The Bruderhof & The Benedictines

Reader reflections on modern Anabaptists, and Christmas greetings from Norcia

Y’all like my Christmas tree? Ignatius doesn’t live there all the time, but he does dwell on the adjacent shelf. I think he brings proper theology and geometry to the Christmas spread here at my house, and if you disagree, I shall lash you with a lute string.

Forgive me for having no Deep Thoughts tonight. I am working hard to finish a big essay on Christopher Lasch, and I can’t think of anything but the revolting elites tonight. Besides, the mailbag overfloweth with correspondence about the Bruderhof, and about Christmas carols. So y’all are writing my newsletter tonight.

About the Bruderhof

Several letters about last week’s “With The Bruderhof” post about the modern Anabaptist community.

From a neighbor of the Fox Hill Bruderhof:

I live close to the Hudson Valley's Bruderhof community, and have been wondering who these "Amish Lite" people are. I used to see them in the local KMart before that closed. Now I have an idea of who they are and what they believe in. I find it interesting that you wrote that they believe in left-wing "issues like racial justice and serving the poor...and they are pacifist". There is something wrong in today's conservative Christianity if these values are seen as "left-wing". Just because the anti-religion left has embraced racial and economic injustice does not mean that we should abandon them.

True — that’s why I pointed out that I hesitate to characterize those values as left-wing, but I wanted to make clear to readers that moral conservatism can exist alongside what normally passes for social liberalism. This would not be surprising to Europeans, but here in the US, very many of us on both sides of the spectrum believe that these are dissonant.

Another reader:

When I saw you mention the book Salt and Light, I remembered seeing it in our bookcase. It was a book my husband bought, so I asked him about it.

I'd forgotten that years before we met, he considered joining a Bruderhof community. He was at a point of time in his life when he was becoming a committed Christian and he wanted to live in community with other people who shared that goal.

He never went down that path, not because he didn't want to give up his worldly comforts, as per the rich young man you spoke about, but because similar to you, he had lived long enough to realize that notwithstanding idealistic visions of building a utopia, we are all flawed humans that will undoubtedly corrupt everything we do.

He thought they had shut down years ago. But when I researched further and explained where the various communities are currently located, he was glad to hear they are still operating.

Here’s a reader in Cambodia:

[Quoting the original post:] "The thing you notice about the kids there is how unmarked they are. There is an innocence and wholesomeness that is almost out of a storybook. This is what childhood is supposed to be about. It comes, you realize, from being raised without television and pop culture. They play outside, with each other, safely. It’s so strange to find this strange."

Your observation here resonates with me. But I think it's possible to do this, to have kids like this, without being part of a distinct, separate community. It requires saying no to a lot of things kids think they want, and also saying no to a lot of things that we as parents think we want: time to ourselves, lots of movies, digital babysitters, and so on. But it's mostly yes: yes to lots of time with the kids, yes to games and family reading, yes to risk -- since kids who play outside and climb trees and make fires are exposed to some risk. But it's nothing like the risk of kids being on social media or having a teacher who hates the good and the beautiful wants our kids to hate them too.

Maybe I'm a bit disingenuous saying that this is generally possible. I have no idea how this kind of life is possible in a city, or in a home where both parents have to work long hours to survive, or in a single parent home.

And honestly, withdrawing from society helps us, too, even if we aren't part of a commune. My wife and I have six kids (our newest addition came last month), and we live as Baptist missionaries in northeast Cambodia -- I'm a Bible translator. The nearest English-speaking families live about 45 minutes to our west. Our kids are well aware of the world, and its joys, and its neuroses. But since they aren't in a school with peers pressuring them to do unhealthy things and have unneeded things, our job is a lot easier.

When I sat down to write this, I was watching five of our kids gathered around a little fire in the yard, boiling beans in old tin cans from the recycle bag. Now they're starting a game of cops and robbers with two girls from the village behind our house. Yesterday my 8-year-old son had a nice kick fight with some of the neighbor boys (he explained that you just just stand around kicking each other's legs, and trying not to get kicked -- since everyone wears flip-flops, it's not so bad I guess). Our kids are pretty happy, and lively, and very interested in the world.

This is how we would have tried to raise our kids if we'd stayed in Texas, where my wife taught in a Title 1 school in Dallas before our first was born. But it would have been harder, and there weren't any climbing trees at the apartments where we lived, and I bet they wouldn't like the fires.

A short, sweet letter:

It sounds pretty great actually. If I weren't married I might actually go and live there and help them.

The older you get, the less you care about your own deal.

A deep letter from a reader who used to be a regular commenter on my blog:

As you may recall, I lived for 10 years in a place that aspired to be like the Bruderhof, and was in many ways: a so-called "covenant community" similar to People of Praise. My answer to your question of whether I could trade autonomy for community is no, I could not. The first thing I thought of was Huck Finn: "But I reckon I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she’s going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can’t stand it. I been there before."

When I was in the community, I was horribly depressed. This was partly for pre-existing reasons, but greatly exacerbated by the fact that things that used to alleviate my depression--reading and writing--were impossible to do there. I was a young mother with no money, which would have made it hard in any case. However, in community, time was almost completely scheduled up with community activities and service jobs that required all one's energy. There was nothing left over for art, study, or poetry.

I had a talk with my "handmaid"--yes, we called them that--about my relentless depression. I showed her a handful of my poems, just to let her know that I actually could write and wasn't just blowing smoke about having a creative gift. Weeks went by with no response, and when she handed them back to me at last, I said "So what did you think?" She just shook her head and said, "I feel sorry for you."

That rankled me for YEARS. I felt so humiliated and angry that I had shared something close to my heart, and all I got back was a pitying shrug. Many years after we left the group, I had an opportunity to reach out to this person again. By then, she too had left the group, and had suffered some great losses, which softened my heart toward her. I was ready to stop being angry. We reconnected with kindness and grace, in what I can only believe was a gift of God.

She said that she had come to believe that what she used to teach about submission to authority had done people harm, and she greatly regretted that. She explained that she hadn't meant what I thought. She had seen my work for what it was and had not despised my abilities. Rather, she felt sorry for me because she couldn't see any way that what I wanted to do could ever fit into community life. There was just no place for me there unless I could give up on all that and simply conform myself to community ways.

I don't consider myself a great artist by any means, but I am as God made me. Near the end of our time in community, I dreamed repeatedly that I was being murdered, that I was dying. And that was true, in some sense. It's not just autonomy that you sacrifice in such a community. I don't believe you can have art and that level of conformity. I don't believe in the myth of the artist as a crazy nihilist rebel either, but for creativity to thrive, there has to be a degree of freedom and individual choice that isn't possible in the Bruderhof.

You can't even have a hobby in a place like that. They don't allocate the resources or time for that. Not only is there no art, there's no ham radio, no model train layouts, no gourmet cooking classes, no wine tastings, no fencing clubs, no garage bands, no travel, no opera performances, no ballet, no theater. Just thinking about it makes my chest tighten and I feel as if I'm suffocating. People aren't meant to be that much alike! I mean, if you are that kind of person, more power to you, but it was killing me.

I can't believe God really wants a world without art. Hopkins said that God fathers forth "all things counter, original, spare, strange." There's just no room for the counter, original, spare, or strange in Bruderhof World. There's not only no room for art, there's no room for God's beloved eccentrics, to whose ranks I think you and I may both aspire to ascend.

Yes, there are many virtues in their life. But there's a darker side, too. Tolkien said it best. "Gandalf as Ring-lord would have been far worse than Sauron. He would have remained righteous, but self-righteous. He would have continued to rule and order things for 'good', and the benefit of his subjects according to his wisdom (which was and would have remained great). . . . Thus while Sauron multiplied . . . evil, he left 'good' clearly distinguishable from it. Gandalf would have made good detestable and seem evil."

When you truncate human beings and human experience to such an extent, even in the pursuit of good, you're going counter to the freedom it seems that God has decided to allow. You risk doing evil in the pursuit of good, and then human beings, in their finite perception and their grief and pain, will often feel that this evil you did in God's name came from the hand of God Himself, and they will believe God to be evil. That's not a negligible risk.

Another one:

I think you are correct, about authority being required for the kind of deep, rich and intertwined community you see with the Bruderhof. Community comes on a spectrum with the Bruderhof style communities on one end, requiring strong authority (wholesomely wielded by the grace of God) and atomized non-community on the other end with little authority. My immediate family and I live somewhere in the middle, probably towards the richer side with our midsize non-denominational church (pre-COVID ~300 on a Sunday morning). We do not have the kind of commanding authority you'd expect at Bruderhof, but I have seen and experienced that the investment of time can also produce rich community. Here are two stories to share the richness that does happen in our community.

First a sad story: We had a family in our community of two parents with two elementary age boys. The Tuesday before Thanksgiving this year, the parents were killed in a fiery car crash. One of their sons was with them and miraculous escaped unharmed, while the other was with his grandparents. Needless to say, this tragedy has rocked our little church and the small Christian school the boys attend and where the Mom taught. But it is here that one sees both the value of deep community and the love of Christ shining brightly. This family had another family that the parents were close with and the kids of both families are friends. With the grandmother's approval (she does not live in our town), this family has taken in the orphaned boys. This allows the boys to stay with a family they know and like and continue at the same school and church. The larger community has rallied around these boys as well. It has been barely a month, but I know at least the following facts: Furniture and moving of the boys stuff into their new home was taken care of almost immediately. The family now has a shed someone built for them in their backyard. The memorial service was at (COVID) capacity of 200. I don't know how many people watch in the overflow room or online. A meal calendar was set up that runs through March and is already full! That is four months of meals! I don't expect the estate had much money in it, but last I heard nearly $50K has been raised for the boys in about a month. It has been beautiful to witness the body of Christ in action in the midst of this tragedy.

A second and happier story is my own wedding five years ago. I had been at the church roughly 14 years (yes, I married late in life) and had actively invested in the community there resulting in good relationships with much of the church. First, I volunteered with elementary age Sunday school, even though I had no kids and was single. Later, I volunteered (eight years, I think!) with the high school youth group (which is not like some of the awful ones mentioned on your doom and gloom blog). I've also been part of various weekly small groups over the years (never more than one group at a time). All of this investment and time meant that my wedding was large and happy because we invited many families from the church and many came to celebrate with us along with many of their children.

All of this community exists because people at our church invest time with each other. We make it a priority. I suppose you could argue that there is an earthly authority that contributes to this community: our pastors (currently just two ordained men), the board of directors/elders and various lay pastors. But this authority does not exercise the same kind of authority that you likely find at a place like Bruderhof. I know of one instance in my 19 years when someone has been asked to leave the church because he was causing some sort of damage to the community, but that involved the pastors and the elders and the person ultimately was asked to leave and did so peaceably.Ultimately, it is the love of Christ that draws our community together and we prioritize spending time together outside of Sunday worship. After church on a Sunday, come onto the play ground behind the church and you'll always see kids playing while the adults talk.

I'm sure our community is not as deep and rich as that at Bruderhof, but it is a far, far cry from the atomized non-community so many experience. And the authority being less than that at Bruderhof, probably makes it an easier place for many community starved Americans to join. But without a commanding authority, this community must be built with the investment of time and lots of it! That means commitment to one place and people, which many Americans are scared to make.

A Catholic reader:

I would like to think I would join them…if they were Catholic, anyway. I was thinking about a comment you’ve made in the past, about how, for you, the only viable options for you as a Christian are Catholicism and Orthodoxy, because they are “totalizing” faiths. There is a depth to these that other Protestantized forms of Christianity lack. I don’t know much of anything about the Anabaptists (this is piquing my curiosity, though), so I can’t speak to the depth of their theological and liturgical practice, but it seems like their faith gets lived out in a much more radical fashion - there is clearing something different about the way they live, in a way that cannot be said of us Catholics or Orthodox. I wonder if perhaps Anabaptism (whether Bruderhof, Mennonite, or Amish) is perhaps a totalizing religion in a different way than our own, with a much stronger focus on how one lives and not just how one believes. There is a lot of potential depth in Catholicism, but, to borrow a phrase from CS Lewis, and is been found demanding and left untried.

Another reader:

The Bruderhof sound like a fascinating community. They, the early Christian communities, and the Kibbutzim make me think that "communism" can work among small groups with a strong moral fabric. If I create something of value that the community sells successfully in the wider world, it may not increase my personal wealth that much, but it could pay for a new school building in which my children could study. In a communist state of tens or even hundreds of millions of people, though, I would never see the benefits of my endeavors except very indirectly. It would make me feel like I am being squeezed dry by a giant.

I wouldn't be a good fit for the Bruderhof either because the extremes of my spiritual desires tend more toward hermit-hood than toward being in a cloister of sorts. This is one reason why I, guiltily, have not been that perturbed by the day-to-day experience of the pandemic.

A New Hampshire reader:

I just finished reading your Substack piece this morning and many things resonated with me. I actually contacted Bruderhof yesterday and immediately received a warm and welcoming reply from one of their women. Thanks for the ref!

Many times, when I consider the lives of Mennonites or Amish and such, I feel a sense of call. I know for a fact that we don't need most of the things we take for granted in modern life. Yet, like you, I can identify with the 'rich young ruler' in Scripture. I may not have a lot of stuff, but I do have a strong, self-willed, control-freak self to deal with. Would I be able to leave it behind to follow a life that could promise the Christian community I seek? They are going to find me a pen pal in the Bruderhof Hudson Valley community. We shall see. I am in my early 70s, alone, unmarried my entire life, living in subsidised housing, concerned about facing persecution for the Faith alone, as well as care in advancing age. Could this be the answer? The best answer available? Could I give up my hand-poured, paper-filter coffee?

It’s the little things, isn’t it? I know exactly what she means.

Another reader:

The Bruderhof has many characteristics of early Christian life in its voluntary sharing of goods with those who need them. It’s a way of life socialism tries to impose, ultimately always unsuccessfully. Pacifism may be of Christ, I’m not sure, but no bigger society can survive with this belief at its center. Years ago, I asked a reader of your blog who’s a pacifist, if he thought retaliation for Pearl Harbor was justified, and in a long response, he said no.

Not many will be called to this lifestyle. It’s perfect for those called, like those called to a Benedictine monastery, but few will be called to it. To the larger world, it’s a light and beam of grace that holds up to the rest of us the purity and beauty of an unadulterated Christian witness. It calls us to more radical living within our own circumstances, much as Norcia does. We don’t have to be called to that community, but we can incorporate aspects of the community in our lives. Thanks for this.

A Christmas Card From the Norcia Monks

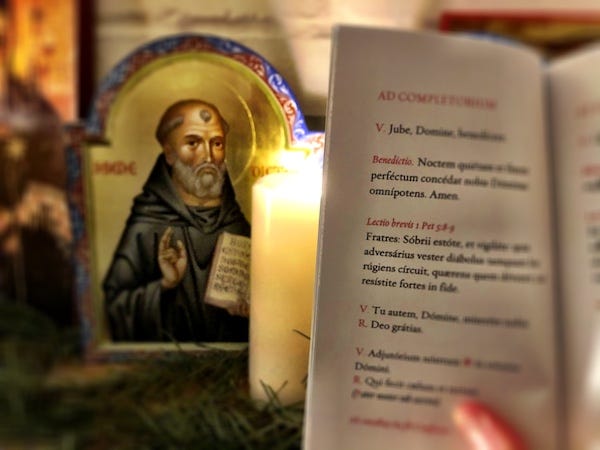

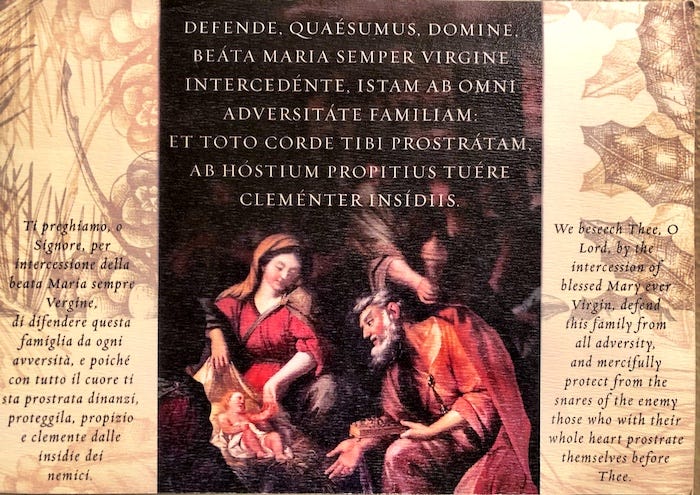

Speaking of Norcia, I received a Christmas card today from the Monks of Norcia, along with a beautiful booklet of Latin and English compline prayers. Funny, I dreamed of them last night, and this morning the card came.

I see that the Norcia monks have done a new podcast with the editors of the Jesuit magazine America, talking about brewing beer for God. I haven’t heard it yet, but I wanted to post it here for y’all. I just took the photo at the top of this section of one of the prayers from the prayerbook, in front of my icon of St. Benedict, written (the icon; one doesn’t “paint” an icon) by Fabrizio Diomedi, the iconographer of Norcia. Fabrizio painted all the frescoes in the refectory — all destroyed by the 2016 earthquake. To mark the completion of my book The Benedict Option, which centers in part on the Benedictines of Norcia, I commissioned a diptych of St. Benedict of Nursia and St. Genevieve of Paris, two saints to whom I have a devotion, and whose prayers I asked often as I worked on that book.

Fabrizio completed the diptych, and presented it to me in San Benedetto del Tronto, when I last visited the Tipi Loschi. That’s the Adriatic in the background:

It gladdens my heart to think of all these friends in Italy, both lay and monastic. Though I am not a Catholic, I love telling everybody about the Monks of Norcia. Longtime readers of my blog might remember this video appeal I posted there in 2015. Justin Leedy was a young American who discerned a calling to a monastic vocation, but needed to retire his student loan debt before he was free to act on it. Leedy’s case was taken up by the Labouré Society, a Catholic charitable organization that works to pay off student loans for Catholics who want to pursue a vocation to the priesthood or life in a religious order. Here is the appeal Justin Leedy made to donors, asking them to retire his loan debt so he could go to Norcia and test his vocation:

It worked. A few weeks back, I received a handwritten letter from Justin Leedy — unaccountably delayed for months, lost in the mail — telling me that he had made his vows as a Benedictine this summer, and was now a monk of Norcia. He thanked me and my readers for their generosity, because it made his vocation possible. He enclosed this souvenir of his official entrance into the monastery as a vowed monk:

How about that! This young man is now a monk, because so many people, most of whom he never has met, and may never meet, cared enough to pay off his student loans. Good things do happen. There are more young people that the Labouré Society is trying to help, and that you Catholic readers may wish to assist with your Christmas giving. And, the Monks of Norcia take vocations inquiries from Catholic men aged 18 to 30. If I were young and Catholic, I would be thinking about a monastic vocation — and my first thought would be of Norcia, a solid, orthodox, and growing community right there on the side of the mountain, in the shadow of which St. Benedict grew up.

Sorry, folks, but I’ve got to get back to my Lasch essay. No Christmas carol opinions here tonight. Hey, this newsletter is still free. You get what you pay for.