'The marvellous is indeed an aspect of the real'

On a Texas roadtrip with Robertson Davies

God loves a Bee Gee

Hello from Temple, Texas. I drove all day to get here to a private event tonight — yes, masks were worn — and have a Thursday night event in Austin. On Tuesday night I missed an issue for the first time since I’ve been doing this daily newsletter — for over a month. I didn’t feel too bad about it, because it’s still free for now. I won’t be doing that when I go paid, and if I have to, I will make it up over the weekends. I take doing this seriously, but time got away from me last night. I’ve mentioned here that it’s a lot more difficult doing blog posts that focus on deeper things, or at least things that aren’t a hot take on news of the day. At the risk of repeating myself, writing this newsletter is good training for my own inner eye — to train it to see more deeply, and to take in more light. Thanks for your patience.

Anybody who has traveled the highways of the Great State of Texas knows where I am in the photo above: at a Buc-ee’s (this one was in Katy, near Houston). They are vast travelers’ convenience stores, each about the size of Rhode Island (seriously, though, the one in New Braunfels is 67,000 square feet). They are known for their exceptionally clean bathrooms, and massive array of snack foods. Your car cannot pass Buc-ee’s without stopping. It’s just a Texas thing.

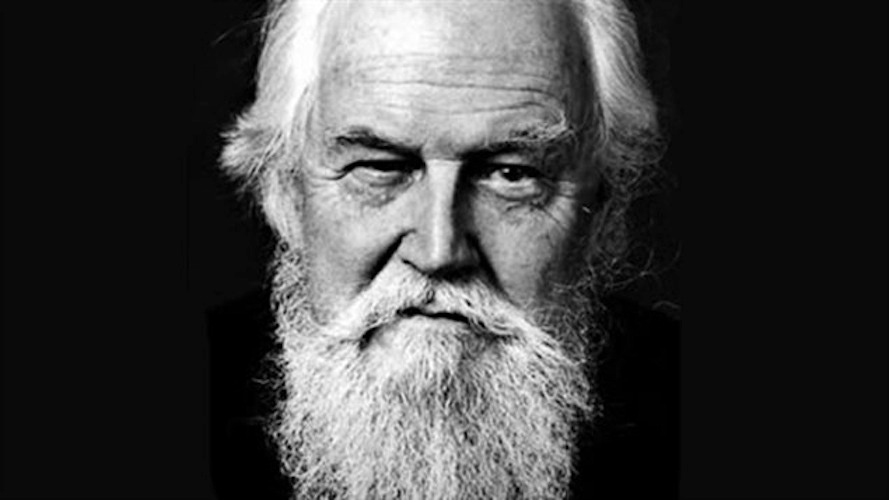

I noticed in the Buc-ee’s photo above that Your Working Boy’s unruly hair has finally gotten long enough so that gravity overcomes the cowlicks. If you look at the hair from a different angle while on your second Manhattan, and squint, you might think of Barry Gibb of the Bee Gees. Actually, you wouldn’t at all think of Barry Gibb, unless you’ve just watched the nice Bee Gees documentary that just premiered on HBO. Barry Gibb had the best head of hair of any 1970s pop star:

Feathering — ’memba that? I had a big Bee Gees poster on my bedroom wall in 1977 and 1978, their Saturday Night Fever heyday. “Stayin’ Alive” never gets old, and “How Deep Is Your Love?” remains one of the all-time slow dance classics. But their simpering 1978 love song “Too Much Heaven” reduced 11-year-old me to a quivering Jell-O mold of awe. I vowed to listen to the 45 every night at bedtime for the rest of my life. Which turned out to be a couple of weeks, I think. When I think about why everybody soured on the Bee Gees, I think of that song — the falsetto, the goopy orchestration, it was just too much. But do you want to hear it differently? Check out this a cappella version done a few years ago by the American fraternal trio Hanson. It’s actually a lovely song that was ruined by overproduction.

So I watched the HBO documentary the other night with my son Matt, who is a college radio DJ. I could tell that he found it hard to comprehend why there was such an intense backlash against the Bee Gees, and against disco in general. I tried to explain it to him, but I don’t think he was buying. And to be honest, the documentary really does give reason to reassess the Bee Gees as songwriters and performers. The Brothers Gibb really did have incredible talent. I had forgotten — or more likely, never knew, as I didn’t know who they were until the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack, and then suddenly they were the epitome of uncool — that they didn’t always have that falsetto thing going on. The documentary reveals that falsetto singing, which became the group’s trademark, was discovered in the studio with producer Arif Mardin in 1975, when Mardin told them that the song “Nights On Broadway” needed a little something extra. Here’s a live performance of the song, from 1975, in which Maurice Gibb does the falsetto part. It’s Barry in the original, but this is such a nice live recording, because it shows how tight their harmonies were.

Why did I get going on the Bee Gees? Probably because it makes me happy to think of their music, partly for nostalgic reasons, but mostly, I think, because they were really good singers, and I love to think about how it took boys who were brothers to sing such tight, instinctive harmonies. If you haven’t thought about the Bee Gees except as the band that circa 1980, you were embarrassed to have ever liked, you really should watch this movie and give them a second look. Here’s the trailer:

Robertson Davies

Normally I do a fair amount of traveling for my work, but not this year. I’m on my third long car trip of the fall for the book. I don’t feel quite safe flying yet, and besides, it’s nice just to get out on the road, and relax with an audio book. I never have that much unbroken time to give myself over to a book.

This morning I choose to use an Audible credit to download Fifth Business, the first novel in the late Canadian writer Robertson Davies’s Deptford Trilogy, which appeared from 1970-75. I first discovered these novels in the winter of 1993-94, living mostly alone in a friend’s big, chilly country home. I stumbled into Fifth Business just before Christmas, and read them all straight through, finishing the last one on a train from Oslo to Lillehammer, in Norway. Synchronicities were popping all over — appropriately enough, because the second novel in the trio, The Manticore, is about Jungian analysis. The final book, World Of Wonders, centers on a character named Magnus Eisengrim. I finished it shortly before the train pulled into snowy Lillehammer. I was exhausted, having stayed up late the night before, and recovering from the flu. I trudged through the snow to my hotel, checked in, got my key card, and slogged to the room. When I approached the door, I saw a plaque affixed to it at eye level. It read: MAGNUS.

I froze. It turned out that each room in this little hotel was named for a Norse king. I was in King Magnus’s chamber. I entered, dropped my bags, and fell into bed to sleep, without even pulling the covers back. And there I dreamed. For the next three nights — in Lillehammer and Trondheim — I had powerfully symbolic dreams about my life.

Some back story: Months earlier, I had aborted my own launch into the world by returning from Washington DC to my hometown in south Louisiana after my sister had her first child. I felt desperately far from my family, and wanted to be with them again. I quit my good Washington journalism job to move back and be with them, with no particular plans. I just wanted to be part of their lives. After a couple of months, and a revealing conversation with my father — the night of December 7, 1993 — it had become jarringly clear that I could not stay there, that if I did, my domineering father would crush my spirit. I was lost, filled with regret and self-reproach — so much so that I could not sleep that night. I got out of bed at two a.m., got dressed, and drove 40 miles into Baton Rouge, and sat till near daylight at Louie’s Cafe near LSU, drinking coffee and worrying.

When the sun came up the next morning, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception (!), I found myself alone, except for an old Irish priest moving in the shadows, in a Catholic church downtown. I knelt in front of a statue of the Virgin, begging her to pray for me to get out of Louisiana. “I’ve seen what I needed to see,” I said. “Please, help me.”

A couple of weeks later, I pulled Fifth Business off the shelf at my friend’s house one afternoon, and was instantly hooked. It’s the written recollection of Dunstan Ramsay, a recently retired Canadian school teacher who writes to the headmaster of his school in pique over the student newspaper’s callow article about the end of his career. Ramsay has a story to tell about the mystical adventure of his life, beginning when he was 10 years old in the rural Ontario town of Deptford. His childhood chum, a rich kid named Percy Boyd Staunton, throws a snowball at Ramsay, who dodges it. The snowball hits Mary Dempster, the pregnant young wife of the town’s Baptist minister, who is walking with her. Buried within the snowball is a stone. When it strikes Mrs. Dempster, she collapses to the ground. She delivers her child prematurely, and is left mad by the whole experience.

One unintentionally violent moment unites the lives of Ramsay, Staunton, and Paul Dempster, the unfortunate woman’s son. The rigidly Protestant villagers don’t know what to make of Mrs. Dempster, suddenly simple-minded, who wanders the town handing out gifts. The poor woman’s grotesque and scandalous tryst with a stranger destroys her and her family’s reputation. Only Ramsay sees something sacred in the fallen woman, who performs a bona fide miracle (that no one will believe, other than Ramsay, who witnessed it). Miracles don’t happen, the villagers insist, and if they did, they wouldn’t happen through the prayers of a disgusting madwoman. As Ramsay writes, “the Presbyterianism of my childhood effectively insulated me against any enthusiastic abandonment to faith.”

But young Ramsay knows what he saw. Later, lost under fire in Passchendaele, in some of the worst fighting of World War I, Sgt. Ramsay lay badly wounded in the ruins of a church, when he spies the statue of Mary, as the Immaculate Conception. She has the face of Mrs. Dempster. Ramsay wakes up many months later in a hospital back in England. He had been left for dead, but was later discovered, and miraculously survived.

He doesn’t become a fervent Christian, but Ramsay does come to believe that religion tells us something true about reality. For him, “religion was much nearer in spirit to the Arabian Nights than it was to anything encouraged by St. James’ Presbyterian Church.” Back home in Canada, he goes to university, and becomes a scholar of the lives of the saints. His academic pursuits take him to Europe in search of obscure stories and apocrypha of holy men and women all but lost to history. In thinking especially of Mary Dempster, an example of the kind of saint the Russian Orthodox call a yurodivy, or “holy fool,” Ramsay comes to realize that grace is not bounded by logic and rules, but by the mysteries of love. Ramsay ponders:

"Why do people all over the world, and at all times, want marvels that defy all veritable facts? And are the marvels brought into being by their desire, or is their desire an assurance rising from some deep knowledge, not to be directly experienced and questioned, that the marvellous is indeed an aspect of the real?"

Well, I won’t tell you any more. Let me tell you, though, that reading the rest of this novel, and its two sequels, while on that journey, and then having a number of cracking synchronicities, and intensely symbolic dreams — it was overwhelming, like nothing that had ever happened to me. I was reeling by the time I got to my hotel in Bergen, and immediately wrote, on hotel stationery, to Michael Rust, a Catholic friend in Washington who knew something about Jungian dream interpretation. I told him of the synchronicities, and of the dreams. (I won’t bore you with the details here; there is little more boring than people telling you about their dreams.) I asked him to reply to me in a letter addressed to Louisiana, for I would be home in ten days or so.

When I arrived back in Louisiana, there was a letter from Michael. He told me the dreams were about how as a child, I felt menaced by my father’s domineering nature, and took refuge in books. Discovering the Christian faith brought me back into the world. I was now being called to leave my family and plunge into the life God had for me, but my family would not understand it; nevertheless, I had to go.

There was something else for me in the pile of mail: a job offer from the Washington Times, my old paper. It was my ticket out — if I wanted it. I should have accepted the job immediately, but me being young and immature, I wanted a Sign. I had three weeks to think about it. I prayed the rosary for a sign, but nothing came. Finally, at the last minute, I phoned DC and accepted the job. I went into a bedroom at the country house, shut the door, and prepared to say a rosary of thanksgiving for the Virgin’s prayers on my behalf. As I prayed, the room filled with sunlight and the strong aroma of roses. The sunlight and roses lasted only for one decade of the rosary, but it was enough. I searched everything in the room afterward, but there was nothing that could have made that aroma. It was the dead of winter.

When I began praying that rosary, I had also asked the Virgin silently to “hold the hand” of a friend visiting me that weekend in the country house. My friend was going through a bad divorce, and was not a woman of faith. After my prayer and the experience of roses, my friend, who had been walking in the field next to the house as I prayed, came into the house. With wide eyes, she proffered her right hand, asking me to smell it. It smelled of roses.

She had not put perfume on it. She had not washed it with floral soap. She said she moved it to her nose when she walked in from outside, and suddenly there are roses on her hand. I told her what I had just prayed. Her jaw dropped. The aroma disappeared.

Two weeks later, I moved back to Washington, and resumed my life with confidence.

I re-read the Davies novels not long after I married, so I guess it’s been about twenty years since I’ve been in this world. How different it all looks now. I love it still, and I love too how this book is reminding me to be patient, to keep watching, and waiting on grace. The marvelous truly is an aspect of the real. Anything might happen.

This is both a threat and a promise.

Fifth Business is in part about how the shadow is inextricably attached to the light — and how good things can come to us through bad or broken people. I can testify to that in a pretty striking way. In 2007, in the Dallas Morning News, I wrote the story about my own engagement, and how it took place in connection with a holy fraud carried out by a wicked monk. I will leave you with that column:

On a scrubby hilltop in the middle of nowhere, amid a squalid trailer park masquerading as a monastery, the life of Samuel Greene – known to his followers as Father Benedict – came this month to an abrupt conclusion.

Suicide? Could be, says the sheriff. Sam Greene was a convicted pedophile, a purported pothead, an audacious blasphemer, a morbidly obese slob and a thoroughgoing fraud. He was, quite simply, a wretch.

And yet I owe to his life more than I can say.

In 1981, Mr. Greene, a TV real-estate pitchman, declared himself an Eastern Orthodox monk and founded Christ of the Hills monastery – mostly mobile homes near a wooden chapel – in the countryside outside the [Texas] Hill Country town of Blanco.

Four years later, Father Benedict, as he now called himself, acquired an icon of the Virgin Mary. He and his followers soon claimed the icon was miraculously "weeping" myrrh. Word spread, and soon the multitudes were making their way to the isolated monastery to venerate the icon and pray for miracles of their own.

I was one of them. In the early 1990s, an Austin friend who shared my newfound Catholic faith and interest in mysticism took me to see the icon. Every time I'd go visit him, we'd make a pilgrimage to Blanco. By the middle of the decade, having wearied of the single life, I asked God for a wife. I prayed the rosary fervently for this intention, petitioning the Virgin for her help. In Blanco, I would pray likewise before the weeping Mother of God.

I didn't worry much about the icon's validity. Why would monks lie? But I was young and naive in my faith then, credulous and childishly enthusiastic about signs and wonders.

In the autumn of 1996, I flew from my home in Florida to Austin to meet Frederica Mathewes-Green, an Orthodox writer friend in town for a conference. We would go to Blanco together. At Frederica's bookstore presentation, I met a University of Texas journalism student. I was instantly thunderstruck and, before parting, invited her to go with us to see the weeping icon the next day. The student accepted, and the next morning, I once again stood before the miraculous image, praying silently that if this girl was The One, I would know it in my heart.

Four months and many flights to Austin later, I made my final visit to the Blanco monastery. Inside the chapel, I asked that student to marry me. She said yes. My prayers were answered. Nearly 11 years and three children later, I remain the most blessed of men.

My wife and I hadn't been married long before the Blanco monastic community began to collapse. In 1999, the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia severed ties with the monks after allegations of sexual abuse there. Father Benedict pleaded guilty to indecency with a child and received probation. Another monk was convicted and sent to prison.

By then, I figured the icon was fake. Did I feel a fool for believing in it? Sure. But I had faith that my prayers, sincerely offered, had been heard and that heaven had said yes. That was enough, though I winced at the stain on that cherished courtship memory.

Subsequent arrests revealed that the monastery was, in fact, a snake pit. Last year, in secretly taped conversations, Mr. Greene admitted he'd been molesting kids since the 1970s, smoking dope, engaging in reported "deviant sexual contact" and otherwise violating terms of his probation. He also confessed that he'd faked the icon.

Because of all this, Father Benedict faced the prospect of prison. Whether by fate or by his own hand, Sam Greene's last con was cheating justice. In this life, anyway.

I am glad it is not given to me to judge him. By one standard, Father Benedict deserves a millstone lashed to his neck for eternity. That's what I'd have given the old buzzard, but God's a better Christian than I am. And yet, I'm forced to admit that from Sam Greene's wicked deeds, my beloved family sprung. I can't help wondering: no fake icon, no visit to Austin, no meeting my true love.

This mystery throws everything off balance. It offends my sense of order and righteousness to recognize it, but the mere existence of my children is evidence that however miserable and mean and degraded, that dirty old monk, probably in spite of himself, was once an instrument of grace.

Did other good fruit emerge from this poisoned vineyard? Who knows, and who can say whether it counts for anything? But when Sam Greene is judged, there my little family stands, however reluctantly, as silent witnesses for the defense, pleading on his behalf for the same thing every one of us will one day need: mercy.

P.S.

I eagerly await your e-mails. I read them all, though I regret that I don’t have time to answer them. Write me at roddreher — at — substack — dot — com. Unless you say otherwise, I will consider all letters to be bloggable, though I will not use names or identifying details unless you ask me to.