The Crack In The Tea-Cup

And the strangeness of the good: On the restorative powers of poetry and art

I am grateful for the e-mails I receive from readers of this newsletter, telling me that they are enjoying it, and that they especially appreciate the way I use this format to try to find reasons for hope amid the gloom of the day’s headlines. Believe me, this is a good spiritual and moral exercise for me too. It is so much harder to write this little daily newsletter than to publish my blog, precisely because cause for hope is quieter, more modest, and more fragile these days than the causes of despair.

Part of that is my own temperament. I have never been a gloomy person, but I have a strange disposition towards the … well if not quite the apocalyptic (though there is that), then at least what you might call bad news. Maybe that’s why I became a journalist. Good news doesn’t often make the papers. After all, if the train arrives safely at the station 999 times, that is not news; it’s the one time it goes off the tracks that makes the front page. Harmony and happiness is what we seek, or so we tell ourselves, but secretly we are drawn to bad news — and not just because we have a perverse streak.

“The malaise has settled like a fallout and what people really fear is not that the bomb will fall but that the bomb will not fall.” So said Walker Percy, in his novel The Moviegoer. Percy said that people secretly love hurricanes, because when everything is at risk, then you know who you are and what you are supposed to do. I wrote last night in this space about how the most charmed and charged time of my life was living in New York City in the fall of 2001, after the September 11 attacks. It was so rich and beautiful and heartbreaking that I shudder thinking of how much life seemed to mean then. Percy captures the feeling in this passage from his nonfiction Lost In The Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book:

Imagine you are a member of a tour visiting Greece. The group goes to the Parthenon. It is a bore. Few people even bother to look — it looked better in the brochure. So people take half a look, mostly take pictures, remark on serious erosion by acid rain. You are puzzled. Why should one of the glories and fonts of Western civilization, viewed under pleasant conditions — good weather, good hotel room, good food, good guide — be a bore?

Now imagine under what set of circumstances a viewing of the Parthenon would not be a bore. For example, you are a NATO colonel defending Greece against a Soviet assault. You are in a bunker in downtown Athens, binoculars propped up on sandbags. It is dawn. A medium-range missile attack is under way. Half a million Greeks are dead. Two missiles bracket the Parthenon. The next will surely be a hit. Between columns of smoke, a ray of golden light catches the portico.

Are you bored? Can you see the Parthenon?

Explain.

In related news, Blaise Pascal said, “All of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” Yes, without checking his Twitter feed.

Since at least 1993, when I first recall reading it, I have loved Auden’s great poem “As I Walked Out One Evening.” It’s a poem about suffering and powerlessness, but its clever, lively rhymes conceal the depth of its insight. A poem that sounds so breezy can’t possibly be so heavy, you may think at first reading.

It’s a poem about Time, symbolized in various forms in the poem as water. It begins with the romantic vision of youth, with light-hearted young lovers feel that what they have is eternal, like a rushing river. Then:

But all the clocks in the city

Began to whirr and chime:

'O let not Time deceive you,

You cannot conquer Time.'In the burrows of the Nightmare

Where Justice naked is,

Time watches from the shadow

And coughs when you would kiss.

Later, these lines, so vivid, almost like a witch’s incantatory curse:

'The glacier knocks in the cupboard,

The desert sighs in the bed,

And the crack in the tea-cup opens

A lane to the land of the dead.

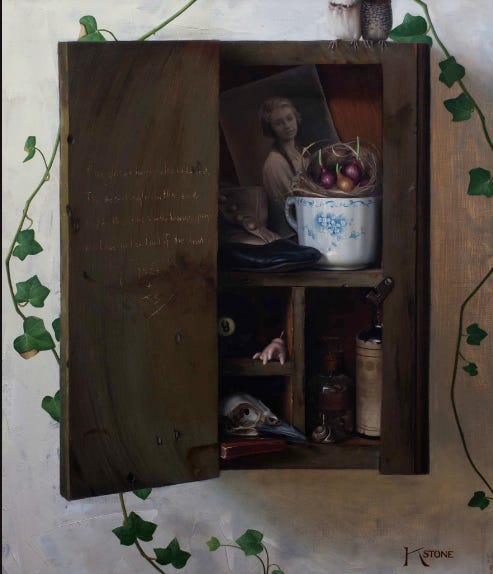

(The Canadian painter Kate Stone has painted a still life — see above — that incorporates that verse. You can see the painting up close, and even buy it, here.)

In that stanza, Auden uses hyperbole and jarring imagery to symbolize how the things of ordinary life — the cupboard, the bed, the tea-cup — can contain portents of our demise. If water is time in this poem, then this stanza is about the inability to predict or control time. Time can be like a glacier (a frozen immensity) or like a desert (where water is immensely not present). A cracked tea-cup leaks, making an icon of cozy domesticity into a memento mori.

What can set the world right again? Gratitude and mercy.

'O look, look in the mirror,

O look in your distress:

Life remains a blessing

Although you cannot bless.'O stand, stand at the window

As the tears scald and start;

You shall love your crooked neighbour

With your crooked heart.'

In an earlier stanza, the poet instructs the reader to stare into a basin — a symbol of man’s futile attempt to keep time from flowing — “And wonder what you’ve missed.”

Notice what the poet does in these two, though. Looking at one’s reflection in a wash basin, in the earlier lines, does not provide a clear image of one’s face. If I’m reading him correctly, Auden is saying that when we perceive our image as bound to time, it is smeared by longing and regret. What’s more, the poet’s order to plunge one’s hands into the basin “up to the wrist” seems to me to be an allusion to suicide, one possible response to despair. But to look not into the basin but into a mirror is to perceive ourselves as we are, not as we might have been. And so, “Life remains a blessing/Although you cannot bless.”

What a remarkable line. You are exhausted, spent, broken — and yet, you live! Life remains a blessing — not “is” a blessing, but remains one, even after the cost of it is tallied. It is a proclamation of faith, and hope — actually, of hope through faith in the fundamental goodness of life.

Then, the reader is told to turn from the mirror to the window, to look out at the world beyond. The final image of water: hot, shocking tears, wrung from grief, the shared fate of us all. Thus the command: “You shall love your crooked neighbor/With your crooked heart.” Crooked here means bent, unstraight — your heart has been broken by time — but it also connotes sinfulness.

What becomes of the broken-hearted? They must love — or die.

Auden was a great poet, and indeed a great Christian poet. You may not know this about him, but he began his return to the Anglican faith of his childhood in 1939 while living in New York City. He went to a movie theater in Yorkville, at the time a neighborhood on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Auden’s biographer wrote:

It was largely a German-speaking area, and the film he saw was Sieg im Poland, an account by the Nazis of their conquest of Poland. When Poles appeared on the screen he was startled to hear a number of people in the audience scream “Kill them!” He later said of this: “I wondered then, why I reacted as I did against this denial of every humanistic value. The answer brought me back to the church.”

Auden intuited that the only force strong enough to resist radical evil was belief in God. Auden discovered what the older poet T.S. Eliot meant when he wrote in the same time period:

As political philosophy derives its sanction from ethics, and ethics from the truth of religion, it is only by returning to the eternal source of truth that we can hope for any social organization which will not, to its ultimate destruction, ignore some essential aspect of reality. The term “democracy,” as I have said again and again, does not contain enough positive content to stand alone against the forces that you dislike—it can easily be transformed by them. If you will not have God (and He is a jealous God) you should pay your respects to Hitler or Stalin.

I found the discussion of Auden in the Yorkville theater in this blog post. The follow-up post talks briefly about Auden’s re-conversion in adulthood. Auden, of course, was gay, and did not live by Christian orthodoxy in his sexual life. And yet, he believed. He could offer no rational account of his faith (because it was faith), but Auden believed. He said later in his life:

…if I hadn’t been a poet, I might have become an Anglican bishop – politically liberal, I hope; theologically and liturgically conservative, I know.

Here’s another reason why it is a good but difficult exercise for me to write this newsletter. I was earlier in my life a professional film critic. The late critic Roger Ebert once explained that it’s easy, and fun, to write bad movie reviews. Here’s a paragraph from the master himself, dismissing a 1988 picture called “Last Rites”:

Many films are bad. Only a few declare themselves the work of people deficient in taste, judgment, reason, tact, morality and common sense. Was there no one connected with this project who read the screenplay, considered the story, evaluated the proposed film and vomited?

When you find a film that is exceptionally good, it’s a lot more challenging to identify why it works so well. Here is Ebert doing that in his four-star review of “Lost In Translation”:

Bill Murray's acting in Sofia Coppola's "Lost in Translation" is surely one of the most exquisitely controlled performances in recent movies. Without it, the film could be unwatchable. With it, I can't take my eyes away. Not for a second, not for a frame, does his focus relax, and yet it seems effortless. It's sometimes said of an actor that we can't see him acting. I can't even see him not acting. He seems to be existing, merely existing, in the situation created for him by Sofia Coppola.

Is he "playing himself"? I've known Murray since his days at Second City. He married the sister of a girl I was dating. We were never friends, I have no personal insights, but I can fairly say I saw how he behaved in small informal groups of friends, and it wasn't like Bob Harris, his character in the movie. Yes, he likes to remain low key. Yes, dryness and understatement come naturally to him. Sharing a stage at Second City with John Belushi, he was a glider in contrast to the kamikaze pilot. He isn't a one-note actor. He does anger, fear, love, whatever, and broad comedy. But what he does in "Lost in Translation" shows as much of a reach as if he were playing Henry Higgins. He allows the film to be as great as Coppola dreamed of it, in the way she intended, and few directors are so fortunate.

She has one objective: She wants to show two people lonely in vast foreign Tokyo and coming to the mutual realization that their lives are stuck. Perhaps what they're looking for is the same thing I've heard we seek in marriage: A witness. Coppola wants to get that note right. There isn't a viewer who doesn't expect Bob Harris and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) to end up in love, or having sex, or whatever. We've met Charlotte's husband John (Giovanni Ribisi). We expect him to return unexpectedly from his photo shoot and surprise them together. These expectations have been sculpted, one chip of Hollywood's chisel after another, in tens of thousands of films. The last thing we expect is… what would probably actually happen. They share loneliness.

It goes on, but really, Ebert has said it all. He was far from the best writer among the top critics — that would be Anthony Lane of The New Yorker — and I didn’t always trust Ebert’s judgment. But when he was on, he really could see to the heart of a movie, and tell you why it worked. And he, unlike most critics, was more fun to read when he loved a film. When Ebert hated a movie, he left you with the impression that his indignation was like that of a lover who caught his partner shagging a pimple-faced pothead. It wasn’t only the betrayal of something sacred, but the bad taste in so doing.

Anyway, good poetry and good movies, like all good art, recalibrates the inner eye. When you cannot bless, art reminds you that life remains a blessing. The crackle of Auden’s verse, like the martini-dryness of Bill Murray’s wit, open up a lane back to the land of the living — if we are capable of sitting still quietly in a room alone, and receiving what the artist reveals to us.

Here is a poem titled “Through The Water.” It appears in The Strangeness Of The Good, the new collection of poetry by James Matthew Wilson, which takes its title from a line below. He is a Catholic who teaches literature at Villanova, and an extraordinary writer, as you can see in this poem, a striking companion to Auden’s “As I Walked Out One Evening.”

We must in some way cross or dive under the water, which is the most ancient symbol of the barrier between two worlds

-Yvor Winters

Far back within the mansion of our thought

We glimpse a lintel with a door that’s shut,

And through which all our lives would seem to lead

Though we feel powerless to say toward what.

It is the place where all the shapes we know

Give way to whispers and a gnawing gut.And so, in childhood, we duck beneath

The waterfall into a hidden cove;

In summer, pass within a stand of pines

Cut off from those bright fields in which we rove,

Whose needles lay a softening bed of silence,

Whose great boughs tightly weave a sacred grove.When winter settles in, and our skies darken,

We take a trampled path by pond and wood,

And find beneath an arch of slumbering thorn

Stray tufts of fur, a skull stripped of its hood,

Then turn and look down through the thickening ice

In wonder at the strangeness of the good.And Peter, Peter, falling through that plane,

Where he had only cast his nets before,

And where Behemoth stalked in darkest depths

That sank and sank as if there were no floor,

He cried out to the wind and felt a hand

That clutched and bore his weight back to the shore.We know that we must fall into such waters,

Must lose ourselves within their breathless power,

Until we are raised up, hair drenched, eyes stinging,

By one who says to us that, from this hour,

We have passed through, were dead but have returned,

And are a new creation come to flower.