So: on the TGV from Agen, in far southwest France, to Paris. Taxi from Montparnasse station to Charles de Gaulle, then flight to Budapest. Get home around midnight. Wash clothes. Dry underwear and dress shirts with an iron (no dryer in my flat). Repack. Leave flat at 5 am for airport to fly to the US. Such is my life these days. I guess it’s a real First World Problem: “Oh, the agony of traveling so intensely because people want to hear what I have to say!” Still, I’m too old for much more of this.

That said … WHAT a time in the countryside near Agen, at the traditionalist Catholic monastery of Sainte-Marie de la Garde, a daughter house of the big monastery Le Barroux! It’s a new-ish place, much of it still under construction. As you might have seen in this story that I posted last week, the monks foresee it as a modern refuge — modern, only in the sense that it will be constructed for the 21st century. The traditional Latin mass and the monastic devotions remain untouched.

Père Abbé (Marc) and his prior, Père Ambroise, greeted me with warmth and affection. It turns out that The Benedict Option (in French, Le pari benedictin) was a big hit in France; most of them know the book. Some trad Catholics in the US remain resentful that I left the Catholic Church, and only speak ill of me, but these monks know I am a friend of theirs, and of Western monasticism, and seek to celebrate it and to promote it in my writing. Their monastery is in the hilly countryside near the town of Agen. Here is the view from in front of the monastery chapel:

After quickly settling into my room, I joined the abbot and Gen. Stéphane Abrial, a retired senior NATO general — in fact, in 2009 he was appointed the Supreme Allied Commander Transformation — for a tour of the grounds. Gen. Abrial is a great supporter of the monastery, and is leading a fundraising campaign for it. The monks do woodworking and make sandals in their shops on the property. I saw their chapter house, and then their impressive library, with tens of thousands of volumes. Out back there is lots of construction going on. These men are building for the long term. They told me a number of Catholic families from all over France are buying property in the rural region, to be close to the abbey. Yep, sounds like a Benedict Option is in full swing here. Here’s a link to the abbey’s website, in French.

Talking with the abbot, I recalled a saying of Balzac’s, which goes something like, “Hope is memory plus desire.” That is, if you remember something good, and you desire it intensely enough, you may find the hope to recover it. That seems to me like a good motto for the work of Sainte-Marie de la Garde. Honestly, if I were a Catholic who had the funds to support this monastery’s construction, I would give whatever I could. They are building a lighthouse in the present darkness, and in the darkness to come. Whatever happens elsewhere in France, this abbey will be a stronghold of the faith, and, in time, of a community of the faithful. (If you want to donate to their capital campaign, and can read French, click here. If you want to donate but can’t read French, email me at roddreher (at) substack (dot) com, and I’ll pass it on.)

Later, we drove into nearby Agen for a conference about Living In Wonder. The hall filled with local people, who had come to hear me butcher their beautiful French language in my prepared remarks. They provided me with a local translator for the Q&A, a sweet, plump elderly dame of great dignity, who told me she learned English by working for English-speaking companies.

I got the talk out somehow, and then questions began. It quickly emerged that Madame did not speak English very well at all. I was alarmed by the look on the faces of English speakers in the audience. I don’t have much French, and it was impossible for me to follow Madame’s words at all, given her quiet, slurry voice, which reminded me of a fading camellia. After some time, people in the audience raised their voice to correct her. At first I was quite irritated by this, but I ended up feeling quite sorry for her, and even admiring her, for she carried on with her back straight and her jaw set, even though she surely understood she was making a botch of it.

As in every other conference I’ve ever given in France, people wanted to know why I left the Catholic faith. I can always tell that my answer never satisfies them. I guess it couldn’t possibly do: they believe it is the True Faith, and don’t understand how anyone, having found it, could depart. I always try to convey to them the truth: that though I can no longer be Catholic, I admire much about the Catholic faith, and even love it, and see my role as building bridges from Orthodoxy to Western Christianity. I told them that I would love it if more people would convert to Orthodoxy, but more than anything else, I want people to come to Jesus, and those who are already Christian to live more fully for and in Christ.

It is my sense that in Europe, Christians rarely leave their birth religion for another form of Christianity. In the US, this “churn'“ is a huge part of American Christianity. I think this must be something of my generation and later; I think of my father, who carried a huge chip on his shoulder about the Methodist church for most of his life, but would not consider for one second changing denominations. It seemed bizarre to him, and a betrayal of one’s roots. “I’m not going to let them drive me out of my church!” he thundered, for decades. Daddy carried his grudge into the grave, refusing even a church funeral. But by God, they didn’t run him out of his church!

This reminds me of a little ditty he taught Ruthie and me in our childhood:

Ma and Pa went to the circus.

Pa got hit with a rolling pin.

Ma and Pa got even with the circus:

They bought tickets, but they didn’t go in.

After the discussion, I went to the table to sign books, and to meet the local folks. One man told me that it is more or less forbidden in France to make a link between crime rates and migration. “But if you walk around here,” he said, meaning the town, “everybody knows the truth.” As in Paris, I picked up lots of fear among conservative Catholics that a civil war is coming, over migration, Islam, and the Great Replacement. One of my interlocutors, citing a senior official in the security services (obviously I won’t give his name), quoted the official as saying, “It is no longer a question of if, but of when.”

As in Paris, the Catholics down here in la France profonde were buzzing about how all over the country, churches were full on Ash Wednesday. Some folks were content simply to give thanks for it, but others suspected that it has a lot to do with the rise of Islam. People are afraid, and they sense that now is the time to return to their ancestral faith. I think this is why Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the Muslim apostate, began her journey into Christianity from atheism. Like historian Tom Holland, Hirsi Ali realized that most of the things she cherishes about Western liberal democracy come from a Christian basis. Judging by her speech at ARC, Hirsi Ali seems to have started her path to Christianity from an instrumental basis (i.e., defending the West), but her faith has become real. It must, because asserting Christianity as a mere defensive identity will not work, and worse, it could turn into something like the Catholic and Protestant terrorists of Northern Ireland, whose faith was merely an excuse to commit violence and murder against their enemies.

Back at the abbey, I settled in to dinner in the guest kitchen with Père Abbé Marc, Père Ambroise, the General, and Beatrice Doyer, my doughty, fun-loving publicist — a Catholic mother of six who lives in the Vendée with her husband, and who is exactly the kind of dame you want at your side in the fight. In Paris I had taken to calling her “Mère Abbesse”. It fits.

We had a long, rich conversation, about affairs of the world, in the church, and in the world of the spirit. Mère Abbesse’s roaring laughter kept us all delighted. I observed the monks addressing the humble and dignified military man as “mon Général,” which I did too, and felt very Grand Illusion about it.

I asked the monks how they chose the monastic life. Père Ambroise told me that he comes from a large, old Catholic family in Grenoble. As a younger man, he considered serving in the military, or as a monk. He chose the monastery. It occurred to me that often when I meet young Catholics in France, priests and laity alike, a surprising number of them come from “old Catholic families,” and many of them also have strong traditions of military service. Talking to someone in Paris last week, I mentioned what an English Catholic friend recently said to me: that civil war is coming for all of Europe, but the French will survive (in his view), while the English nation will not. “They have a culture,” the Englishman said. “We do not.”

My Parisian interlocutor told me that the fact that there remains in France, despite her many faults, a strong culture of family might well be the thing that gets the French through. Listening to Père Ambroise talk about the culture of his family, and how it prepared him for monastic life (or would have done for military life), I understood better what the man in Paris meant.

Lying in the stillness of my cell after dinner, I reflected on how the sense one gets at Sainte-Marie is one of overwhelming tranquility. You can feel it. You really can. It feels very, very far away from the world. This sense is also quite present in the character of the two monks who spent time with me, the abbot and the prior, as well as my driver, Père Isaac, a Quebecois monk. How I would have loved to have spent an entire week with them all!

Earlier in the conversation, the abbot asked me about J.D. Vance’s conversion, and his life as a Catholic. I told him and the others that when J.D. told me he wanted to become Catholic, I found a reliable Dominican in Washington to do his instruction, and that J.D. had invited me up to Cincinnati to be present at his reception into the Church. Aside from that, though, I don’t really know, but I believe he is steady and faithful.

Père Abbé asked me to tell the vice president that the monks will devote themselves to prayer for him. He said that in some real sense, he (the abbot) believes that J.D. Vance has the future of France in his hands. Overnight he sent me a note that said,

We will take the opportunity to keep your friend in our prayers, so that he may serve the Lord in truth and faith through this delicate and difficult mission, which can nevertheless bring great good to his country, and ultimately to all.

Up for mass this morning, I found the chapel absolutely packed, and spilling out into the adjoining hall with worshipers. I didn’t want to be rude, but I could have stared for a long time at their faces. The gentleness of these country people, and the soft but intense piety. I thought about this young man, François, I met in Paris. He mentioned that he converted to Christianity (from nothing) after listening to Jordan Peterson’s lectures on the Bible. He will soon be going to seminary, for the traditionalist Fraternity of St. Peter. “I hope one day Providence allows me to thank Jordan Peterson for what he gave me,” François said. Well, I told him, Providence has visited you this morning; I know Jordan, and would be happy to record a message from you, and send it to him. I thought he might faint dead away, but he collected himself and allowed me to film a message that might have been spoken by the dear cleric in the Bresson film version of Diary Of A Country Priest. Here is a still from that message, which I sent to JBP. The look of purity and youth in the kid’s face says it all. Those eyes!

The mass this morning was, of course, the Tridentine mass, with Gregorian chant. When the monks chanted the Kyrie, I closed my eyes and allowed it to flow into my heart. Those holy words were like an eagle soaring over the hills and valleys of my heart. I was able to follow the service with an English-Latin missal. It was surprising to discover that the TLM uses Psalms as much as we do in the Orthodox Church. A traditional priest I met on this trip asked me if I ever went to the TLM in the US, when I was a Catholic. Yes, I said, but I found myself put off in part by the palpable anger and rigidity of the congregations. They seemed quite mad at the Church, and I saw that as a temptation for me, as I was at the time also fighting anger. A very conservative Catholic (but not a tradi, as they call them here) who sympathizes with the tradis chimed in to say she has seen the same thing in some TLM parishes here in France.

Well, there was none of that spirit of all in this monastery today. The congregation were young people with small children, middle aged people, and the elderly. Praying with these Catholic brothers and sisters in Christ, I felt intensely why people like this love the Old Mass, and felt a wave of anger and sadness both rise up in me, over the fact that the tradis are so persecuted by their own Church, and the Pope. On the other hand, I guess the renovationists of the Vatican II generation understand well the threat this mass poses to their progressive utopia. I suspect that any young Catholic who experiences the kind of transcendence and solemnity of the Gregorian mass celebrated this morning on that hilltop would find it very hard to return to business as usual. In my book, I write about how one cannot force enchantment to happen, that the most we can do is to prepare ourselves so that when a comet blazes across the sky (that is, God gives us a sign of His presence), we can recognize it and react to it. Believe me, a comet crossed the hilltop this morning, and I am confident that all those who worshiped this morning left better prepared to perceive God’s presence in their own worlds in the week to come.

Today’s Gospel reading was St. Matthew’s account of the Transfiguration. What a perfect illustration of what I mean by Christian enchantment! Atop Mount Tabor, Peter, James, and John saw Our Lord surrounded by light, and attended by Moses and Elijah. That is, they observed with their eyes the full truth of reality. To be enchanted as a Christian, then, is to live in the awareness that all the world is, in some sense, a Tabor, if we were able to see it as it really is — and to act out of that awareness. I thought of the pilgrim Dante asking Beatrice, on the journey, why he cannot see her in the fullness of her glory. She warns him that if she revealed herself to him in that state, he would not be able to bear the light. In Orthodoxy, we believe that the more pure you make your own heart, the better able you are to perceive the presence of God. So, if you want to experience Christian enchantment, purify yourself. Easy to say, hard to do. Believe me, I prayed this morning about my own struggles with my sinful heart. Lent is the special time for that, isn’t it?

Earlier, when I talked to Père Abbé about the role of traditionalist monasteries in today’s Catholic Church in France, he spoke with genuine charity about how he tries to build bridges of fraternity with all Catholics. This impressed me, as sometimes tradis I know are palpably contemptuous of their Novus Ordo brethren (again, this is one big thing that kept me from becoming a TLM-goer in my Catholic days). What a blessing it was to listen to the abbot speak from a place of great love. A blessing, and an example.

After mass, Mère Abbesse took me to a room near the monastery shop, where I signed copies of my books for massgoers. One couple, in early middle age, asked me, in English, why I moved to Hungary. After telling them, I mentioned, in a jokey way, that French Catholics keep urging me to move to France.

“No!” they exclaimed, in unison.

“That would be a bad idea,” said the husband, firmly. He explained that France is in deep crisis, and it’s going to be getting worse.

“Hungary is an oasis of sanity,” he said. His wife nodded vigorously. He added, “I’ve been there only on business, and it was a real shock to me to discover that Budapest is like what the rest of Europe was thirty or forty years ago.”

He’s talking about mass migration, of course. Honestly, Americans who haven’t been here and lived here — meaning, gone outside the historic, touristed centers — have no idea at all how migration has transformed and is transforming European life. The more time I spend in western Europe, observing this, the more I understand why the European political and media class have to demonize Hungary: ordinary Europeans must not be allowed to think of Hungary as an example of the kind of lives they can enjoy if they had governments that would put a stop to mass migration, as the Orban government has.

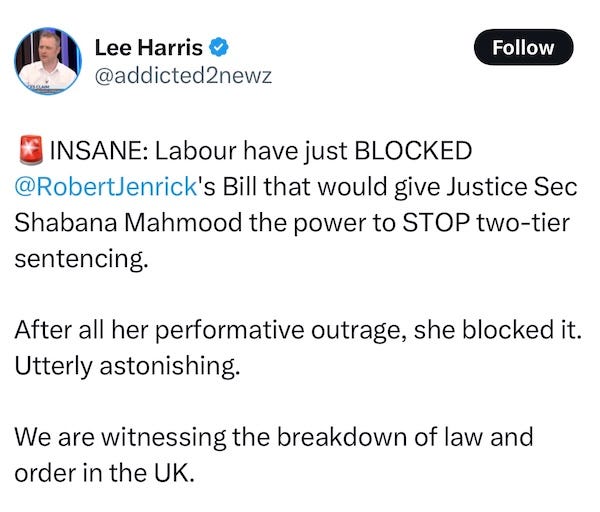

Saw this on X today:

So now Britons know that the Labour government is totally committed to enforcing a harsher standard of law on white Britons. How can the people tolerate that? Not long ago, an outraged British woman, talking with me about the possibility of the British Army engaging in Ukraine, told me, “I will not see my sons fight for this tyrannical government.” With each passing day, I understand this better.

American readers, are you getting any of this information in your mainstream media? I bet not.

In that National Catholic Register story about this abbey, its prior said:

“It is certainly an ambitious project, but one that remains reasonable,” Brother Ambroise commented, “because we know that monasteries will be called upon to play an ever-greater role in future times, and it is up to us to show a thoroughly Christian boldness to rekindle hope in hearts. … We have no pretensions but immense conviction!”

Yes, they will … and yes, these monks do. Their warm hospitality and generosity of spirit really moved my heart and stirred my imagination. Hope is rising in the Garonne! What a gift to have been able to witness it, and participate, however briefly, in this monastery’s life.

Alors, on to Budapest, then to America. Paris last week was as frenzied as any book tour I’ve ever had, so it was an absolute blessing to end my voyage here at the traditionalist monastery. When he said goodbye to me, Père Ambroise looked me directly in the eyes, and said, “This is your home. You are always welcome here.” I knew without a doubt that he meant it. And I also knew that I would be back.

How happy this essay made me. So encouraging to know they are there, praying.

As an aside my church now has seventeen katechumans-- one more just today-- and that's after we chrismated eleven at Christmas and seven last year at Easter. We've had two whole families come to us this winter: a young couple with a baby, and a family with two teenagers (the son came to us first and brought his parents and sister). When they are all in attendance and come forward for a blessing during the Litany Of The Katechumans there are almost too many of them to fit the space available.