The Hidden Heroes

'If a man thinks that God has abandoned him, it is not true. He is only hiding'

On my TAC blog today, I had a couple of long posts about despair and disintegration in both the Evangelical (see here) and Catholic (see here) churches. As I always try to make clear, there are elements of the crisis of Christian faith that are specific to particular churches and traditions, but these are indeed parts of a general crisis. No church or religious tradition in modernity, especially in the West, is going to escape it.

In the Catholic one, I linked to the pointed response to the McCarrick Report by the Catholic theologian Larry Chapp, who criticized the 400-page document as a cold bureaucratic attempt to make the anger and concern over the rise of the lecherous former cardinal go away. Chapp derided the “de facto atheism” of the Church, saying that men who behave like this, and who won’t own up to what they’ve done, live as if God doesn’t not exist.

Here’s a screenshot from Catholic News Agency’s J.D. Flynn, summarizing on Twitter answers from today’s USCCB press conference:

Structures! Programs! Protocols! That’ll fix everything. We’ll nail down the policies and procedures so tight that nobody will have to be holy to be good!

I mean, honestly. Honestly. Here’s a quote for you:

''This crisis is more important than any crisis we've had in my time. Our people are waiting for the bishops to say, O.K., we've got it under control, we're on the same page, we hear you and we've listened to you and now you can be sure that this will never happen again.''

Know who said that? Cardinal Ted McCarrick, on June 12, 2002.

In response to my Evangelical post, this heartfelt e-mail came:

I think I'm one of those young people. I'm 29, and I recently left my church I had been growing distanced from because of MAGA when the pandemic sent people off the deep end. Misconduct and conspiracy theories nearly drove me to suicide.

I'm picking up the pieces with Kent & Rosaria Butterfield now, trying to figure out where to go from here. I'm still not 100% sure I believe in Christ anymore. I had always been the first to say that the conduct of Christians doesn't control the truth or falsehood of Christ's resurrection. But I'm trying desperately to cling on now.

1. If Christians will believe anything, if their discernment is so sick, what about the resurrection? If Christians are so stupid, what if the disciples were too, and they're just delusional about the resurrection?

2. I thought Christ was supposed to discipline his Church. What about Hebrews 12 discipline? 1 Corinthians 11 discipline? Acts 5 discipline? Where is that? It's not the actions of Christians themselves that bother me ... but the apparent inaction of Christ. I want to scream at God and demand him to discipline his Church or else. And if that discipline and judgement has to start with me, at least I'd feel loved --- that's what Hebrews 12 is about.

It's stupid of me. You know you should fear God. You know that when you say that ... it's the extreme version of "Be careful what you wish for ... because if you ask God for patience, he might teach it to you the hard way." Who knows what I could bring on myself?

But I just want Daddy to treat me like a son.

My heart breaks for this young man, whose name is Andrew. What I would say is this: consider the possibility that we are living through the discipline you ask for, and that this is a chastisement.

Andrew, let me tell you something. In the Sigrid Undset novel Kristin Lavransdatter, the headstrong title character falls passionately in love with Erlend, a nobleman who is unsuitable for her, in the judgment of her pious father, Lavrans. It’s set in medieval Norway, in a time and place where fathers had to give their consent for their daughters to marry. Pious Lavrans cherishes Kristin, and does not want her to marry this inconstant man, who, he fears, will hurt and disappoint her.

Kristin resists this bitterly, and at length, withdrawing emotionally from her father. Finally, Lavrans consents to the betrothal, because he fears that denying his deeply depressed daughter the man she loves will damage her more than the marriage itself. The rest of the novel is about Kristin living with the consequences of that choice. I’m not finished with it yet, but it’s becoming clear that old Lavrans knew better than his passionate child, whom he allowed to follow her bliss into a dark wood because he loved her.

This is how it is with us and God the Father. The thing is, we expect God to deal with us directly, but that’s rarely how it happens. It is woven into the fabric of creation that He works with us through the nature of things. When fathers (and mothers) rebel against God’s will, children and children of children suffer too. Kristin’s sons carry the weight of their mother’s choices … but then again, if their mother had not married Erlend, they would not exist, would not have received the gift of life.

How do we know that this agony of faithlessness that we are suffering through now isn’t the birth pangs of something beautiful and life-giving? We don’t; that’s up to us.

It sounds like something a preacher would say, but really, I have lived it, and am struggling to live it now. My 2015 book How Dante Can Save Your Life is about how I returned to my hometown after living away for many years, only to discover that for deep and emotionally complicated reasons, my family didn’t really want us. It centered on my broken relationship with my father. I knew he loved me, but I also knew he didn’t approve of me. I had spent all my life trying and failing to earn his love.

This final rejection plunged me into a crisis that was spiritual, emotional, and physical. I became chronically ill with the Epstein-Barr virus (mononucleosis). A rheumatologist said that I had better take my wife and kids and move away, or I would never get better. I told him I couldn’t, because I needed to be here to help care for my aging parents, and besides, I couldn’t ask Julie and the kids to move yet again.

“Well, you’d better find inner peace somehow,” he said.

The story of how I did that has to do with discovering, by happy accident, Dante’s Divine Comedy. I tell the story in my own book, so I won’t belabor it here. But for the angry Evangelical reader’s sake, I will say that the solution to my crisis had a lot to do with breaking the spell of my father had inadvertently cast on me. I suffered because I had made an idol of him, and had put him in the place of God the Father. I thought I could not live without his approval, and desperately, desperately wanted it. And I had confused God the Father with my dad, assuming that He loved me but didn’t approve of me, but I could make him love me if I was able to give Him what He wanted.

Once the nature of the knot that bound was was exposed, the Holy Spirit untied it, and I began to recover. Nothing really improved between my father and me, but my heart was changed towards him — and towards God. Here’s the amazing thing: because I was able to find the strength to endure, and to love him through the pain, I was able to be present on the day a few months before he died, when, with his chin quivering and tears filling his eyes, the old man humbled himself to ask my forgiveness.

I was granted the gift of living with him in his bedroom at home on the last week of his life, as he lay dying in a hospital bed the home hospice people had given him. We had no deep conversations. I just read him stories, rubbed lotion in his feet, and prayed over him. I held his hand as he drew his last breath. It was golden, all of it.

Had I never come back to Louisiana, I would not have been shredded by the revelations of what my family really thought of me. I would not have become so ill. But I also would not have gone on that pilgrimage through the valleys and caves of my own heart, and would not have done battle with the dragons there. Maybe I would not have learned to accept the love of God. I certainly would not have been present to hear my father tell me he was sorry for how he had treated me, nor would I have been there when he gave his spirit over to God, and left me with a hard-won, durable blessing.

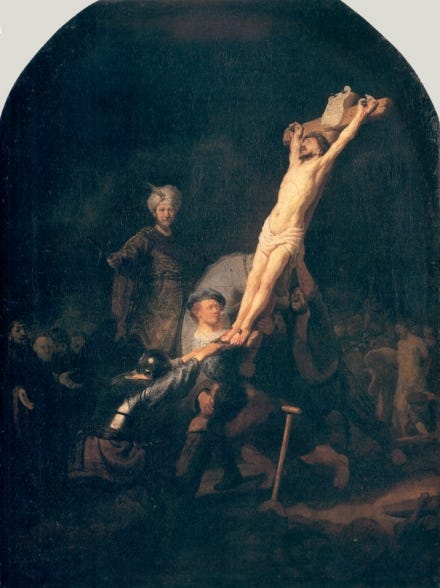

It is impossible to separate the peace from the conflict, the labor from the rest, the joy from the pain. Does it make sense to me? No, it does not. But that’s how it is with us. Why did God have to become a man and suffer and die? These are deep mysteries that we can never solve, but that we can enter, and live. You say that you want your Father to treat you like a son? You are asking for this:

And if you accept that, Andrew, you will receive this:

I can’t explain why this works the way it does. But I know it does, because I have walked through that dark wood. Believe me, Andrew, as I struggle with things now, I try so very hard to remember the things I learned there. All of life, we tread this path. My poor father, his death was slow and painful and humiliating. But at the very end, he called for the Methodist pastor, who was new in town, and whom he barely knew, because he wanted to make a confession. Methodists don’t have confession, but he wanted to tell a pastor about secret sins, and pray with her for God’s mercy. I don’t know what my father told the pastor, but I have an idea, and I am certain that it was only being reduced to skin and bones, and clad in a diaper like a baby, that broke the steely pride my father wielded like a broadsword, and drove him to ask for mercy.

It is true for me too. And you. You asked for God the Father to discipline you. Well, He is. He is asking you to find the strength to believe though the men who were supposed to keep vigil have scattered in their fear and weakness. He is breaking you to make you a man. “With his stripes we are healed,” said the Prophet Isaiah, of the scourged Christ to come. We cannot be healed unless we also share in his wounds. We cannot be resurrected unless we die with him too.

I’m writing this to you, young man, but I’m also writing it to myself. You cannot imagine how much I need to believe this, to know that it is true. That sentimental saying you see on coffee mugs at gift shops? ‘Be Kind, For Everyone You See Is Fighting A Great Battle’?

Yeah, it’s true.

I look around now, and I see little to inspire. The churches are weak. The people are faithless. I come from that world too, and I’m not innocent.

But listen, I have seen another world. When I went to Slovakia last year to report for my book Live Not By Lies, I met Christians who told me of the great deeds of previous generations. You see this worthless bench of bishops today? Well, I went to the apartment of Jan Chryzostom Korec, secretly consecrated a bishop in 1950, and given the responsibility to serve the underground church in Slovakia. He was 27 years old. That man, Bishop Korec, worked as a laborer, and spent eight years in prison. He ministered to the underground church constantly. He survived two assassination attempts. In 1990, after the fall of Communism in Czechoslovakia, Pope John Paul II made him a cardinal. I visited the tomb of Cardinal Korec in the Nitra cathedral, and fell on my knees to thank God for giving that holy bishop the courage to hold the line, and to ask Cardinal Korec to pray for me and for all of us, that we would do the same, come what may.

Nobody will remember these faithless bishops we have today. The memory of Cardinal Korec will endure until the end of time.

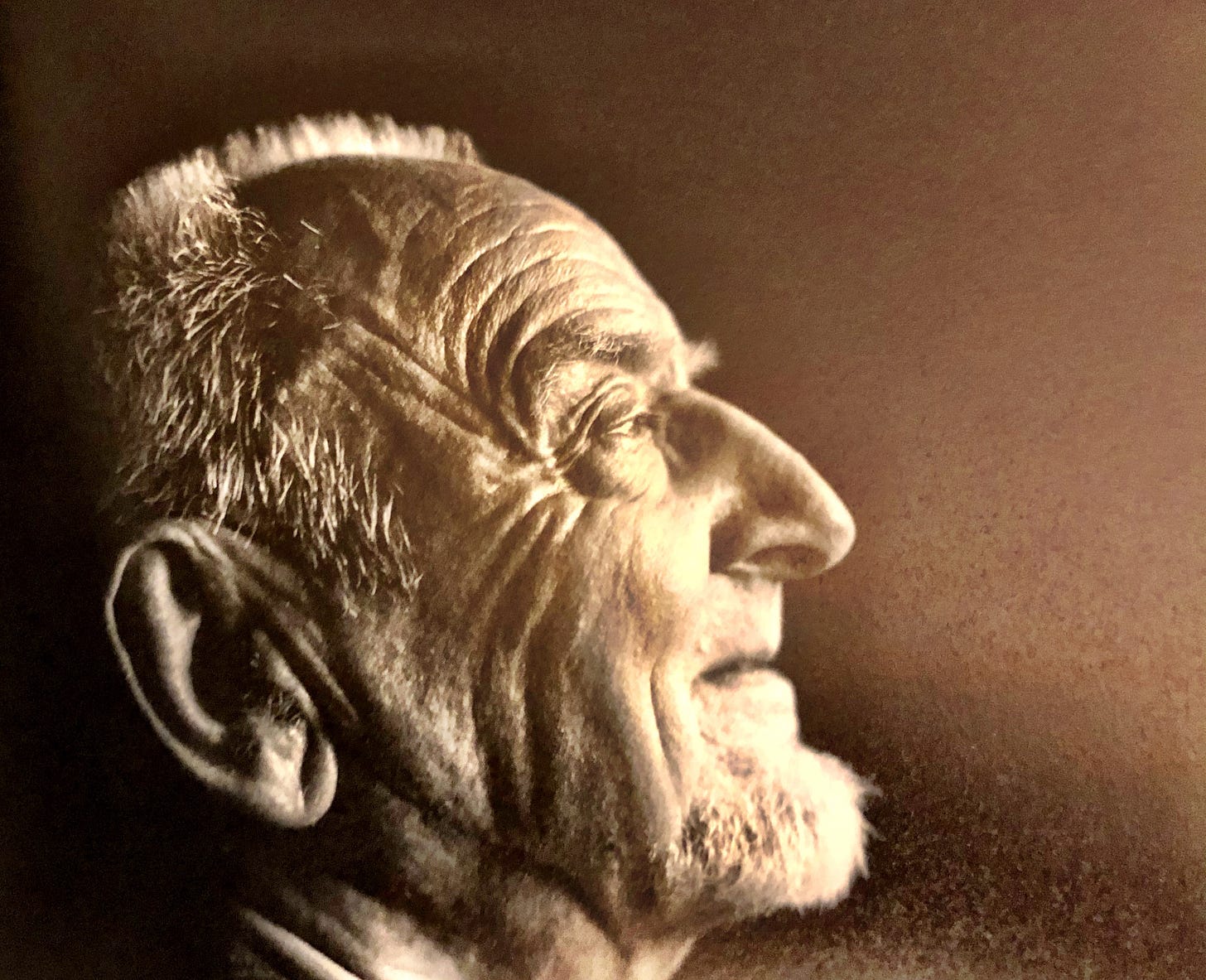

In Slovakia, I met a young photographer, Timo Križka, who was a small boy when Communism ended. Timo has been successful at his art, yet he told me that despite having liberty and comfort beyond his parents’ generation’s dreams, he was unfulfilled. Then he took up a project of visiting elderly Slovak Catholics who had been imprisoned for their faith under Communism. He interviewed them, and made their portraits. Here is one of them: Father Bernard Panči, a priest who spent four years in prison for treason for refusing to collaborate.

In Light In Darkness, a book of portraits and character sketches of these men and women, Timo wrote of Father Panči:

Father Bernard celebrated the mass in prison, too. He took raisins soaked in water and consecrated them, turning them into the Blood of Christ, the living Hope and Light for many of his cellmates. He broke off a piece of bread from the modest rations he was given each day to use as the Host.

Timo goes on, about his visit to the dying priest, living in a room attached to a Gothic cathedral:

When I tell the young caretaker who I have come to see, she tells me that some people are angry at Bernard. They say that homeless people used to come to his window and that he would throw his extra sets of clothes out to them. One set of clothes was enough for him. His clothing is still humble — one set of clothes suffices, just as one prison shirt was enough back then.

Bernard lies still on his bed. He breathes slowly and rarely moves his eyes. He is silent the whole time.

A week after my visit, Bernard Panči died.

But he lives! I believe he lives in paradise, but his memory lives on in Timo’s photography and words. Father Panči now lives in the minds of all of you reading this story. And in you, Andrew, if you are reading it.

That photo at the top of this letter? It’s of a Slovak artist named Ladislav Zaborsky (d. 2016). He was a member of Father Kolakovič’s underground Catholic organization. The state sentenced him to seven years in prison because of that, including five months of solitary confinement. Timo writes:

Being abandoned in prison, the painter heard his inner voice: “If a man thinks that God has abandoned him, it is not true. He is only hiding. The Spirit is leading the soul, even if it is blindfolded. The light comes from the soul.”

“Solitary confinement, that was like dying out, there I had no one but God. Everything was gone. I had no idea what was happening with my family, and I did not know what would happen.” But it was exactly then, he says, that he had the most “paradise-like” months. There he wrote poems on a washbasin covered with soap bubbles from the broken-out tooth of a comb. He had to learn the verses by heart, as the lines etched in soap disappeared.

Think of it! Zaborsky had to descend into the pitch blackness in order to find God. Here is one of his late paintings. It’s so simple, but if you know where it comes from — meaning the experience in prison that refined the artist — it means the world.

Think, Andrew, of the Rembrandt painting above, of the Prodigal Son. It is incomparably more accomplished artistically, but me, I see similar power in them both. Look at the hunched man in the Zaborsky painting, on his knees and clinging to the unseen but present Christ for life. There you are too. You just can’t see it yet. The Spirit is leading your soul, even if you’re blindfolded.

Ladislav Zaborsky lived, suffered, triumphed. So did Father Bernard Panči. So did so many holy men and women, whose names I had never heard, and whose lives might as well have been poems traced on a bar of soap. But their stories now bear witness to the truth — and also to the truth that God does not abandon us, no matter how much we suffer.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, writing in The Gulag Archipelago, said:

"Bless you prison, bless you for being in my life. For there, lying upon the rotting prison straw, I came to realize that the object of life is not prosperity as we are made to believe, but the maturity of the human soul."

Timo Križka learned the same thing by talking to these political prisoners in his own country. From Live Not By Lies:

From his interviews with former Christian prisoners, Križka also learned something important about himself.

He had always thought that suffering was something to be escaped. Yet he never understood why the easier and freer his professional and personal life became, his happiness did not commensurately increase. His generation was the first one since the Second World War to know liberty—so why did he feel so anxious and never satisfied?

These meetings with elderly dissidents revealed a life-giving truth to the seeker. It was the same truth it took Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn a tour through the hell of the Soviet gulag to learn.

“Accepting suffering is the beginning of our liberation,” he says. “Suffering can be the source of great strength. It gives us the power to resist. It is a gift from God that invites us to change. To start a revolution against the oppression. But for me, the oppressor was no longer the totalitarian communist regime. It’s not even the progressive liberal state. Meeting these hidden heroes started a revolution against the greatest totalitarian ruler of all: myself.”

None of these men and women I interviewed last year in Eastern Europe and Russia ever blamed God for their suffering. They did not seek it out, but they received it as an opportunity to deepen their faith, their trust in God, and learn greater compassion for the poor and the wounded. The soul resists purifying grace, because it is painful. Think, Andrew, that your own pain in the face of the weakness and corruption in the church might be the fruit of your parents’ generation choosing comfort over grace. Maybe you are being called now to restore what was lost. Maybe your pain is a sign not of your distance from God, but of your nearness.

I’ll leave you with this quote from Henri Nouwen’s great little book The Return of the Prodigal Son, a meditation on the Rembrandt painting:

For most of my life I have struggled to find God, to know God, to love God. I have tried hard to follow the guidelines of the spiritual life—pray always, work for others, read the Scriptures—and to avoid the many temptations to dissipate myself. I have failed many times but always tried again, even when I was close to despair.

Now I wonder whether I have sufficiently realized that during all this time God has been trying to find me, to know me, and to love me. The question is not “How am I to find God?” but “How am I to let myself be found by him?” The question is not “How am I to know God?” but “How am I to let myself be known by God?” And, finally, the question is not “How am I to love God?” but “How am I to let myself be loved by God?” God is looking into the distance for me, trying to find me, and longing to bring me home.”

Father Nouwen teaches that we can only come to God as the Prodigal Son — through pain, brokenness, and humility — but we must end by learning to be the good Father, with hands that busy themselves not with writing misdirections, policies, and protocols, but rather with hands that console, heal, and rebuild.

Consider, Andrew, that you are learning now how to receive those hands on your shoulders, and one day be worthy of offering them in mercy to others.