the manifestation of Satanic evil: the culture of brujeria (black magic sorcery) in Mexico, and the long-unsolved death of a teenage boy in small-town Texas that almost certainly involved a satanic cult. There are three minor themes: a) how most of the leaders of the late 19c Decadent movement had been involved with the occult, but reconciled with the faith before death; b) the story of one of North America’s worst sex killers, and his redemption before his execution; and c) a true account of a spectacular, well-documented 1928 exorcism in the US.

Early in the book, preparing to go to the Veracruz town that’s the center of brujeria, Sullivan consults the leading US academic expert on Mexican occultism:

I repeated what I had heard from Antonio Zavaleta, a professor of anthropology in the University of Texas system and the closest thing to an authority on the subject of Mexican witchcraft as exists in American academia. Zavaleta, half Mexican and half Irish, told me that he had struggled for decades with what for him was still an unresolved dichotomy: “In the Mexican culture, things that would be seen by you and me as clearly defined evil aren’t seen that way at all. For instance, the use of a supernatural medium to accomplish someone’s death would clearly be considered evil by American standards. But here at the border [Zavaleta was living in Brownsville, Texas] it is part of everyday life. People don’t see it as evil, or in terms of right or wrong. They don’t understand it in those terms. It’s just part of their cultural reality. If you’re able to manipulate the spiritual or supernatural world, then you have a right to. This is a power you possess and you can use it if you want.”

For me, this is one of the most important points the book makes. Over and over, I kept thinking about how we in the modern West — even many Christians — have buffered ourselves from the darkness in the rest of the world. Or, more neutrally, we have locked ourselves up in a rationalist citadel that prevents us from understanding what the real world is like. We tell ourselves it’s not real, that it’s “superstition”. Our ancestors knew better. Peoples of the so-called Third World do too.

As priests who live among and work with Latin American communities have told me over the years, one of the biggest struggles they have is convincing even faithful Catholics to stay away from this stuff. One priest who serves a US-Mexican border community told me once that he routinely goes to clean out demonic activity in the houses of parishioners. He admonishes them to stop going to the curandera, stop shopping at the botanica, and so forth. That’s how you invite this stuff into your lives and your homes, even if you think it’s just “white magic”! But most of them never listen.

What sent Sullivan to Catamaco, the Veracruz town? An interview he had done with Ron Willhite, a prison chaplain who had been part of the pedophile serial killer Westley Allan Dodd’s prison conversion. Sullivan writes about what Dodd did, telling us that he’s sparing us most of the details, because they are too horrible to contemplate (I believe him). And yet, in prison, prior to his execution, Dodd became a Christian — even as he insisted that he deserved to die for what he had done, and also to protect society from himself. Willhite, who was himself a hellraiser until his own conversion, chokes up as he talks about how Dodd, over the course of his repentance, confessed all of his sins, and made himself clean.

[Willhite] was unable to speak for several minutes, managing only deep breaths and barely suppressed sobs. When he finally squeezed out half a word, he choked up again, gasping for breath. Finally, between deep sighing breaths, Willhite got out the words, “I can tell you that Westley Allan Dodd that night left the earth as clean as any man has ever left this earth. He didn’t lie to himself or to me or to God about one tiny thing.”

Dodd’s final statement before his hanging was to testify to the power of Jesus Christ to save souls. Sullivan:

My conversation with Ron Willhite troubled me almost as much as the anonymous letter. I was unable to accept what he’d told me about Westley Allan Dodd “coming clean,” but I couldn’t bring myself to reject it, either. Stymied, I had no idea what to do next or who to seek out. Then, right after I decided to put this book aside, it struck me that what I needed to continue might be found in a part of the world where people accepted the reality of good and evil unimpeded by any fog of modernity that obscured the meanings of the words. Some place where God’s existence was a given and where the Devil was not a symbol or a concept, but an actual being from whom one might either flee or seek favors. I had heard of such a place.

So, Sullivan and his translator Michelle Gomez head off to Catemaco, for the annual witches gathering in early March. It’s a time when most of Mexico’s sorcerers and witches gather for black masses, ritual sacrifices, and open Satan-worship. It has become commercialized now, but back when it started there, in the 1970s, there were two very powerful sorcerers — Gonzalo Aguirre and his teacher, Manuel Utrera, who was so feared that fifty years after his death, local people don’t want to speak his name.

Sullivan takes a long historical detour to the days of the conquistadors and what they found when they arrived in Mexico: an Aztec empire in which the mass human sacrifices beggared belief. I had not realized how fully attested to this stuff is by the historical record. As Sullivan avers, in contemporary times, we have scrubbed our awareness of this stuff, in service of an agenda that paints the Spanish as evil exploiter of innocent native cultures. You don’t have to think of the Spanish as saints and angels — they weren’t — to understand that they confronted evil so raw that it beggars imagination.

Here is a characteristic passage:

The Spaniards’ new residence was directly across from the spectacular pyramidal temple of the Hummingbird Wizard. The temple had been dedicated just thirty-two years earlier by the man regarded as the architect of the Aztec Empire, Tlacaelel. The highlight of the ceremony was the greatest human slaughter in the history of the Mexica—eighty thousand sacrificed, according to a sixteenth-century Aztec historian; the lines of those who would die stretched for miles, he recalled, and the killing went on without interruption for four days and nights. The Aztec nobility were provided with seats in boxes covered with rose blossoms intended to mask the smell of drying blood and rotting flesh. The stench was overwhelming, though, before even a thousand were dead, and by the second day nearly every one of the boxes was empty.

Yet the eighty-nine-year-old Tlacaelel remained the entire time, personally observing each and every sacrifice. It was Tlacaelel who had instituted Aztec worship of Huitzilopchtli, the Spaniards would learn, and who had invented the “Flower Wars”—contrived conflicts with neighboring tribes that were intended only to take prisoners for sacrifice to the Lover of Hearts and Drinker of Blood.

It is very, very, very bad. Words fail. If you saw Mel Gibson’s Apocalypto, you know what happened there. It’s all based on contemporary historical accounts of both Spaniards and Aztecs — accounts that have been backed up by archaeological discoveries. Though many of the conquistadors did become exploiters, there can be no doubt that Cortes came up against a kind of evil that would not be seen again until the 20th century, with the Holocaust. True, this doesn’t exonerate the conquistadores of whatever evils they may have done, but then, whatever those evils may have been, they absolutely pale by comparison to the unfathomable evils from which the Spanish delivered the peoples of Mexico. We shouldn’t be embarrassed to say so. Sullivan:

For Christians, Catholics in particular, it was for hundreds of years an article of faith that what Cortés and his men confronted at Tenochtitlan had been the Devil’s own empire. As the Catholic writer Warren H. Carroll observed of fifteenth-century Mexico, “Nowhere else in human history has Satan so formalized and institutionalized his worship with so many of his own actual rites and symbols.”

Sullivan makes a good case, I think, that we moderns prefer to downplay or deny this raw evil because it suits our political ideology, or perhaps we are too afraid to confront it. I remember in 1989, reading the stories of the abduction and murder of Mark Kilroy, a US college student on spring break in Matamoros, Mexico. He was taken by a cult, sodomized, tortured, and ritually murdered, with his body parts cooked in a cauldron. At least fourteen others had died the same way. The cult leader said that this would give its members protection against the police in their drug smuggling. I read those stories that spring, my last one in college, and marveled not only that such things happened in the world, but that it had happened literally just across the US border.

It’s too much to take in, so we either find reasons to explain it away, or we just don’t think about it. This is perhaps Sullivan’s main point in the book: that if supernatural evil exists, then the world is very different than what we would prefer it to be. Sullivan reports at the end that he came to believe in the Devil at the end of his investigations, and got to the point where he read events in the world as physical manifestations of a deeper spiritual war. In Living In Wonder, a Catholic man tells me that dealing with his wife’s possession and deliverance changed him in that now, when he walks down the streets of Manhattan, he realizes that all around him, hidden from his eyes, is a vast spiritual clash.

Sullivan reflects here on what fools we are to think that evil is merely a matter of corrupt systems, or a deficiency of love. Westley Allan Dodd was loved by his parents (he said), and he went to his own execution feeling remorse for how he paid back that love by doing evil. Yet he had had these evil urges to rape and murder children since a young age. Even after becoming a Christian, he recognized that there was something deep inside him that was not removed by his conversion — and that’s one of the reasons he needed to die.

Sullivan, on the insufferable naivete of our criminal justice system:

In Dodd’s case, the passes he received from the criminal justice system seemed to even more clearly echo what Jeffrey Burton Russell had said to me about the inability of educated people in the contemporary world to comprehend that there actually was such a thing as evil. In 1981, while enlisted in the navy, Dodd had gotten off with a warning after attempting to abduct a pair of little girls. Less than a year later, while still in the navy, Dodd was taken into police custody after offering a group of boys $50 each to go with him to a motel to play strip poker. Yet even after he admitted that he intended to molest the boys, the charges were dropped because the parents didn’t want to put their sons through the ordeal of a public trial. Just months later, Dodd’s approach to a young boy in a public restroom resulted in his conviction for “attempted indecent liberties” and a jail sentence of nineteen days. The navy gave him a general discharge and sent Dodd on his way. Within the year, he was arrested for molesting a ten-year-old boy, but somehow drew a judge who gave him a suspended one-year sentence, on the condition that he receive counseling.

The Dodd case is almost uniquely horrible, but we see the same kind of naivete in the discussions, especially among elites, about how bad the “carceral state” is, and how awful the police are, and so forth. Evil is rarely simple, but these people complexify it away. They’re doing this, Sullivan’s narrative suggests, because they cannot bear to face what evil truly is.

Sullivan discusses the cult of Santa Muerte (Saint Death) in Mexico — how it first became celebrated among cartel members, and now is far more widespread:

The Catholic Church had imagined [popular devotion to Santa Muerte] might change when David Romo was arrested in December 2010 on charges that he had been doing the banking for a kidnapping gang linked to a drug cartel. Yet even when Romo was sentenced in 2012 to sixty-six years in prison after being convicted of crimes that now included active participation in kidnapping, robbery, and extortion, the Church of Santa Muerte continued to thrive. In part this had to do with the fact that the cartels were running what were arguably the most profitable businesses in Mexico. It certainly didn’t hurt, though, that Santa Muerte devotion was increasingly identified not just with criminal enterprises but also with societal outcasts in general. Large swaths of the homosexual, bisexual, and transgender communities had adopted Santa Muerte as their “protectress,” and soon the Church of Saint Death was the only significant organization in Mexico that recognized gay marriage and performed wedding ceremonies for homosexual couples.

When you asked Mexican people about their devotion to Santa Muerte, though, they almost always answered that they worshipped her because she was so much more generous about dispensing favors than the saints of the Roman Catholic Church. “Prayers to Santa Muerte get results,” a woman operating a stall on the zócalo in Veracruz told me.

An exorcist in Rome told me that one appeal of the occult is that when you call them, demons will come. They will do your bidding. But there is a price to be paid. Young people especially are drawn into these practices by the mystery, and because this stuff really “works,” in that they get things, or see things. Sometimes, they are tricked into believing that Satan isn’t real, that he’s only a symbol. A friend of mine, now Christian, who was once a Satanist recently warned a young man active in Satanism, who told my friend that he doesn’t believe Satan truly exists, “That’s what they tell you at first, but the deeper you go into it, you learn that he really does.”

I found the Mexico parts of Sullivan’s book the most compelling, for two reasons.

First, it reveals how deeply occultism is woven into the mentality of Mexicans, with celebrities, politicians, and wealthy Mexican oligarchs openly consulting with brujos to achieve fame, fortune, and power. (In other words, it’s not just the cartels.) In one scene, when Sullivan and his party go up to the Devil’s Cave, a place where the chief brujos perform sacrifices, they are interrupted by a small group of federales, policemen who are there to keep the piece at the witch festival, some of whom want to go into the cave to ask the demons purported to live there for favors on this most propitious day of the year. This stuff is real:

[The academic Antonio Zavaleta] had seen any number of visitors from places like New York and Los Angeles suffer terribly for their failure to appreciate the danger that brujería represented.

Zavaleta told me. “I worked on this National Geographic piece on Mexican witchcraft,” he said, “and I know that many of the people who worked with National Geographic on that got very sick and are still sick. This is serious stuff. You start trying to break the curse a brujo has put on someone, that power can turn on you. It’s dangerous work.”

The second reason I found the Mexico part of the book its strongest is the discussion of how these evil spirits were conquered by the Spaniards — and by Christ, in part through Our Lady of Guadalupe — but they never really went away. They were only submerged. And now they are reasserting themselves. Later in the book, going over the well-documented accounts of the 1928 US exorcism, Sullivan is started to read:

According to both priests, when [Father] Steiger demanded to know how this demon (or the Devil, if [Father] Riesinger was correct) imagined he might challenge the power of Jesus Christ, the answer was, “Do you know the history of Mexico? We have prepared a nice mess for Him there.… He will learn to know us better.”

What we see openly in Mexico is something we see in a more veiled way here in the US. But it is here. The other big narrative in the book is the failed attempt to solve the apparent suicide of teenager Tate Rowland, in the Texas Panhandle town of Childress. The extensive true-crime reporting Sullivan does here makes it as clear as clear can be that there was an occult dimension to the crime. But this has been impossible to prove, Partly, the book suggests, because there’s a reason this stuff is called “occult,” which means “hidden”. It is also partly because this stuff is so far out that investigators often lack the expertise to understand what they’re dealing with. And it’s partly because we just don’t want to face up to the possibility that this is real; the overreaction of the “satanic panic” of the 1980s serves to discredit any occult claims.

The Mexican narrative is far more compelling, but who knows? The fact that a murderous Satanic cult almost certainly operated in a small Texas town in the middle of nowhere for a time, and even killed a popular kid — and got away with it — might be more unsettling to American readers, who cannot finish this book thinking that the occult is something that happens across the border, but not among us. As an exorcist tells me in Living In Wonder, there is no such thing as a spiritual vacuum. When the religion of Christ withdraws from the infidelity of the people, the dark side advances. If we tell ourselves we can live in neutral territory, it’s a lie.

I also appreciate how Sullivan compels us to recognize how we moderns lie to ourselves about what it really means to live in a world without God. He discusses how philosophers and theologians, in modern times, diminished and even dismissed the Devil as a real entity. He might have discussed how Nietzsche was one of the first atheist philosopher to truly see that a godless world is not the happy-clappy paradise that the philosophes dreamed of, but a world where will to power is everything. Instead, he discussed how it was the demonic Marquis de Sade, a contemporary of the French philosophes, who revealed the true dark side of their hatred of Christianity:

In an intrinsically valueless world, Sade contended, the only sensible course was the pursuit of pleasure: If you enjoy torture, well and good. If others do not enjoy torture, they need not engage in it, but they have no business imposing their own tastes upon you. Violations of the so-called moral laws are not only permissible but actually commendable, because they demonstrate the artificiality of such restraints, restraints that serve only to obstruct the exalted striving toward the satisfaction of one’s appetites.

Sade’s philosophy could be boiled down to a single sentence, Russell had written in Mephistopheles: “The greater the pleasure, the greater the value of the act.” Sexual pleasures should be pursued with absolute abandon, Sade had insisted, and since crime could provide an even more intense experience, the greatest satisfaction one could obtain was to combine sex and crime. For Sade, “the greatest pleasure comes from torture, especially of children,” Russell explained. “If one humiliates and degrades the victim, the delight is further enhanced. Cannibalism, for some, may add to the intensity of the experience. And the purest joy, exceeding even sexual pleasure, is to commit crime purely for its own sake in a gratuitous act of what the ignorant call evil.”

I found myself simultaneously smiling and shaking my head as Russell seemed to extol Sade for the courage of his convictions. The professor paraphrased what he had written in Mephistopheles: “Sade forces us to face the dilemma. Either there are grounds of ultimate concern, grounds of being by which to judge actions, or not. Either the cosmos has meaning, or not. If not, Sade’s arguments are right. Sade is the legitimate outcome of true atheism, by which I mean a denial of any ground of ultimate being.”

As T.S. Eliot might have said: “If you will not have God — and He is a jealous God — then you should pay your respects to the Marquis de Sade.”

That’s the big takeaway of The Devil’s Best Trick: There is no middle ground. There is a spiritual war going on, one that has been happening since the beginning of time, and that you must choose sides. There are a thousand and one reasons why we talk ourselves out of facing the realities of spiritual evil, but it remains there — and you cannot compromise with it. I don’t know about you, but I find my faith strengthened by reading books like this; they remind me of the stakes.

This book has also reminded me of the cost of living by lies, in a way I hadn’t thought of before. If we pull our punches in talking about the evil of crime, or the evil of sexual perversion, the evil of occultism in all its forms, the evil of transgenderism, or any of the other evils that present themselves to us today as either goods, or as something whose nature is other than it is — we are fools. I’m talking in part about the evils we normalize in gangsta rap and popular music (including things like NPR folks chirpily praising the filthy “W.A.P.” as liberating) and the various manifestations of porn culture, but mostly here I’m talking about liberals and others who think that crime can be entirely explained by materialist means, and who are tempted to go easy on people like Westley Allan Dodd.

The public rhetoric we had about the evils of the “carceral state” around 2020 and thereafter were a distraction from the fact that some people are so evil they must be put away from society. Reading this book, I thought about Nayib Bukele, the president of El Salvador, who has violated many canons of liberal democratic thought to jail mass numbers of drug gang members. MS-13 is the major gang there — and, as this Washington Post report details, many of whom are open Satan worshipers.

Bukele, who praises God in his public rhetoric, has a far better understanding of how to deal with evil than his liberal North American critics. No wonder he’s so popular among Salvadorans. He has brought them peace.

One last note about Sullivan’s excellent book: he talks about going to see the aged daughter of Gonzalo Aguirre, who was the most famous sorcerer in Mexico until his death. He openly spoke of his dealings with the Devil. His daughter Isabel claimed to be a white witch only, and told a story about how her father refused to let her study black magic. One day he asked the Devil to show her that he was real, and he did. Sullivan says he saw a photo of Aguirre in the house, and was deeply struck by the sense of utter desolation and hopelessness in the man’s face, as if he had seen and done things for which there is no redemption.

There’s no photo in the manuscript, but I found this one of Aguirre online:

I see what Sullivan means. Look at those eyes. That is a man who literally sold his soul to the Devil. We learn that he attempted at the end of his life to revoke the bargain. Whether he succeeded, we can’t know.

I hope you will buy Randall Sullivan’s new book. It’s impossible to put down. It’s not only scary, but raises profound and urgent questions about what it means to live in the world as it truly is, not as smug, know-it-all modern Westerners would like it to be.

Last week, I was talking to someone who asked what my next book is about. I told them. The person said, “Aren’t you afraid that people will think you’re crazy?” I responded that I am certain more than a few people will, but at this point in my life, I don’t care. I’ve got to tell the truth as I see it. I believe in God. I believe in Jesus Christ. I believe that the Devil is real. And I believe that the world is not what most of us in the modern West think it is. I don’t just believe that; I know that.

Living In Wonder Note

Say, readers, for you who want to pre-order my book, I have been linking to the Amazon site for pre-orders, but Warren Farha of Eighth Day Books in Wichita is setting up an online pre-order page for the book, which will be released nationwide on October 22. If you want a signed copy of the first edition, order it from Eighth Day, which will be the exclusive source for signed copies. I’ll post an Eighth Day link when it’s up. Meanwhile, I know some of you don’t like buying from Amazon, so I’m going to ask Zondervan if there’s a page we can create with purchase links from Barnes & Noble and other major retailers.

A bit of advice for everyone: do NOT read and/or collect lots of books about evil and possession. Read just enough to open you eyes then stop. Thats enough to change your life for the better. If you go further, Evil takes notice of your "interests."

I can personally attest to the very real existence of the Devil. The Devil is not an abstraction or a symbol, but an—entity, perhaps?—that actively, maliciously, and deliberately desires the enslavement and ultimately the death of each human being. And the Devil will convince you that that is what you want for yourself as well.

Take heed!

One favor the Devil did for me: he overplayed his hand and revealed himself too clearly. And the revelation of the existence of the Devil necessarily implied the existence of God. I'm not at all sure that I ever would have come to any sort of faith at all had I not seen the face of evil so clearly.

And how do I know that? I've seen that look in Gonzalo Aguirre's face in my own eyes. May those days be forever behind me!