The Theological Mystery Of Camp Mystic

Where Was God In The Flood That Swept Away Little Girls?

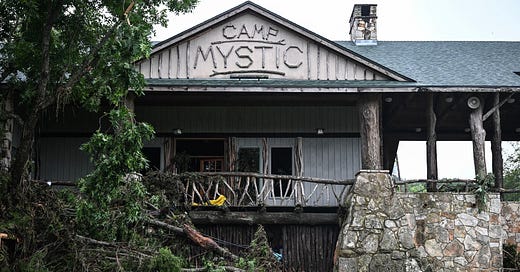

I can scarcely wrap my head around the magnitude of a camp full of little Christian girls being swept away by a raging flash flood. But that is what happened in the Texas Hill Country over the weekend. Here are just a few of the dead:

A week ago, these little girls and their families were so happy. And now they’re gone, swept away in a night of horror.

Watch this 2020 promotional video for the camp. It looks like a place of joy:

I don’t doubt the existence of God, not even a little bit. But if I did, this kind of thing would be the reason why.

In 1755, on All Saints Day, a terrible earthquake and tsunami devastated the city of Lisbon. Up to 60,000 people died. Voltaire, the great French atheist, responded a year later with this poem demanding to know how an all-good and all-powerful God could permit it. Excerpt:

Unhappy mortals! Dark and mourning earth!

Affrighted gathering of human kind!

Eternal lingering of useless pain!

Come, ye philosophers, who cry, "All's well,"

And contemplate this ruin of a world.

Behold these shreds and cinders of your race,

This child and mother heaped in common wreck,

These scattered limbs beneath the marble shafts--

A hundred thousand whom the earth devours,

Who, torn and bloody, palpitating yet,

Entombed beneath their hospitable roofs,

In racking torment end their stricken lives.

To those expiring murmurs of distress,

To that appalling spectacle of woe,

Will ye reply: "You do but illustrate

The iron laws that chain the will of God"?

Say ye, o'er that yet quivering mass of flesh:

"God is avenged: the wage of sin is death"?

What crime, what sin, had those young hearts conceived

That lie, bleeding and torn, on mother's breast?

Think of the little girls’ bodies, their “scattered limbs” tangled in the flood-harried trees. This is the most powerful argument against the existence of God, at least to my mind. Voltaire is right to say that people who wish to claim “everything happens for a reason” really should shut up. What good does that bloodless claim do for a mourning mother and father in Texas this morning?

But the theologian David Bentley Hart has an answer for them. He published an essay in First Things in 2005, confronting the abyss of pain caused by the South Asian tsunami. Excerpts:

Not that one should be cavalier in the face of misery on so gigantic a scale, or should dismiss the spiritual perplexity it occasions. But, at least for those of us who are Christians, it is prudent to prepare ourselves as quickly and decorously as we may for the mixed choir of secular moralists whose clamor will soon—inevitably—swell about our ears, gravely informing us that here at last our faith must surely founder upon the rocks of empirical horrors too vast to be reconciled with any system of belief in a God of justice or mercy. It is of course somewhat petty to care overly much about captious atheists at such a time, but it is difficult not to be annoyed when a zealous skeptic, eager to be the first to deliver God His long overdue coup de grâce, begins confidently to speak as if believers have never until this moment considered the problem of evil or confronted despair or suffering or death. Perhaps we did not notice the Black Death, the Great War, the Holocaust, or every instance of famine, pestilence, flood, fire, or earthquake in the whole of the human past; perhaps every Christian who has ever had to bury a child has somehow remained insensible to the depth of his own bereavement.

As annoying as atheists shouting, “See! See!” are, to Hart

…more troubling are the attempts of some Christians to rationalize this catastrophe in ways that, however inadvertently, make that argument all at once seem profound. And these attempts can span almost the entire spectrum of religious sensibility: they can be cold with Stoical austerity, moist with lachrymose piety, wanly roseate with sickly metaphysical optimism.

Mildly instructive to me were some remarks sent to Christian websites discussing a Wall Street Journal column of mine from the Friday following the earthquake. A stern if somewhat excitable Calvinist, intoxicated with God’s sovereignty, asserted that in the—let us grant this chimera a moment’s life—“Augustinian-Thomistic-Calvinist tradition,” and particularly in Reformed thought, suffering and death possess “epistemic significance” insofar as they manifest divine attributes that “might not otherwise be displayed.” A scholar whose work I admire contributed an eloquent expostulation invoking the Holy Innocents, praising our glorious privilege (not shared by the angels) of bearing scars like those of Christ, and advancing the venerable homiletic conceit that our salvation from sin will result in a greater good than could have evolved from an innocence untouched by death. A man manifestly intelligent and devout, but with a knack for making providence sound like karma, argued that all are guilty through original sin but some more than others, that our “sense of justice” requires us to believe that “punishments and rewards [are] distributed according to our just desserts,” that God is the “balancer of accounts,” and that we must suppose that the suffering of these innocents will bear “spiritual fruit for themselves and for all mankind.”

For Hart, Voltaire’s indictment of Christian belief is shallow, because it protests against the Deist idea of a watchmaker God who designed the universe just so. Far more serious, Hart says, is Ivan Karamazov’s case against God. Dostoevsky’s atheist character rejects the idea of salvation itself, on grounds that anything at all that could justify the suffering of the innocent is repulsive.

Voltaire sees only the terrible truth that the actual history of suffering and death is not morally intelligible. Dostoevsky sees—and this bespeaks both his moral genius and his Christian view of reality—that it would be far more terrible if it were.

And:

There is, of course, some comfort to be derived from the thought that everything that occurs at the level of what Aquinas calls secondary causality—in nature or history—is governed not only by a transcendent providence, but by a universal teleology that makes every instance of pain and loss an indispensable moment in a grand scheme whose ultimate synthesis will justify all things. But consider the price at which that comfort is purchased: it requires us to believe in and love a God whose good ends will be realized not only in spite of—but entirely by way of—every cruelty, every fortuitous misery, every catastrophe, every betrayal, every sin the world has ever known; it requires us to believe in the eternal spiritual necessity of a child dying an agonizing death from diphtheria, of a young mother ravaged by cancer, of tens of thousands of Asians swallowed in an instant by the sea, of millions murdered in death camps and gulags and forced famines. It seems a strange thing to find peace in a universe rendered morally intelligible at the cost of a God rendered morally loathsome.

He goes on:

I do not believe we Christians are obliged—or even allowed—to look upon the devastation visited upon the coasts of the Indian Ocean and to console ourselves with vacuous cant about the mysterious course taken by God’s goodness in this world, or to assure others that some ultimate meaning or purpose resides in so much misery. Ours is, after all, a religion of salvation; our faith is in a God who has come to rescue His creation from the absurdity of sin and the emptiness of death, and so we are permitted to hate these things with a perfect hatred. For while Christ takes the suffering of his creatures up into his own, it is not because he or they had need of suffering, but because he would not abandon his creatures to the grave. And while we know that the victory over evil and death has been won, we know also that it is a victory yet to come, and that creation therefore, as Paul says, groans in expectation of the glory that will one day be revealed. Until then, the world remains a place of struggle between light and darkness, truth and falsehood, life and death; and, in such a world, our portion is charity.

As for comfort, when we seek it, I can imagine none greater than the happy knowledge that when I see the death of a child I do not see the face of God, but the face of His enemy. It is not a faith that would necessarily satisfy Ivan Karamazov, but neither is it one that his arguments can defeat: for it has set us free from optimism, and taught us hope instead.

Hart later expanded this essay into a book-length treatment of the theme.

This is the same hope that sustained the Christian prisoners languishing in communist gulags. It was not the idea that they did something to deserve their suffering, according to some sort of metaphysical moral calculus. Rather, it was the idea that God has not forgotten them, that He too mourns their pain. The same God that entered into human history as a flesh-and-blood man, who bore the hatred of the world, and who died the most wretched and painful of deaths, willingly. When Jesus rose from the dead, he did not emerge from the grave with a brilliant argument that explained everything that happened to him. He arose having defeated death. His resurrected body — not the ghostly appearance of a body, but His actual pierced and whipped flesh — is the evidence we need to know that in the end, death will not triumph.

Those sweet little Texas children yet live. That is our hope. That is our only hope. It is futile to understand why God permitted it to happen. Even Jesus himself, on the cross, quoted the Psalmist saying, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” He knew the desolation that the families of the dead on the Guadalupe River know. There is no syllogism that can take that pain away. There is only enduring it. And the only thing that makes it endurable is the faith that death will not win, that death has not won. We abide in that hope, because there is nothing else to be done.

My sister wasted away from cancer, and died in her husband’s arms, choking in her own blood, after the tumor severed an artery in her lungs. The horror of that scene was so intense that their neighbor, the first to walk in and see her husband with her body on the living room floor, could not bring himself to describe it to me when I asked him. Mr. Ronnie was the first to see a woman he had watched grow up from a baby girl into a wife and mother of three beautiful daughters, lying wretchedly in a puddle of the blood that drowned her, as her husband, whom she had loved since junior high school, held her, powerless to save her from the sanguinary tide flooding her lungs.

How do you justify that? And yet, I can tell you this: the very day she was diagnosed with the cancer that set in motion the events leading up to that dread day in September 2011, I slept in her bed, keeping her youngest daughter company while her mother and father were in the hospital, and after the child’s heavy breathing gave me permission to let go, I wept over the injustice of what had happened to Ruthie. As I lay there silently demanding of God that He explain Himself, I suddenly became aware of an unseen presence hovering over me. Whatever it was — an angel, I figure — it communicated to me that I should be at peace, that what was about to happen must happen. The presence did not explain why. The message, as I understood it, was: Don’t give in to despair. All will be well.

I told my wife about this event the next morning. After that, we knew that Ruthie would suffer and die. This thought we kept to ourselves, obviously, so as not to discourage Ruthie or her family. But from that point on, we knew that the awful moment that arrived nineteen months later, after Ruthie and Mike had dropped their children off at school, was inevitable.

As you know if you read The Little Way Of Ruthie Leming, neither Ruthie nor her husband ever once considered the possibility that she would die. Indeed, on the night before she passed, she confided to her best friend that it might be time for her and Mike to talk about death. Ruthie by then was nothing but skin and bones, trailing an oxygen tank. Her friend was shocked that she had lived with Stage Four cancer for all that time, and they had not been able to consider even once that death might take her.

In the book, I excused this. Who am I to judge how a woman facing a terrible death copes with it? Later, I would come to despise it, once I saw how unprepared she and Mike had left their children for the shock of their mother’s death. This unwillingness to face the fact that life, ultimately, is tragic, became the undoing of my family. The way my family thought about things was to believe that if you lived righteously, and followed the family code, then bad things would not come to you. I didn’t appreciate the full measure of that delusion until later, after I moved there, and that way of thinking wreaked further destruction.

And yet, as the book’s narrative makes clear, Ruthie did not stagger through her sickness as some sort of happy-clappy zombie, pretending it wasn’t real. What she did was to love through it. Here’s a scene on her front porch, the day after she came home from the hospital after her diagnosis. In it, I am telling her goodbye before flying back to Philadelphia. I brought up how furious I was that her family doctor did not take seriously enough her chronic coughing, and what it might signify (Ruthie had never smoked, so lung cancer never struck him as a possibility). Had he done so, they might have caught the cancer earlier. From the book:

"Don't be mad at the doctor, Rod," she said, gripping my forearm. "I don't want any of you to be. He couldn’t have found this cancer. Not even the specialists saw it five weeks ago. But oh, I am being taken such good care of now."

She then spoke with astonishment and gratitude about the compassion shown her by Tim, by Dr. Miletello, by the Lady of the Lake nurses and staff. "They treat 200 patients in that radiation unit every day,” she said. “Two hundred! Can you believe? And they still find it in themselves to be so kind to me. It's amazing."

Ruthie and I talked about the parade of visitors who had flocked to her living room since her diagnosis. I felt protective of her, and eager to help her rest, and to spend time with her children before the radiation and the chemo took over her life. But she insisted on seeing everyone, if not for her sake, then for theirs. No matter what I said to encourage her to take it easy, she would not budge on this.

Where did she find the patience? On the way back from New Orleans the day before, Hannah and I agreed that neither of us could be teachers because we both lack the patience her mother had. Ruthie’s determination to see the good in everyone, and not to push back or get mad, had long been a source of befuddlement and annoyance to some of us who loved her. We thought at times she let people take advantage of her because she was unwilling to provoke conflict. Mam and Paw and I talked about this often, even before Ruthie got sick.

"Her class this year is really tough,” Mam told me just that morning. “The other teachers said to her once, 'How do you put up with them?' She told them, 'I love those kids, and maybe they can change.’”

It was that simple with Ruthie. But for many of us, that's the hardest thing in the world. I find it hard to love anybody that's not lovable. Ruthie found everyone lovable, if not necessarily likeable. I never thought about where this instinct comes from in her until that awful week, when I saw this habit of Ruthie's heart in the light of mortality – hers, ours -- and in the light of the spectacular generosity from all those she's touched over her lifetime. By the time I made it to Ruthie’s front porch that Saturday morning, I saw my country-mouse sister in a new way. I thought, What kind of person have we been living with all these years?

Ruthie and I talked for a while longer about the outpouring of support for her, Mike and the kids. She told me she expected to beat cancer, but it made her happy to hear about people choosing to change their lives because of her story.

“We just don't know what God's going to do with this,” she said, matter-of-factly.

Mike drove home from the pharmacy, and joined us on the porch. He said while he was in town, he'd run into a friend, who was upset over the news of Ruthie's cancer.

"He said, 'I have never in my life prayed, but when I heard this news, I prayed twice, dammit."

Ruthie slapped me on the shoulder. "See?"

As I’ve said, I think she confronted her mortality imperfectly. But she got the big things right. She never wasted a moment asking God why He allowed this to happen to her. She moved through the valley of the shadow of death with the instinct that she should try her best to bring good out of it, and to trust that by cooperating with the will of the God who is Love Itself, that the death that might overtake her one day through this disease would not have the final word.

One of the fruits of her humble way of coping with this death sentence was a bestselling book about it, Little Way. So many people over the years have told me what a difference Ruthie’s story made in their lives. It helped many cope with suffering. It helped others find their way back home.

As you who have read me for years know, especially if you read How Dante Can Save Your Life, the unlovely part of Ruthie’s legacy, and the legacy of my folks, had to do with their unwillingness to accept me and my family, because we were City People in their minds. This set into motion a series of events that destroyed my marriage and my own little family. I’m sorry to confess that I still struggle with bitterness over all this. Despite this, reading Dante helped me to face my own sins, in ways that led to repentance and partial healing of my soul and even my body (my chronic Epstein-Barr was triggered by extreme stress, according to the rheumatologist). And the story of Dante Alighieri, the Tuscan poet who was once on top of the world, until he lost everything in an instant, through no fault of his own, also helped me. If Dante had not been forced to suffer, and suffer intensely, because of all too human cruelty and injustice, he never would have written the Commedia, one of the greatest works of literature in the history of man.

I’m sure Dante would have traded the Commedia to have his family back, and to have been able to resume his life in his beloved Florence. But that wasn’t given to him. He worked with what he had, and transformed his suffering into a work of art. And not just art: as Dante told his patron in a letter, he wrote the poem not for art’s sake, but because he wanted to help his readers conquer their own confusion and despair, and find their way to God. Well, it worked for me.

Does the Commedia justify the pain of that man, Dante Alighieri, separated from his wife and his home, and forced to wander the earth, dependent on the charity of others, for the rest of his days? That’s not a question anybody can answer, and not really a question worth asking. Does all the good that resulted from Ruthie’s suffering, and the story that emerged from it, justify what happened to her? Again, a pointless question. I cannot imagine any good that might have come from that making sense of her horrible death, swept away by a tsunami of blood surging through her exhausted lungs.

But good did come of it, somehow. Her suffering and death was not pointless, because she met it with a patient heart, and a determination to love her way through it, and in particular to reach out in her own suffering to others who were suffering. Her chemotherapy ward nurses told me after her passing that when Ruthie would come for her sessions, she would make a point of introducing herself to new patients, and talk to them, consoling them and trying to give them hope and courage.

This is the way. This is the only way that makes sense, the only way to keep suffering and death from having the final word. Because He rose from the dead, He made everything new. That is our hope, as Christians. It’s a hope I cling to, and try, in my weak way, to live into as I try to put my own life together through radical suffering and brokenness.

This morning, before dawn, I said goodbye to a young houseguest who had been staying at my place for the past nine days. Lovely young man, 24, from Quebec, and a new Christian (he was baptized a Catholic this past Easter). One night during his visit, we were walking back from having wine, and we talked about marriage, which he hopes for one day.

I told him about my own experience, and the experiences of other middle-aged friends of mine. I told him how we were all young Christians like him at one point, and we all thought that the divorces that were so common in this world would never touch us. We believed in God, and we lived as righteously as we could. Our marriages, we thought, would be built on a firm foundation of piety and obedience to the Church’s teaching.

Mine failed. So did those of others I know. Still others are trapped in a maelstrom of suffering, inside broken marriages that exist in name only.

“You’re really discouraging me,” he said.

“Then you’re not hearing me correctly,” I answered. “I’m only telling you not to be unduly optimistic. The things that destroyed my marriage, I had no control over, and I couldn’t have planned for them. Things happen in life. Maybe they won’t happen to you, and I hope they don’t. But you shouldn’t go into marriage thinking that all will inevitably be well, because you are both Christians who are determined to live righteously. That is an illusion that you can’t afford.”

I wish I hadn’t put it so bluntly, because maybe young people need that illusion to get over their natural fear of making a commitment that could bring them disaster. I tried to backtrack, and say that in no way should he think that I was warning against marriage. What I am warning against, I said, is a false faith that lets you think that because you have the best of intentions, and the stoutest faith, that suffering won’t come to you. It finds us all. I told him that I look back on my own confident faith, which I was discovering when I was around his age, and wince when I think about how judgmental I was of others, especially those Christians who did not share my unwarranted confidence that I had found the formula to build a solid and resilient life that included marriage and family.

Now? I have been forced by unhappy circumstance to learn mercy. It’s all summed up in Auden’s great poem, “As I Walked Out One Evening,” about the way the passage of time plays havoc with youthful romantic certainty. Auden concludes:

‘O look, look in the mirror,

O look in your distress:

Life remains a blessing

Although you cannot bless.‘O stand, stand at the window

As the tears scald and start;

You shall love your crooked neighbour

With your crooked heart.’

There is nothing to be gained from speculating about why God allowed the wall of water to sweep those children away. There is no satisfactory answer. Is anyone made better off by concluding that God does not exist, and that suffering is ultimately meaningless?

About meaning: telling those grieving families that God Must Have A Reason only intensifies their pain. If an angel of the Lord showed up at their front door with a parchment explaining why their daughters had to drown in the darkness to achieve a higher purpose, would that somehow make it okay — even if it were true?

It is better to imagine that the suffering of those little girls on that hellish night, and the pain that their families will bear for the rest of their lives, can be redeemed by joining it to the pain of the Saviour who shared their suffering. If the witnesses to the Resurrection had all decided to keep the good news to themselves, and not to tell a soul, then Jesus would have suffered and died in vain. But they did not. They proclaimed the good news: that Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life.

This good news changed the world. These days, to prepare for my next book, I am reading and re-reading books of history, talking about how the Christian revolution turned the Greco-Roman world upside down. Because those little Texas girls were Christians, and came from Christian families, I anticipate that we will see the Holy Spirit move profoundly and publicly in the lives of those grief-stricken mothers and fathers who, despite their shock and pain, know that their Redeemer, and the Redeemer of their dead children, lives. Because He lives, so do their lost children, in eternity, where they will all be reunited one day.

In the meantime, let us love our broken neighbors, with our broken hearts. What else is there? Rage will not reverse the flow of time, or of the Guadalupe River. Despair only ensures the victory of death. There is another Way.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rod Dreher's Diary to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.