Rocamadour: A Christian Israel

The Meaning For Our Time Of The Medieval French Pilgrimage Destination

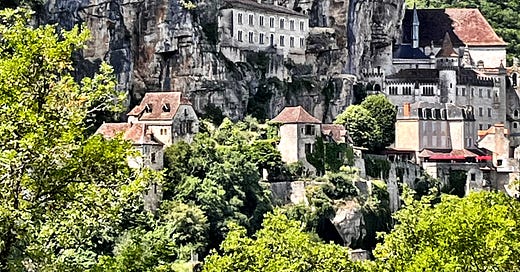

That, my dears, is the medieval cliff village of Rocamadour, deep in the countryside of southwestern France.

It is a famed pilgrimage site, and was on the historic route to Santiago de Compostela. Today it contains a small village at the base of the cliff, chapels and religious buildings halfway up, and a fort built on top to protect the religious sites. Though there is evidence that Christian worship happened there in early medieval times (and pagan worship before that), the complex began in the early 12th century by the building of a small chapel in the side of the rocky cliff. A wooden carving of the Virgin and Child was discovered there, and is now revered as the Black Madonna. The statue is today displayed clad in a robe, but here is what she looks like uncovered:

It was widely believed in the Middle Ages that the image was wonderworking; many miracles have been associated with it. In 1166, hile digging a grave near the entrance to the chapel of the Black Madonna, monks discovered in a cave the incorrupt body of St. Amadour, which legend held was actually Zacchaeus from the Bible, but there is no evidence of that.

St. Amadour’s body was displayed in the church, but was destroyed by Protestants during the French Wars of Religion, when they sacked the complex. The French Revolutionaries had a go at it too. All that remains of the saint is a bone, on display in the basilica attached to the chapel:

I first became aware of this place a decade ago, reading Houellebecq’s novel Submission. The protagonist, a dissolute Sorbonne professor named François, faces a life choice as Islamists democratically come to power in France. If he converts formally to Islam (they don’t care if he really believes), he gets a promotion and three wives. As he is thinking it over, François makes a sudden pilgrimage there, as a diversion from a holiday in the country. The idea of going to Rocamadour is suggested to François by someone he meets on the vacation:

“You must go, truly you must. It’s just twenty kilometers away, and it’s one of the most famous shrines in the Christian world. Henry Plantagenet, St. Dominique, Saint Bernard, Saint Louis XI, Philip the Fair — they all knelt at the foot of theBlack Virgin, they all climbed the steps to her sanctuary on their knees, humbly praying that their sine be forgiven. At Rocamadour you’ll see what a great civilization medieval Christendom really was.”

So François goes there, and finds the small, dark chapel of the Black Madonna very moving. Here is what he sees there, what I saw there, high over the altar:

On his last day in Rocamadour, François sits in the back of the nearly-empty chapel. “Most of the audience was made up of young people in jeans and polo shirts, all with those open, friendly faces that for whatever reason you see on young Catholics,” François says. There, François hears someone reading verses from the twentieth-century French poet and Catholic pilgrim Charles Péguy, addressed to the Virgin:

Mother, behold your sons who fought so long.

Weigh them not as one weighs a spirit,

But judge them as you would judge an outcast

Who steals his way home along forgotten paths.

François, who is so very, very lost:

The [verses] rang out rhythmically in the stillness, and I wondered what the patriotic, violent-souled Péguy could mean to these young Catholic humanitarians. In any case, the actor had excellent diction. I thought that he must be a well-known theater actor, a member of the Comédie Française, but that he must also have been in the movies, because I’d seen his photo somewhere before.

Mother, behold your sons and their numberless ranks.

Judge them not by their misery alone.

May God place beside them a handful of earth

So lost to them, and that they loved so much.

He was a Polish actor, I was sure of it now, but still I couldn’t think of his name. Maybe he was Catholic, too. Some actors are. Its true that they practice a strange profession, in which the idea of divine intervention seems more plausible than in some other lines of work. As for these young Catholics, did they love their homeland? Were they ready to give up everything for their country? I felt ready to give up everything, not really for my country, but in general. I was in a strange state. It seemed the Virgin was rising from her pedestal and growing in the air. The baby Jesus seemed ready to detach himself from her, and it seemed to me that all he had to do was raise his right hand and the pagans and idolators would be destroyed, and the keys to the world restored to him, “as its lord, its possessor, and its master.”

Mother, behold your sons so lost to themselves

Judge them not on a base intrigue

But welcome them back like the Prodigal Son.

Let them return to outstretched arms.

Or maybe I was just hungry. I’d forgotten to eat the day before, and possibly what I should do was go back to my hotel and sit down to a few duck’s legs instead of falling down between the pews in an attack of mystical hypoglycemia. I thought again of Huysmans, of the sufferings and doubts of his conversion, and of his desperate desire to be part of a religion.

I stayed until the reading ended, but once it was over I realized that, despite the great beauty of the text, I’d have preferred to spend my last visit alone. What this severe statue expressed was not attachment to a homeland, to a country; not some celebration of the soldier’s manly courage; not even a child’s desire for his mother. It was something mysterious, priestly, and royal that surpassed Péguy’s understanding, to say nothing of Huysmans’s. The next morning, after I filled up my car and paid at the hotel, I went back to the Chapel of Our Lady, which now was deserted. The Virgin waited in the shadows, calm and timeless. She had sovereignty, she had power, but little by little I felt myself losing touch, I felt her moving away from me in space and across the centuries while I sat there in my pew, shriveled and puny. After half an hour, I got up, fully deserted by the Spirit, reduced to my damaged, perishable body, and I sadly descended the stairs that led to the parking lot.

François returns to Paris, makes his Islamic profession of faith, and is set for life. Again, he doesn’t believe in Islam at all; it is a cynical conversion for the sake of worldly gain. I think even a believing Muslim would say this is spiritual death.

This is a powerful passage from a prophetic novel. Submission is not really about Muslims, but about the French as a spiritually and morally exhausted people. They choose to submit to Islamic rule because they don’t know what else to do, and the Islamists — “soft” Islamists, like Erdogan of Turkey, not the hardliners of ISIS — at least believe in something. Maybe, like the barbarians of the Cavafy poem, “are a kind of solution” to the problems of decadence and nihilism.

What we see in this passage — which is the book’s climax — is a contemporary French intellectual who tries to reconnect with his nation’s glorious past, which is rooted in Christianity. He is absolutely a prodigal son who has wasted his intellectual gifts, and has reached middle age as a lonely drunk. In one sad passage, his younger girlfriend, a Jew, flees the coming Islamist government for Israel. François laments that Gentiles like him have no Israel into which they might seek refuge.

But in my view, Rocamadour, and what it symbolizes, is a kind of Israel for Christians. It really is true that you can sense the greatness of medieval civilization at Rocamadour — a greatness that was built on the Christian faith. François sits in the tenebrous chapel feeling the weight of his prodigality, and wanting to believe. Then, crucially, he has a mystical experience — but brushes the invitation to faith aside, guessing that it must be a hallucination from having not eaten.

Notice that François experiences the Virgin, in that setting, as symbolizing more than a call to personal conversion. She stands for something deeper and broader: for the rebirth of a once-great civilization based on the worship of her Son, and all that entailed. I don’t think it’s too much, given the context of the narrative, to say that Houellebecq identifies the only way to save France is by a return to the intensity and conviction of medieval Christianity. After all, Muslims also built a great civilization on the basis of their religion.

Houellebecq has said elsewhere that he is a follower of Auguste Comte, the 18th century philosopher who founded the discipline of sociology. Comte was a secularist, but he recognized as an anthropological and sociological fact that any civilization required a religious basis. And not just “cultural” religion, but real religion. According to Louis Betty, in his must-read book about Houellebecq as a prophetic novelist of post-Christian Europe:

The unbinding of humanity from God lies at the heart of the historical narrative the reader encounters in Houellebecq’s work: lacking a set of moral principles legitimated by a higher power and unable to find meaningful answers to existential questions, human beings descend into selfishness and narcissism and can only stymie their mortal terror by recourse to the carnal distractions of sexuality. Modern capitalism is the mode of social organization best suited to, and best suited to maintain, such a worldview. Materialism — that is, the limiting of all that is real to the physical, which rules out the existence of God, soul, and spirit and with them any transcendent meaning to human life — thus produces and environment in which consumption becomes the norm. such is the historical narrative that Houellebecq’s fiction enacts, with modern economic liberalism emerging as the last, devastating consequence of humanity’s despiritualization.

“Materialist horror” is the term most appropriate to describe this worldview, for what readers discover throughout Houellebecq’s fiction are societies and persons in which the terminal social and psychological consequences of materialism are being played out. It is little wonder, then, that these texts are so often apocalyptic in tone.

Here is a vital quote from Betty’s book — vital, that is, to understanding The Benedict Option:

Houellebecq’s novels suggest that once religion becomes definable as religion — that is, once its symbols no longer address themselves to society at large as representative of discipline and moral authority, but rather address only the individual as motivators of religious “moods and motivations” — it is already doomed. Religion must do more than provide a space for the individual to enter, à la [anthropologist Clifford] Geertz, into the “religious perspective.” This is simply not enough for modern people; the symbols therein are too weak, too uncoupled from ordinary existence to give serious motivation. Religion must set a disciplinary canopy over the head of humankind, must order its acts and its moral commitments, must furnish ultimate explanations capable of determining the remainder of social life; otherwise, religion loses itself in the morass of competing perspectives (scientific, commonsense, political, etc.) This is precisely what has happened in the West… .

In the case of Christianity in Europe, I think the question to ask is something like this: can a civilization maintain its identity if it sheds its native religion? Houellebecq doesn’t think so, and neither do I. This isn’t a political or polemical point. Imagine taking as an anthropological platitude the claim that human beings will be religious and, moreover, that civilizations are built upon the metaphysical systems they create (or which are revealed to them, to give credit to the metaphysical on its own terms). It’s obvious from such an assumption that the collapse of the metaphysics entails the eventual collapse of everything else. This should be deeply alarming to anyone who cares about the West’s tradition of humanitarianism, which emerges—and it would be wonderful if we could all agree on this—out of the original Judaic notion of imago Dei and later from Christian humanism. Secular humanism has been running for quite some time on the fumes of the Judeo-Christian religious inheritance, but it’s not clear how much longer that can go on.

Honestly, it’s frightening to think what a truly post-Christian West would mean for our basic institutions. I’m not stumping for Christianity here; I just happen to have the intellectual conviction that the analysis of human society begins with religion. If you incline toward Marxian thinking, which looks at things in the diametrically opposed way, you’re going to hate what I’m saying. But that’s how I see it.

Later in the interview, Betty says that

… a purely economic understanding of the human being, in which we are reduced to consumers and consumed, can only follow upon a deeper ontological shift from a theological (and, in the case of Houellebecq, Christian) worldview to a materialist one. If there is no soul, no inviolate and irreducible part of our identity that both escapes all material and social determination and is of equal value regardless of circumstance, the door is opened, at least in argument form, to whatever dehumanizing forces one cares to imagine.

More concretely, you don’t get white supremacy if you believe that every human being has a soul fashioned in God’s image. Neither do you get far-left racial and ethnic identitarianism. Both are symptoms of a metaphysical deficit. It’s very easy to start dividing people up into tribal categories; after all, humans vary massively in just about every imaginable quality. It’s really something of a miracle that we ever came up with a notion of common humanity at all! We have the Judeo-Christian heritage to thank for this in the West. This is something secular people ought to consider before making glib criticisms of traditional religion.

Yes. The words of one of the young pilgrims I met on the Chartres pilgrimage have been much on my mind these past few days. He said that he discovered traditional Catholicism during Covid, when he had a lot of time to spend online. As you know from my recent writing, a number of young men just like him — disconnected from any serious Christianity — discovered tribalism and white supremacy. It is sadly true that there are white supremacists who claim the mantle of Christianity, but theirs is a false Christianity.

The point is that this decadent, deracinated, materialistic society and culture into which young people have been thrown by history and the lassitude of their parents’ generation cannot sustain itself. It will require something more — something that binds. (Betty: “Religion must do more than provide a space for the individual to enter, à la [anthropologist Clifford] Geertz, into the “religious perspective.” This is simply not enough for modern people… .”) To borrow from Eliot, if we will not have God — the strong God of medieval Christianity — then we had better be prepared to pay our respects to Allah, or to the sacralized Tribe (race), or some totalitarian ideology as yet to emerge.

In the Houellebecq passage from Submission, we see François recognizing that it is not enough to see Mary as a portal through which one goes seeking personal salvation in Christ, and comfort, and release from one’s own suffering. If the civilization that was once Christendom is to survive, it will have to reconnect with God in a much more profound and encompassing way. It will have to reconnect with God the way the medievals did. This was beyond François’s ability, because he lacked the courage to follow through on the mystical revelation he received in the dark chapel of Rocamadour.

I think I understood what Houellebecq’s character meant by going to Rocamadour shows you what a powerful civilization Christendom was in the medieval age. Yes, there are signs of national and martial glory (there is a medieval sword jammed in a rock over the chapel; the unbelievable legend has it that it was a sword thrown by Roland, in the Chanson de Roland, that flew hundreds of miles away to lodge in the rock. The guide pamphlet I had said drily that centuries ago, a pilgrimage site had need of those kinds of relics.) But Rocamadour is not primarily about personal salvation or national pride or civilizational greatness, though those elements are there. It is above all about the profound encounter with the mystery of God, the God who created the cosmos, and infuses it with His power, and summons us to His service.

As you will recall, I had my own mystical encounter in the Chartres cathedral, aged 17. For years I tried very hard to make Christ part of my life. It was futile. Christ did not seek admirers; he wanted disciples. Either He is the Lord, or He is not. Once I finally understood that, and submitted to Him, my faith became real. Not easy — as God and my confessor well know! — but real.

As I write in Living In Wonder:

In the seventh century, Maximus the Confessor made perhaps the most profound case of all for how we can recognize God in creation. The theologian explained that humans participate in the life of God through the logoi—the essential reasons for being—embedded within ourselves and all created things. The logoi within creation are in a real sense the incarnation of God’s ideas. Our divinely ordained task as humans is to elevate all things to deeper participation in the Logos. This is what Father Chrysostom, the Romanian monk, meant when he told me that contemplating beauty draws us out of ourselves and toward God, for the Logos, Jesus Christ, calls out to all logoi to show themselves and join to him.

The work of the priest—and all human beings play a God-ordained priestly role in this sense—is like the work of an artist: to refine creation, revealing its logoi more purely and reuniting them to the Logos himself. As the man of faith does with his own soul, constantly moving it toward theosis, so, too, he does this with the material world—using his creativity to draw the meaning out of creation and perfect it in an offering to the Creator.

It sounds pretty abstract, admittedly, but, in truth, it could hardly be more concrete. Saint Athanasius, the fourth-century bishop and church father, taught that, once upon a time, men had lost sight of God’s presence in the world, believing that the material world was all that is. God needed to remind them that he, the Lord their God, is everywhere present and fills all things. As Athanasius writes in his classic work On the Incarnation, “The self-revealing of the Word is in every dimension—above, in creation; below, in the Incarnation; in the depth, in Hades; in the breadth, throughout the world. All things have been filled with the knowledge of God.”

God’s choosing to take on flesh and blood and enter into time to be with us mortals revealed the inherent sanctity of all creation. This is why contemplating created things—stars, mountains, paintings, violin quartets, or the intricate form of a child’s ear—is in a real sense to contemplate God through the visible or audible signs of his handiwork.

This is how Christians of the Middle Ages saw the cosmos. Umberto Eco said that it’s not the case that medievals looked at the world and said, “Ah ha, that apple tree reminds me of God.” Though they may not have read Saint Athanasius or had any theological knowledge beyond the basics, people back then naturally saw no strong divide between Creator and creation. For our ancestors in the faith, said Eco, the entire world was “an immense theophanic harmony. . . . The face of eternity shines through the things of earth, and we may therefore regard them as a species of metaphor.”

Unless we Christians today learn to once again see all the world as metaphors in a cosmic book authored by God, we may never know enchantment. At the conclusion of Dante’s journey into Paradise to see the face of God, with his vision purified, the poet says of beholding the eternal Light into the profoundest nature of things:

In its profundity I saw—ingathered

and bound by love into one single volume—

what, in the universe, seems separate, scattered . . .

—Paradiso 33:85–87

Do you get it? You don’t go to Rocamadour to be reminded of God, and the things of God. If you go there as its original pilgrims did, you go there to meet God, through the media of the Sacraments, through the miraculous statue, through the steep stone staircase that the most devout of ages past climbed on their knees. The physical ardor was a sign of how deeply the pilgrim received the encounter; as the anthropologist Paul Connerton said, the kind of faith that endures the currents of liquid modernity is the sort that involves the body in worship, for that sediments the teachings into one’s bones. Motoring through the hills and forests surrounding Rocamadour, it struck me how much faith the medieval pilgrims who passed through here on foot, on their way to Santiago de Compostela, must have had — that is, how overwhelmingly their religious belief was their reality. Not a part of reality, but reality itself.

I don’t know if we can get this back. We can’t un-know what we have come to know in the centuries since the end of the Middle Ages. But Rocamadour is still there. The Holy Virgin is still calling those with ears to hear. This morning, back at the Monastery of Sainte-Marie de la Garde, listening to the Benedictines chanting their morning prayers in Latin, à la gregorien, there it was, a living presence. Quoting Benedict XVI, the abbot told me before I departed with my friend that the faith attracts people; it doesn’t impose itself on them. This, he said, is why more and more, the monks find people from all over France are buying second homes in the vicinity of the abbey. They know that there is power there, and rest, and serenity — and they want to draw close to it.

Christian kings and clerics did impose the faith in the past, but that cannot be the case anymore. Yet to go to Rocamadour, to go to Chartres, to spend time in that humble abbey in the rolling hills of Gascony, with its gentle, welcoming monks, is to come face to face with a tradition that still lives, that still calls to us, and that can still be our life, if we desire it — and if we have more courage than poor François.

One last thing: François failed to respond to his calling, but he at least understood what it would have to be if it was going to be real: total surrender. No half-measures. Nothing else works.

Only Rod could bang out something so profound (and profoundly at the heart of our present condition) on the way to the airport...

Your countenance expresses a transcendent joy that testifies to the presence of the Holy. Thank you.