Hi readers, it only just occurred to me — I am slow about these things — that I have a massive number of subscribers to this newsletter who aren’t on the paid list. For just over a year now, I have been sending this newsletter only to readers who pay for it. I ought to be sending a digest every now and then to you who would like to read, but who haven’t (yet, I hope) decided to fork over the five dollars per month (or fifty dollars per year) subscription cost. You who are paid subscribers can safely pass over this, because you will have seen it. For you others, here is a taste of what you’ve been missing. I hope you enjoy it.

Graham Greene’s Wallet

Someone, don’t know who, sent me a used book titled Powers of Darkness, Powers of Light, a 1991 book by the English journalist John Cornwell. Seeing Cornwell’s name piqued my attention. I recall that Cornwell is an ex-Catholic and ex-seminarian who published a highly controversial book years ago about Pius XII, with the slanderous title Hitler’s Pope. Normally I wouldn’t read a Cornwell book, but Powers details a simplified version of what I will be doing this year: traveling around looking at evidence for the miraculous, and inbreakings of the divine into our world. So I gave it a try.

The book, which I just finished, is disappointing in a way that it was destined to be, I suppose, though I’m very glad I read it because it’s an example of how this kind of book can go wrong. If credulity is one flawed approach to a project like this, then too much skepticism is another. The main lesson I took from the book is that unbelief is also an exercise in faith.

Cornwell doesn’t set out to be a debunker. His pilgrimage was inspired by a midlife curiosity about the faith that he had long ago rejected. There is, of course, nothing wrong and much right with approaching these things with skepticism. Yet you realize after a while that nothing is going to be able to breach the author’s tower of resistance, heavily fortified with English professional-class disbelief. Whenever Cornwell is faced with something he can’t explain, he always finds some rationalistic reason for it, or at least says that there is probably such an explanation. At other times he retreats in disgust at the vulgarity of the thing on display, as if God had offended him by showing Himself in such a trashy way.

I get that. It happened to me once. In January of 1998, my wife and I were on our honeymoon in Portugal, and made a side trip to Fatima to honor the Virgin Mary, and to thank her for her role in bringing us together. I had never been to a popular pilgrimage site, and had no idea what to expect. A bus from Lisbon dropped us on the outskirts of the village, a 90-minute drive north of the Portuguese capital. It was a cold, grey day. Julie and I tramped towards the cluster of buildings that indicated village life. But nobody was there. We had arrived in the depths of the off-season.

It was, we reckoned, the main street of Fatima. It was appalling. Religious tchotchke shops everywhere. One had glow in the dark plastic statues of the Madonna, in several sizes, filling a window. There was Fatiburger, and the John Paul II Snack Bar. This town lived off of religious tourism. It was gross. We checked into our hotel — I think we were the only guests — and then made our way towards the end of the street, to the vast plaza in front of the basilica.

There we saw a mass of pilgrims streaming into the church; it was January 8, a Marian feast day. It really did look like James Joyce’s oft-quoted line about the Catholic Church: “Here comes everybody.” As we stood at the edge of the crowd watching, a family approached from the right. There was a young Portuguese mother moving forward on her knees, with maybe a quarter-mile ahead of her. Here’s a photo from Google Earth of the plaza. Julie and I were standing towards the bottom left of this photo, on the north side of the white line, between the line and the trees. You can see how far that mom had to do on her knees to reach the basilica (upper right). She was doing this, mind you, in a cold drizzle, with the plaza asphalt damp under her knees.

Standing behind her was her husband, holding a baby, and an older woman — either her mother, or her mother in law. They were moving forward to thank God and the Virgin for the baby. The mom did not care about the hardship of “walking” on her knees, nor did she care what people might have thought of her. Such faith!

As I stood there marveling, I realized that judging by the modest dress of this family, they were probably the sort who would fill up the trunk of their car with tacky religious tchotchkes before heading home. And yet, upon whose heart — mine or theirs? — would the Lord look more favorably? To ask the question is to answer it. I repented.

This is not to say that standards of beauty are irrelevant. But it is to say that they should be considered in context. There is nothing more beautiful in the sight of the Lord than the gratitude and humility of that Portuguese family.

Anyway, back to Cornwell. He opens his book with an arresting anecdote based on an interview he did with the Catholic novelist Graham Greene. Cornwell visited him a year or so before his death in 1991. Cornwell questioned him on the nature of his Catholic faith, and found that Greene didn’t believe in much: not in heaven, not in hell, not in the devil, not in angels, and so forth. So why did he still call himself a Catholic? Because, Greene said, that he also doubts his disbelief. Then he told a story about Padre Pio, the great Franciscan mystic and stigmatist, who died in 1968.

“I am able to doubt my disbelief because I once had a very slight mystical experience. In 1949 I travelled out to Italy to see a famous mystic known as Padre Pio. He lived in a remote monastery in the Gargano Peninsula at a place called San Giovanni Rotondo. He had the stigmata, displaying the wounds of Christ in his hands, feet and side. At this time my belief in God had been on the ebb; I think I was losing my faith. I went out of curiosity. I was wondering whether this man, whom I had head so much of, would impress me. I stopped in Rome on the way and a monsignor form the Vatican came to have a drink with me. “Oh!” he said, “that holy fraud! You’re wasting your time. He’s bogus.”’ Greene looked up at me challengingly.

“But Padre Pio had been examined by doctors of every faith and no faith,” he went on. ‘He’d been examined by Jewish, Protestant, Catholic and atheist specialists, and baffled them all. He had these wounds on his hands and feet, the size of twenty-pence pieces, and because he was not allowed to wear gloves saying Mass he pulled his sleeves down to try and hid them. He’d got a very nice, peasant-like face, a little bit on the heavy side. I was warned that his was a very long Mass; so I sent with my woman friend of that period to the Mass at 5:30 in the morning. He said it in Latin, and I thought that thirty-five minutes had passed. Then when I got outside the church I looked at my watch and it had been two hours.”

Greene stopped for a moment as if to gauge my reaction.

“I couldn’t work out where the lost time had gone,” he went on. “And this is where I came to a small faith in a mystery. Because that did seem an extraordinary thing.”

He sat for a while in reverie. Then he took a well-worn wallet from his trouser pocket and fished out two small photographs. They were sepia, dog-eared. As he handed them over I detected a faint air of self-consciousness; as if, English gentleman that he was, he had been caught out in a gesture of Latin superstition. One depicted Padre Pio in his habit, smiling. The other showed the monk gazing adoringly at the host during Mass. The possession of the pictures, the gesture of sharing them, seemed a declaration of loyalty to faith.

“Why do you keep them in your wallet like that?” I asked.

“I don’t know why I put them in my pocket,” he said. He looked a trifle haunted. “I just put them in, and I’ve never taken them out.”

I decided to press him a little further. “If you hadn’t had your mysterious experience with Padre Pio might you possibly have lost your faith?”

“I don’t think my belief is very strong; but, yes, perhaps I would have lost it altogether…”

“So what, in the final analysis,” I said, “does religion mean to you?”

Greene looked at me directly, wonderingly. He seemed at that moment ageless; there was an impression about him of extraordinary tolerance, ripeness.

“I think … It’s a mystery,” he said slowly and with some feeling. “There is a mystery. There is something inexplicable in life. And it’s important because people are not going to believe in all the explanations given by science or even the Churches … It’s a mystery which can’t be destroyed…”

Greene’s dependence on that tiny sliver of belief brought to mind the case of Manfred, from Canto III of Dante’s Purgatorio. Manfred was an actual historical figure, a royal who died in battle, excommunicated from the Catholic Church. But he made it into Purgatory (which meant that he would eventually be with God in Paradise) because as he fell off his horse, mortally wounded, he repented.

As I lay there, my body torn by these

two mortal wounds, weeping, I gave my soul

to Him Who grants forgiveness willingly.

Horrible was the nature of my sins,

but boundless mercy stretches out its arms

to any man who comes in search of it…

…

The church’s curse is not the final word,

for Everlasting Love may still return,

if hope reveals the slightest hint of green.

For God so loves the world that He will accept the slenderest repentance — as think as the first green shoot of the spring — and draw us to Himself.

There is another story in the book, a written account by the novelist Tobias Wolff, a friend of Cornwell’s. Wolff tells the story about going to Lourdes in 1972, as a young man, wanting to volunteer to help the sick coming to take the waters. He explains that he has always had very poor vision, but hated wearing glasses, so he wandered through his youth in a blur.

Wolff spent some of his time on a crew of young men who stood in the grotto’s waters, lifting the sick out of their chairs and beds and immersing them in the bath. He saw the human body in all manner of agony. One day, his crew accompanied a group of disabled Italian pilgrims to the airport to catch their chartered flight home. Wolff’s assignment was to care for a completely paralyzed two-year-old girl, confined to her bed with tubes coming out of her nostrils, draining into bags under her blanket. It was hot and muggy as they loaded the plane, but then, for no apparent reason, the door to the plane closed, stranding the helpless child.

Wolff began to panic. The plane wasn’t moving, so he hoped that the door would eventually re-open. In the meantime, he did his best to keep the child cool. Flies discovered her face, and no matter how hard Wolff worked to keep them off of her, the insects harassed the toddler. Wolff says that he “became desperate with anger,” an anger that he realized was disproportionate to the situation. He was raging at the injustice of it all, at the cruelty of the world. When the plane door re-opened to let the child on, Wolff says he was sobbing, but as everybody was sweating buckets, nobody could tell.

On the bus ride back to Lourdes from the airport, Wolff, still not wearing his glasses, noticed that he could see things in the distance. He rubbed his eyes to clear them, thinking that maybe the mixture of sweat and tears had formed a kind of lens over his eyes that enabled him to see. But the effect didn’t go away.

I felt giddy and restless, happy but uncomfortable, not myself at all. Then I had the distinct thought that when we got back to Lourdes I should to to the grotto and pray. That was all. Go to the grotto and pray.

But he didn’t do that. The bus dropped him off at the barracks, where he fell into conversation with a gregarious Irishman he had befriended. Wolff didn’t tell him about the miracle, and was aware that he was hiding this from his Irish friend, who would have been interested, not judgmental. Wolff was aware this entire time that he was not going to the grotto to pray as he had been told to do. Eventually the two went to dinner, and Wolff never made it to the grotto that day. The next morning, his eyes were back to their broken state, and he had to wear glasses again.

Wolff tells Cornwell:

What interests me now is why I didn’t go. I felt, to be sure, some incredulity. But this wasn’t the reason. I have a weakness for good company, good talk, but that wasn’t it either. That was only a convenient distraction. At heart, I must not have wanted this thing to happen. I don’t know why, bu tI have suspicions. I suspect that I considered myself unworthy of such a gift. And if I had secured it, what then? I would have had to give up those doubts by which I defined myself, in the world’s terms, as a free man. By giving up doubt, I would have lost that measure of pure self-interest to which I felt myself entitled by doubt. Doubt was my connection to the world, to the faithless self in whom I took refuge when faith got hard. Imagine the responsibility of losing it. What then? No wonder I was afraid of this gift, afraid of seeing so well.

Incredible, isn’t it? Whoever among you sent me this Cornwell book, you have my thanks, because this Wolff anecdote is going into my book. That story illustrates one of the fundamental messages of the book: that we tell ourselves that we would believe if only we could see evidence for God’s existence, but in fact we prefer our blindness, because it gives us license to behave in ways we could not do if we were sure that God was real and watching over us. I have been there. Wolff was 27 years old when this happened — two years older than I was at my conversion. I spent my late teen years and the first half of my twenties telling myself that I would believe if only I had proof, but deceiving myself for the same reason that young Wolff did: because the “freedom” that I thought I deserved depended on nurturing my doubts. When you are at a party, and you have had a lot to drink, and you would like to go home with a cute girl you’ve been talking to all night, it’s amazing how vividly one’s religious doubts show themselves.

This is Cornwell’s problem in the book. Well, not necessarily the sexual aspect of it, but he clearly has so much invested in his worldview as a skeptic that by the end of the journey he chronicles here, I both pitied him and was quite annoyed by him. Annoyed, because it was clear that nothing he saw or heard would change him, because he did not want to be changed. Pitied, because he was plainly unhappy with his faithlessness, which is why he undertook the journey in the first place. It was clear to me by the time I finished Cornwell’s account that he was too afraid of the responsibilities that would come with losing his doubt.

In my book, I will be addressing this head on. I plan to visit Rocamadour, a medieval pilgrimage site in France. It is where the spiritual climax of Houellebecq’s novel Submission occurs. The dissolute protagonist François goes on pilgrimage there in a half-hearted attempt to regain his lost Catholic faith. In one of the worship services, François has a semi-mystical experience, and is at the very door of conversion … and then decides that he’s just hungry, and suffering from “an attack of mystical hypoglycemia.”

Everybody wants to get to heaven, but nobody wants to die. There is no telling how many people would have been saved, and could yet be saved, if they were not afraid of repentance, and did not care what other people would think of them.

Thoughts On The Feast Of Theophany (Baptism Of Christ)

Hiddenness, revelation, illumination: this is what Theophany is about.

I think it is also my favorite holiday because for each one of us, the experience of walking with God begins with theophany. Here, the Orthodox Christian ethicist Tim Patitsas describes faith as a “memory of theophany”:

Beginning [the search for God] with Beauty means beginning with feeling — not with passionate emotions or opinions, but with purified feeling. I mean a theological sensing, the innate ability we have to recognize theophany even in its hidden manifestation. In relying on that intuition, or in recognizing that within the Beautiful story of Christ is goodness, and therefore almost certainly truth, we fall in love with beauty and step out in faith toward it.

Is faith any different than eros? Abraham stepped out of his land and onto a journey of exile not because he worked it out intellectually but because he had received a theophany! Perhaps faith is just the memory of theophany, the continuing to launch out towards that divine supernova when it seems to have gone dark?

And when we find within Beauty the miracle of empathy, and contemplate this Goodness by imitating it, we see that the first feeling is not left behind. Rather, it is amplified and becomes contemplation, a feeling that includes discursive thought, or a faith that is expressed as reason. And finally our sense of truth is but an amplification of our sense of Beauty and our sense of Goodness or morality. The three are just one clear channel, one pure stream, flowing from feeling to contemplation to knowing Truth directly. this is why Orthodox theology looks the way it does, so pure and free, so elegant and aesthetically satisfying, rather than cold, logical, and hard.

The peerless Catholic poet Dante Alighieri, in Canto V of his Paradiso, has Beatrice instruct the pilgrim that all love begins with wonder inspired by theophany (because as the pilgrim Dante learns on his long, arduous pilgrimage, all the world is theophany pointing to the Creator). This is so beautiful:

“If I flame at you with a heat of love

beyond all measure known on earth

so that I overcome your power of sight,

do not wonder, for this is the result

of perfect vision, which, even as it apprehends,

moves its foot toward the apprehended good.

I see clearly how, reflected in your mind,

the eternal light that, once beheld,

alone and always kindles love, is shining.

And, if anything else beguiles your mortal love,

it is nothing but a remnant of that light, which,

incompletely understood, still shines in it.”

Standing in services tonight, I thought that an accurate title for this next book would be Theophany, though it probably sounds too churchy for the sales team. But that’s what it’s going to be about.

You will recall that Terrence Malick’s great but widely misunderstood film To The Wonder is one of my favorites. It is about love that begins in wonder, and how to hold onto it when the initial burst of light fades. Malick’s message is that we have to build structures — physical structures, and structures of habit — that keep the memory alive. If we don’t, we will be lost. The suffering Catholic priest played by Javier Bardem dwells in the darkness of abandonment, having lost his sense of God’s presence. Yet his faith — and it is a heroic faith — leads him to continue living by the memory of that initial theophany, and serving the poor. If you have never seen the glorious passage from the film in which the priest’s prayer is heard in voiceover as the camera follows him on his rounds, sit back and prepare to be stunned and uplifted, and to see God glorified through his faithful servant, Father Quintana. Here is the link.

I hope you all see God, the Father of us all, in a special way on this day. He is all around us, if only we had eyes to see. We are His beloved sons and daughters, and must not stand in His way, denying Him the chance to fill us with the wonder of His love.

Putting Medusa To The Sword

I went to confession last night for the first time in three months. I don’t think I’ve ever been so long between confessions. I apologized to my priest, both for that and for the fact that my confession was so brief. I explained that for the last eight or nine years, I have been carrying a heavy cross of angry nostalgia and resentment over the breakdown of my family in the wake of my sister’s death, and my unhappy return to my home. This cross was miraculously lifted from me when I made a pilgrimage to St. Galgano’s church in rural Tuscany this fall. The absence of that cross made me realize how many of my sins were tied to that unappeasable anger, pain, and humiliation.

It’s not that I suddenly became a model of virtue, I acknowledged. It’s just that I have to look harder into my heart for my sins, because the source of the ones I have been bringing to confession for almost a decade now is, by the grace and mercy of God, gone. I told my priest that I hadn’t come earlier, because after I got back from Italy, I kept waiting for the dark clouds to return, and to send me into despair, and sin. They never did, though. This hasn’t happened to me in eight or nine years!

“Yes, I’ve been able to tell in your countenance that things have changed,” said my priest. “You carry yourself differently.”

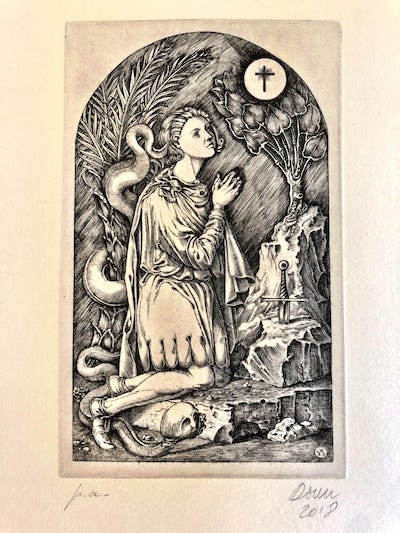

It’s really true. Nothing changed in my outer life … but everything changed in my inner life — or rather, was changed, because I did nothing but make a journey to pray at the place where the miracle depicted on an engraving a Catholic artist gave me in a Genoese church in 2018, on orders, he said, of the Holy Spirit.

I have been asking God for deliverance from this burden for a long, long time. Why did He answer my prayer in the affirmative on top of Montesiepi, under these circumstances? I will be pondering this for a while, but not too much, because the proper response to something like this is simple gratitude in the face of the benevolent mystery.

I have been thinking about the concept of flow since I began reading Iain McGilchrist’s new book, The Matter With Things. It occurred to me this morning that flow is how you could describe my experience of life since I came down off that little mountain in Tuscany. As I have written here many times, the crisis of the protagonist of Tarkovsky’s film “Nostalghia” — depression and creative paralysis over his heavy nostalgia — was also my crisis. I could not shake it, no matter how hard I tried. The message of the Tarkovsky film was that the key to his protagonist’s freedom was to get him out of his own head, to compel him to pay attention to something other than his own morbid thoughts of the past.

And so it has been with me. As we approach Christmas, I am thinking about all the gifts I have received this year, despite its difficulties, and this is the greatest one. If I think about why God might have healed me there, at Montesiepi, and not before, well, I did go on my knees and tell him that I will do His will, whatever it is, and asked him to show it to me, and to give me what I needed to fulfill my duty to Him. Whatever comes next will be because of that promise I made — a promise God knew that I meant with all my heart. And it’s because there is no way to separate my healing from the book project I am beginning: a book that aims to show to the world the reality of God’s living presence in the world, which is sometimes miraculous.

As I said, nothing has changed in my outer life, but I am no longer held captive by the Medusa stare of my past. Here’s a passage from How Dante Can Save Your Life that applies:

The malign power of the image is the next challenge Dante and Virgil face in Inferno. They approach the city of Dis, a citadel protected by walls of iron glowing red from the heat of the Inferno. Till now, the sins Dante and Virgil have faced are connected with the appetite. The iron walls of Dis symbolize that beyond this point, the sins punished are those having to do with a hardened will.

The demons guarding Dis will not grant them entrance. Virgil’s powers fail him for the first time on the journey. The pilgrim turns white with fear, but anxious Virgil bucks him up by telling him God has promised to send help.

Suddenly “three hideous women” appear, warning the two travelers to leave, or else they will summon Medusa, the monster from Greek mythology, whose gaze turns all those who meet it to stone.

“Turn your back and keep your eyes shut,” Virgil orders. He is so afraid for Dante that he puts his own hands over the pilgrim’s eyes to protect him.

The meaning of this dramatic moment has to do with the limitations of both intellect and the power of reason. Here at the gates of Dis, Virgil, sometimes considered the embodiment of reason, is up against a force too great for his considerable powers. Only divine assistance can save them now.

This Medusa moment has roots in Dante’s youth. Earlier in his life, the poet wrote a series of dazzling poems about the donna pietra, or stone lady. She was a heartless woman who would not return his obsessive love, thereby leaving his will powerless before her image. Here in Inferno, the pilgrim Dante faces a legendary woman with the power to freeze him in place with a single stare. And reason cannot help him conquer her.

We often underestimate our own weakness in the face of compelling images. In his Confessions, the fifth-century saint Augustine of Hippo wrote about his young friend Alypius, a Roman law student of strong moral convictions. His friends invited him to go to the gladiatorial games at the Colosseum, and after first refusing, Alypius agreed, saying that he would keep his eyes closed during the gory parts.

At the games, a roar from the crowd was too much to resist. Certain that he could handle what he saw without losing control over his will Alypius uncovered his eyes. It was a terrible mistake. Augustine writes:

He fell more dreadfully than the other man whose fall had evoked the shouting; for by entering his ears and persuading his eyes to open the noise effected a breach through which his mind—a mind rash rather than strong, all the weaker for presuming to trust in itself rather than in [God], as it should have done—was struck and brought down. As he saw the blood he gulped the brutality along with it; he did not turn away but fixed his gaze there and drank in the frenzy, not aware of what he was doing.

… The sudden appearance of an angel saves Virgil and Dante from the Furies and opens the gates of Dis for them. There are times when only an infusion of divine grace can give us the strength to overcome what we cannot conquer through our own power.

The showdown at the gates of Dis revealed to me my own personal Medusas: memories that rendered me helpless to act to free myself. Why was it that so many of my sessions with Mike [Holmes, my therapist] returned to the same family stories—the hunting trip, the bouillabaisse insult—and the same arguments, jibes, and rude gestures? And why did so many of my confessions with Father Matthew double back to those same stories?

My sins always emerged from anger at the unjust way I had been treated, and impotent rage at my inability to change my family’s minds or to overcome their power over my emotions. “The bouillabaisse story is the template for my relationship with my family”—if I told Mike and Father Matthew that once, I told them a hundred times. And it was true! But it had turned from an icon disclosing the emotional and psychological dynamics within the family system into a monster whose gaze I could not turn away from, and who turned my legs to stone.

“You think you can’t move,” Mike told me, “but those memories only have the power over you that you allow.”

“Do you think I want to hang on to them?” I said. “They’re making me sick as a dog, and miserable. If I knew how to let them go, I would. It’s not so much that those memories stick around, but that they explain so perfectly everything that has happened since I came back. One way or another, the bouillabaisse story happens every few days.”

“I get that,” Mike said. “I’m not denying that what you’re going through is real. What I’m saying is that you need to decide what you believe about memories. They aren’t who you are. They aren’t who you have to be. Even if things like this keep happening, and they likely will, you have to decide how much you will internalize them.”

I could see his reasoning, but I still did not know how to break the spell. I wanted a quick fix, a eureka moment that sorted everything out and set me aright. This was unrealistic.

Week after week, I would drop my son Matt off at his Thursday morning tutorial, then drive down to Mike’s office. I would tell Mike what had vexed me in the past week, and we would rationally analyze those events and anxieties in light of what we had established in our early meetings was true about myself.

The method worked something like this.

Me: My mother and father accused me of X this week.

Mike: Is it true?

Me: No, but they refused to listen to my explanation.

Mike: Okay, let’s break this down.

Then we would talk about the situation from several angles, including the possibility that the fault in the argument was my own. It frustrated me at first, because Mike wasn’t telling me what to do (nor, interestingly, does Dante; like an experienced therapist, he lets us arrive at these conclusions under our own power). We more or less talked about the same things week in and week out, without a firm resolution. It seemed so simplistic. If I was going to submit to this therapy thing, then I wanted to be bumrushed with applied psychoanalytic theory of the sort wielded by Viennese eggheads in hipster glasses, an intellectual adventure worthy of a novel and my grandiose sense of self. Instead, I was stuck there on that flowery sofa, washing dishes and peeling potatoes.

After a while, though, I began to see what the therapist was up to. He was applying psychoanalytic theory, but flying below my radar. The real work of therapy was taking place not in Mike’s office but in the hour after our meeting ended, when I would drive to a Starbucks and think about all that had been said. That’s when the firm resolutions began to emerge. That’s when I would decide in advance how I was going to act the next time one of these depressingly familiar clashes arose.

Eventually it became clear that Mike was showing me how to use reason to help me distance myself from the things that caused me such overwhelming stress. The rheumatologist had advised putting geographical distance between the stressors and myself. Mike was teaching me how to use reason and the growing power of my will, my free choice, to face down my own Medusas.

“You need to let your beliefs lead your emotions,” Mike said. “Once you see that you are free to choose your response to your environment, you won’t act so impulsively in regard to it.”

That made sense to me. I prayed constantly for God’s help, for the same divine assistance that rescued Dante and Virgil at the gates of Dis. In my exasperation, I was still hoping for a miracle. Only gradually did I see that healing grace emerging through the patient work my therapist and I did together.

That healing grace also emerged through study. As I read through the small library of books about Dante I had assembled, I discovered that in a version of the Greek myth told by the Roman poet Ovid—who influenced Dante greatly—Medusa was a once-beautiful woman who had been raped by Poseidon in the Temple of Athena, and as punishment made hideous by the furious goddess. Could it be that in the Commedia, the face of Medusa stands for something that was once a thing of beauty but had suffered corruption, and thus held a terrible power of fascination?

If so, then Medusa symbolizes the passions of Dante’s past and his inability to get free of them. Dante’s journey is a psychological one; the Medusa is the defaced image of a past obsession, one whose dark power threatens to end the entire pilgrimage.

Suddenly it hit me: my Medusa had begun as the beautiful dream of returning home to my family, a fantasy that had captivated and motivated me for years. When it finally came true in the wake of Ruthie’s death, I thought the realization of my dream was at hand. When it all turned sour and ugly, I was still captivated by the image of a loving, united family, but in a disfigured way that imposed a curse that I was powerless to defeat.

The Dantist John Freccero says that Dante’s Medusa symbolizes hardness of heart as an obstacle to conversion. In my confessions and our conversations in those days, Father Matthew acknowledged my hurt, but he also insisted that as a Christian, I could not be satisfied to rest in a place of resentment.

“You have to love them, no matter what,” my priest said. “Just as God loves you.”

“I know,” I told him. “I do love them. But it’s so hard to figure out how to love when it hurts so much and I’m so mad about everything.”

“It is,” he affirmed. “It will take time. Don’t stop fighting, though. Keep praying. Keep coming to confession. As long as you confess your sins sincerely, you’re in the arena fighting. It’s when you stop believing you have any sins to confess that the enemy has won.”

“But I haven’t done anything to them,” I said. “I came home for them. I wanted to be part of their lives. They didn’t want me.”

“Are you angry at them?”

“Yes.”

“Are you so angry at them that it interferes with your ability to show love to them?”

“Yes.”

“Then you are in sin, my friend.”

I thought about this for a moment. “I see your point,” I said. “In Dante, sin is a distortion of love. You’re saying that if my love for my family is distorted by my anger, then I am guilty.”

“You got it.”

This was a bitter truth that I struggled to choke down. I would confess my anger, but I could not yet master it, and did not understand why. But I sensed that deliverance from my personal Medusa would somehow come when I penetrated the mystery of why the dream of home had always been so potent in my mind. And I was certain that if I had any hope of breaching the iron walls that had broken my will on every prior assault, it was through prayer. So I prayed, and read, and waited, and followed Dante deeper into the pit.

The worst Medusa was eventually dispelled, but she returned in a milder disguise, and nothing I could do with my own reason could make her go away. When the demons refuse to open the gates of Dis for Virgil and the pilgrim Dante, God sends an angel to open it for them. I think that is what God did for me on top of Montesiepi. I haven’t felt this good, and confident, and excited about the future in a very, very long time.

In his new book, Dr. McGilchrist talks about how we create our own realities by what we choose to pay attention to. No, he’s not talking about some kind of New Age woo in which we control the world by our willpower. He is talking about how we have the power to choose how to respond to the world of phenomena into which we have been thrown. A misuse of that power, I think, is to decide to ignore phenomena that bring on negative feelings. That is to absent oneself from reality. To use it rightly, however, is to choose to affirm the good despite all the bad. This is the lesson Theophanes tries to teach Andrei in “Andrei Rublev”. This is the meaning of Luca Daum’s engraving, “The Temptation of St. Galgano”: Galgano is tempted to avert his gaze from Christ, to look to the ground, following the lead of a thought:

What joy to have been granted the graces necessary to lift up my head and see more clearly from Whom my salvation comes! I have never been more excited about a book project. This is why.

Speaking of flow, you might remember how, in this space, I talked a few weeks back about Mircea Eliade’s writing about the significance of the temple, and the mountain, as places of special communion with God. I went to a temple on top of a mountain, and all this happened to me. Whenever I’ve been tempted back to anger and despair since then, I bring to mind Galgano’s sword as a kind of sacred pole (something Eliade also discusses) connecting me to the energies of God. This has repeatedly brought me back from temptation to look down, so to speak, and returned me imaginatively to that experience of kneeling beside the sword in the stone.

This morning, I was thinking of it in McGilchristian terms, as a conductor of flow. What happened to me on top of Montesiepi was the restoration of flow in my life. Galgano made his life-changing connection to the flow of life-changing divine grace by plunging his sword into the stone. It is a symbol of the sacrifice of his life, giving it all over to God. If God really did call me to have some share of that sacrifice — and I think He did — then He is asking me to make a similarly radical surrender to Him. I believe that the months and years to come will reveal the meaning of that to me, though I already have a fairly clear idea what that might be. The point is that God has given me what I required to defy the gravity of the dead weight of an irrecoverable past, and freed me to serve Him more fully with a heart light and full of enthusiasm. It is all about attention, and how we are what we attend to.

Please do forgive me for focusing so much on the Galgano story. I just cannot express strongly enough what a big deal this has been for me. To wake up in the morning now with a heart eager to face the day is such a blessing.

Time And Space

When I have trouble falling asleep, I play a little mind game with myself. I imagine myself present in a war zone, but able to move at extremely fast speeds. I imagine moving fast enough to swat down with my bare hands bullets shot at my comrades. And then I am usually off to imagine other scenarios by which moving at extremely fast speeds makes everything else slow to a crawl. The other night I was imagining how moving at an extremely slow speed would make the life cycle of trees appear to pass in a mere moment. The mysteries of relativity are fun to contemplate.

The Say-But-The-Word Centurion

Here is a beautiful poem I discovered today by the late Australian Christian poet Les Murray. It’s based on this account from Matthew 8:

When Jesus had entered Capernaum, a centurion came and pleaded with Him, “Lord, my servantc lies at home, paralyzed and in terrible agony.”

“I will go and heal him,” Jesus replied.

The centurion answered, “Lord, I am not worthy to have You come under my roof. But just say the word, and my servant will be healed. 9For I myself am a man under authority, with soldiers under me. I tell one to go, and he goes; and another to come, and he comes. I tell my servant to do something, and he does it.”

When Jesus heard this, He marveled and said to those following Him, “Truly I tell you, I have not found anyone in Israel with such great faith. I say to you that many will come from the east and the west to share the banquet with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven. But the sons of the kingdom will be thrown into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

Then Jesus said to the centurion, “Go! As you have believed, so will it be done for you.” And his servant was healed at that very hour.

Here is the Murray poem, titled ‘That Say-But-The-Word Centurion Attempts A Summary’:

That numinous healer who preached Saturnalia and paradox

has died a slave's death. We were maneuvered into it by priests

and by the man himself. To complete his poem.

He was certainly dead. The pilum guaranteed it. His message,

unwritten except on his body, like anyone's, was wrapped

like a scroll and dispatched to our liberated selves, the gods.

If he has now risen, as our infiltrators gibber,

he has outdone Orpheus, who went alive to the Shades.

Solitude may be stronger than embraces. Inventor of the mustard tree,

he mourned one death, perhaps all, before he reversed it.

He forgave the sick to health, disregarded the sex of the Furies

when expelling them from minds. And he never speculated.

If he is risen, all are children of a most high real God

or something even stranger called by that name

who knew to come and be punished for the world.

To have knowledge of right, after that, is to be in the wrong.

Death came through the sight of law. His people's oldest wisdom.

If death is now the birth-gate into things unsayable

in language of death's era, there will be wars about religion

as there never were about the death-ignoring Olympians.

Love, too, his new universal, so far ahead of you it has died

for you before you meet it, may seem colder than the favors of gods

who are our poems, good and bad. But there never was a bad baby.

Half of his worship will be grinding his face in the dirt

then lilting it up to beg, in private. The low will rule, and curse by him.

Divine bastard, soul-usurer, eros-frightener, he is out to monopolize hatred.

Whole philosophies will be devised for their brief snubbings of him.

But regained excels kept, he taught. Thus he has done the impossible

to show us it is there. To ask it of us. It seems we are to be the poem

and live the impossible. As each time we have, with mixed cries.

—

“But there never was a bad baby” — what a beautiful way to write of the gift of newborn innocence Christ gives us through His grace.

“To have knowledge of right, after that, is to be in the wrong.” What a paradoxical line. What do you think Murray is saying here? My guess is that if the Law can murder God, lawfully, then how can those who know the Law be sure that they are righteous? What do you think?

To me, the most mysterious line is “But regained excels kept, he taught.” How cryptic. I think he’s saying that we can have all we have lost returned to us, through grace. But notice that what we have lost, and what we have returned to us, are not the things of this world, “the favors of our gods,” but lost innocence, a chance to begin again. This can be returned to you, Prodigal Child, and you can be at home again forever.

I keep reading this poem, drawing more from it each time. Les Murray believed that religion was poetry, and says so in the first stanza. Poetry does not operate by straightforward logic; it tells the truth slant.