And that is how I spent my Thanksgiving: in the company of the Monks of Norcia, in a manner of speaking. It was a very good day.

We invited a few friends over for dinner al fresco. We set up long tables under the carport, so we could be outside. We sat everyone some distance apart, which was weird and unpleasant, but better that than not getting together at all. We bought a smoked turkey, but otherwise Julie and I cooked everything else: roasted carrots with herbs, cornbread dressing with gravy, brussels sprouts with bacon, celery root rémoulade, Dorie Greenspan’s Pumpkin Stuffed With Everything Good, and homemade cranberry sauce with satsuma zest. What else? There must have been something else. There was so much food! Nora made pumpkin chocolate chip bread, and crème brûlée. Julie made an apple pecan pie. We had Birra Nursia (blonde), Sancerre, Burgundy (Nuits St-Georges), and an Australian Shiraz. I had a bottle of Bordeaux (Pomerol) on back-up, but we finished neither of the reds.

How strange it is to get older (I’m 53), and renegotiate my relationship to food and drink. I only ate about half of what I would have eaten in even the recent past, and drank maybe half a bottle of wine, then wished I hadn’t, because all that food and drink makes me feel worn out and logy, but not in a good way. Even though I eat less than I did, I’ve gained a lot of weight during Covid, which is, I guess, from my metabolism changing. Good food and good drink make me so happy normally, but I seem to be losing my capacity to enjoy them like I used to. I can’t figure out why. Maybe it’s just being a bit depressed from this lousy year, and the endless Covidtide. But I think it’s deeper than that. I have been many things in my life, but ascetic is not one of them. Hence my befuddlement. When did too much stop being not enough, and just enough started feeling like too much? Mysterium tremendum…

Back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, I loved a band out of Austin, Poi Dog Pondering. They had a song called “Thanksgiving” that naturally came to mind today — the chorus was “Thanksgiving for every wrong move.” The whole song goes like this:

Somehow I find myself far out of line

From the ones I had drawn

Wasn't the best of paths, you could attest to that

But I'm keeping on

Would our paths cross if every great loss

Had turned out our gain?

Would our paths cross if the pain it had cost us

Was paid in vain?

There was no pot of gold, hardly a rainbow

Lighting my way

But I will be true to the red, black and blues

That colored those days

I owe my soul to each fork in the road

Each misleading sign

'Cause even in solitude, no bitter attitude

Can dissolve my sweetest find

Thanksgiving for every wrong move that made it right

I found myself thinking about the song, and the wrong moves I’ve made in my life that turned out for the good. The big one, as my regular readers know, was moving back to Louisiana in 2011 for what I thought was going to be a happy homecoming. It didn’t turn out that way at all, and I never saw that coming. If I had known what was waiting for me back home, I never would have made that move. But if I hadn’t, I would never have confronted the dragons hiding in my own heart, and never had to fight them to the death. I never would have been reconciled at a deep level with God, and with my dad. I would not have been able to live with him in the last week of his life, and hold his hand as he breathed his last. I would not have felt that all of it was golden. I would to this day still be broken and guilt-ridden because I had not been around for the end of his life. And I would not know God as I now do. As hard as the last nine years have been in many ways, I can say thanks for that wrong move.

Another wrong move I made that turned out well was leaving Washington for south Florida in 1995, to take a job in arts journalism. I loved my life in DC, but felt a strong calling to move to Fort Lauderdale for the job — this, despite the fact that I really don’t like the beach at all. There were very clear signs that I needed to do this, against my own will, so I did.

I was terribly unhappy. My job was great, I loved the people I worked with, but I did not fit in south Florida, even though it was a beautiful part of the world. Some people are beach people, but I am not. I was a fairly new Catholic then, and desperate for a parish community, which I could not find. I also was very, very eager to find a girlfriend, but it was a romantic desert for me, for reasons I can’t explain to my own satisfaction. I had been there for a year and a half when I took a trip to Austin, and there I met the woman I knew from the first weekend we were together that I would marry. We became engaged after four months, and lived out our betrothal period half a continent away from each other. Not long after we married, I had a job offer in New York City, and off we went.

I was able to see in retrospect that the intense loneliness I had in Florida was a time of deep transformation, such that if I had not had to live in that spiritual desert, I don’t know that I would have matured enough to be able to recognize the worth of the woman God chose for me to marry. That experience taught me that even times of suffering can be working a hidden alchemy on our souls that we will only be able to discern in retrospect. This is a valuable lesson.

Can you think of any wrong moves (not necessarily geographical) for which you are thankful today? I’d love to hear about them and publish them here. E-mail me at roddreher — at — substack — dot — com.

The historian Tom Holland reminded me today of a lovely website that I used to frequent, but foolishly forgot about: A Clerk of Oxford, written by Eleanor Parker, an Oxford-trained medievalist who loves to write about medieval England. (You can get her Journey Through The Anglo-Saxon Year on her Patreon, but you have to pay a small amount for it; I think I’m going to do this, because Tom Holland says it’s really good.) Parker doesn’t write much on her blog anymore. I found from an August entry a beautiful poem from the 14th century that she translated. Here are a couple of stanzas in the original, followed by her translation:

But leve we oure disputisoun,

And leeve on him that al hath wrought;

We mowe not preve bi no resoun

How he was born that al us bought;

But hol in oure ententioun,

Worschipe we him in herte and thought,

For he may turne kuyndes upsedoun,

That alle kuyndes made of nought.

When al our bokes ben forth brouht,

And al our craft of clergye,

And al our wittes ben thorwout sought,

Yit we fareth as a fantasye.

Of fantasye is al our fare,

Olde and yonge and alle ifere.

But make we murie and sle care,

And worschipe we God whil we ben here.

Spende our good and luytel spare,

And eche mon cheries othures cheere.

Thenk how we comen hider al bare;

Our wey wendyng is in a were.

Prey we the prince that hath no pere,

Tac us hol to his merci

And kepe our concience clere,

For this world is but fantasy.

Bi ensaumple men may se,

A gret treo grouweth out of the grounde;

No thing abated the eorthe wol be

Thaugh hit be huge, gret, and rounde.

Riht ther wol rooten the selve tre,

Whon elde hath maad his kuynde aswounde;

Thaugh ther weore rote suche thre,

The eorthe wol not encrece a pounde.

Thus waxeth and wanieth mon, hors, and hounde,

From nought to nought thus henne we highe.

And her we stunteth but a stounde,

For this world is but fantasye.

Her translation of these stanzas:

But let us leave our disputations,

And believe in him who made all things.

We cannot prove by any reason

How he was born, who redeemed us all;

But, whole in our intention,

Let us worship him in heart and thought,

For he may turn nature upside-down,

Who made all nature out of nothing.

When all our books are brought out,

And all our clerkly skill,

And all our wits are sought all through,

We still pass as a fantasy.

Of fantasy is all our faring,

Old and young and all together.

But let us make merry and put by care,

And worship God while we are here;

Spend our goods and spare little,

And let each man encourage another to be cheerful

Think how we came here entirely bare.

Our way wends on, we know not where.

Pray we that the Prince who has no peer

May take us wholly to his mercy,

And keep our conscience clear,

For this world is but fantasy.

By this example you may understand:

A great tree grows out of the ground,

And the earth is not a tiny bit diminished,

Although the tree is tall, big and round.

The tree will still be rooted there

When old age has brought down his kindred;

Though there were three such trees rooted there,

The earth will not be enlarged by any degree.

Thus wax and wane man, horse, and hound,

From nothing to nothing from hence we fly,

And here we stay but a little while;

This world is but fantasy.

Isn’t that beautiful? Parker’s commentary includes this passage:

This poem has been in my mind lately, partly because I find a bit of medieval wisdom poetry helps a lot when everything is so unrelentingly sad. So many, many good things have gone in the past few months and they're probably never coming back, so it's genuinely useful to be reminded that always and everywhere, 'wo is ende of worldes wele'. Of course. What else is to be expected? Something about this particular poem's emphasis on 'fantasy' also seems an apt way of describing our strange 'new normal', where the virtual world, absent and insubstantial, is supposed to take the place of so many of the forms of tangible human contact we once knew and relied on. The fantasy of the virtual world creates the illusion of bringing people before us, but the moment the screen goes black they vanish into nothingness, much swifter than the flight of a bird. You're still alone in an empty room. And if virtual life isn't that, it's social media, with its hate and anger and violence, lurching from one crisis to the next, full of people utterly unwilling to extend kindness or understanding to strangers when they can shout at them instead. That's fantasye as phantom, nightmare. For me, real-life contact with other human beings is ordinarily what stops all that from becoming overwhelming, and makes it flee away like a bad dream. Often, one little friendly interaction with a stranger on the bus or in a shop has been enough to give me hope that most people aren't really be as awful as they seem on the internet. But that's gone; those harmless interactions are impossible now. Smiling faces are hidden, life's little grace notes of sympathy are silenced, while the howling roar of virtual rage goes on louder than ever. Well, that too isn't really new, but just the same endless wrangling which this poem warns against. 'Each side thinks the others rave'... A horrible new normal all this may be, but there's nothing new under the sun.

Here we are at Thanksgiving, in no better condition. But there must be a blessing in all this, though it may take a long time to perceive it. Anyway, the beer was delicious, and so was everything else at our table tonight. The company — the first people to have been to our home for a meal since March — was generous and kind, despite our distance. Whatever wrong moves this world has taken this year that threw us into this slough, the way we respond to this suffering now will determine whether in years to come, we can give genuine thanks for a severe mercy.

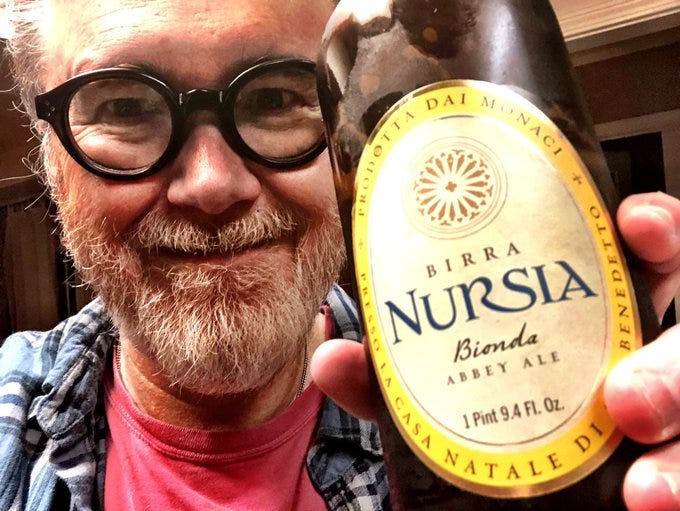

If you wish to gladden your heart with delicious monastic beer, I encourage you to buy Birra Nursia online, if you live in the US. They will deliver it to your front door in a matter of days. I prefer the blonde, which is lighter and crisper, but if you like malty ales, the Extra, at 10 percent alcohol, will bring blush to your cheeks. If you find yourself in Italy sometime when this accursed Covid ends, why not go visit the Monks of Norcia? These Benedictines are good men doing holy work there on the side of a mountain in Umbria, overlooking the hill town where St. Benedict was born in 480. Among their good deeds: brewing Birra Nursia (incidentally, buying their beer supports the work of the monastery). Here is Brother Augustine Wilmeth, a man of South Carolina, who has become a monk and a brewmaster:

Here is a link to a chant by the Norcia monks, with gorgeous video of the little town before it was ravaged by the 2016 earthquake. If you read my book The Benedict Option, which has a chapter devoted to these men, you’ll remember that it ends with the earthquake, like this:

Five days later, more earthquakes shook Norcia. The cross atop the basilica’s facade toppled to the ground. And then, early in the morning of Sunday, October 30, the strongest earthquake to hit Italy in thirty years struck, its epicenter just north of the town. The fourteenth-century Basilica of St. Benedict, the patron saint of Europe, fell violently to the ground. Only its facade remained. Not a single church in Norcia remained standing.

With dust still rising from the rubble, Father Basil knelt on the stones of the piazza, facing the ruined basilica, and accompanied by nuns and a few elderly Norcini, including one in a wheelchair, he prayed. Later amateur video posted to YouTube showed Father Basil, Father Benedict, and Father Martin running through the streets of the rubble-strewn town, looking for the dying who needed last rites. By the grace of God, there were none.

Back in America, Father Richard Cipolla, a Catholic priest in Connecticut and an old friend of Father Benedict’s, e-mailed the subprior when he heard the news of the latest quake. “Is there damage? What is going on?” Father Cipolla wrote.

“Yes, damage much worse,” Father Benedict replied. “But we are okay. Much to tell you, but just pray. I am well, and God continues to purify us and bring very good things.”

The next morning, as the sun rose over Norcia, Father Benedict sent a message to the monastery’s friends all over the world. He said that no Norcini had lost their lives in the quake because they had heeded the warnings from the earlier tremors and left town. “[God] spent two months preparing us for the complete destruction of our patron’s church so that when it finally happened we would watch it, in horror but in safety, from atop the town,” the priest-monk wrote.

Father Benedict added, “These are mysteries which will take years—not days or months—to understand.”

Surely that is true. But notice this: the earth moved, and the Basilica of St. Benedict, which had stood firm for many centuries, tumbled to the ground. Only the facade, the mere semblance of a church, remains. Because the monks headed for the hills after the August earthquake, they survived. God preserved them in the holy poverty of their canvas-covered Bethlehem, where they continued to live the Rule in the ancient way, including chanting the Old Mass. Now they can begin rebuilding amid the ruins, their resilient Benedictine faith teaching them to receive this catastrophe as a call to deeper holiness and sacrifice. God willing, new life will one day spring forth from the rubble.

“We pray and watch from the mountainside, thinking of the long three years Saint Benedict spent in the cave before God decided to call him out to become a light to the world,” wrote Father Benedict. “Fiat. Fiat.”

Let it be. Let it be.

A couple of years later, Father Benedict told me that the monks had a new birth of passion for God in the wake of the destruction of their church and old monastery. He said that they did not know how much they needed the silence of living outside the town to aid their search for God until their church and monastery on the piazza fell to rubble. For the monks, who lost almost everything in the earthquake, God brought forth blessing. I need to ponder this more than I do.