The Urgency Of 'Living In Wonder'

Embracing 'Enchanted' Christianity As A Matter Of Spiritual Survival

I’m still thinking about this great podcast interview I did yesterday with a pair of Swedish guy, both conservatives, which means they’re more or less unicorns in Sweden. One was culturally Christian, but seeking; the other is a former Christian, but still, it seemed open. We were supposed to go for ninety minutes, but we went for two hours, and could have gone for two more. This was exactly the kind of conversation I hope that Living In Wonder sparks.

The thing is, we weren’t even supposed to talk about the book, which of course neither had read. We were supposed to talk about wokeness, politics, and the kind of stuff that’s in Live Not By Lies, The Benedict Option, and my journalism of late. But our general conversation about culture and the decline of the West kept going back to themes in Living In Wonder, until finally they seemed to want to talk about that. After we stopped recording, one of them told me that I had surprised them by giving them a lot to think about, especially in the kind of programming they want to do.

This sincerely delighted me, mostly because it confirmed to me that the whole question of re-enchantment really is at the heart of our crisis. Not politics, not economics, and not religion as we normally talk about it. What my book is really about is the urgent need to re-connect in a visceral way with the Christian faith in a radical way. And by “radical,” I don’t mean anything political, or even theological. I mean experiential. Of course I am both Orthodox and orthodox, which I mean by the small-o word to mean someone located in what Hans Boersma calls “The Great Tradition” of Christianity.

Hans is a friend, and an Anglican theologian who teaches at the conservative Anglo-Catholic seminary Nashotah House. In this interview, he expands on what he means by “the Great Tradition,” which is to say, pre-modern Christianity. Excerpts:

1. You embody a desire to retrieve the “sacramental ontology” of the pre-modern tradition. What do you mean by “sacramental ontology.”

In the modern period, we tend to define the world around us by what we observe, which is to say, empirically. Often, we do not go beyond the world of the senses. But the premodern world saw this-worldly, material things (the objects that we perceive empirically) as related, or linked to greater, other-worldly, spiritual realities. Everything that we observe, for a premodern mind, was connected sacramentally to the eternal Logos or Word of God, in which they all cohere. If this is the correct perspective (which I think it is), then everything we observe with the senses is like a small-s sacrament, in which the Logos makes himself present in some way. This presence of the Word of God in creation is a real presence, not just an imaginary presence. So, the presence of God in the world is sacramental. A view of the world (an ontology) that assumes this participatory or real link between heaven and earth is sacramental—hence the phrase “sacramental ontology.”

2. How does the language of “participation” help us grasp the nature of what it means to be a Christian?

I already dropped the word “participation.” This language affirms that things of this world have their being or existence not of themselves but by participating in the eternal Word of God. This claim is important for our everyday lives, for it means that we affirm that the created world is sacred, and that we should treat it as sacred—as sharing, in some way, in the being of God. What is more, our role as human beings involves serving as priests for all of creation. We should guide the world around us—including other human beings—to participate more deeply in the life of God. So, participation language allows us to define our calling or role in the world more clearly. Our calling is always to “lift up” or “hierarchize” (as Dionysius once put it) the cosmos into the life of God.

3. Why should Christians be concerned with metaphysics?

Everyone does metaphysics. The question is not, Should we do metaphysics? But, What kind of metaphysics should we embrace? We live in a modern, anti-metaphysical age, which tells itself the story that we can get on with life without doing metaphysics. But this is a deeply problematic, deceptive stance. The reality is that, awares or unawares, we all assume a particular kind of metaphysic. People that object to Christian Platonism, saying they don’t believe in metaphysics, typically operate with a modern, anti-realist metaphysic, in which separate, atomized, material objects are they only things they will acknowledge as real. That kind of metaphysic is really quite reductive. So, in discussion, I always try to push people to acknowledge their hidden assumptions—the metaphysic with which they operate.

Hans’s great 2011 book Heavenly Participation: The Weaving Of A Sacramental Tapestry is a must-read to go deeper into this understanding, which was universal in Christianity of roughly the first thousand years of the faith, and which is still fully present in Eastern Orthodoxy, mostly there in Catholicism, and can be found in certain forms of Protestantism (such as Hans’s Anglicanism).

What the Swedes and I ended up talking about is how the crisis of our civilization, including contemporary Christianity, comes down to a loss of enchantment. What do I mean by that? The abandonment of a sense that everything is in a mystical sense charged with the energy of God, that all things are connected and unified in the Logos, and that we can (and must) participate in the Logos. As I keep saying in this space, it is one thing to affirm with our minds the truth of the Christian faith, but it’s another thing to participate in those truths, to embody them.

To speak of “enchanted Christianity” ought to be an absurdity, but it’s not anymore. As the anthropologist T.M. Luhrmann has written, studying Evangelical Christians in the West, and how they pray and experience God, reveals something meaningfully different than studying Evangelicals in Africa and in India. Christians living outside the West have a far more palpable sense of the Holy Spirit’s presence in their everyday lives. This is not because they are necessarily better Christians than their American brothers and sisters. This is because they grew up in a culture that is far more open to the spiritual dimension of existence.

Wade Davis, an ethnobotanist who has written extensively about the disappearance of traditional primitive cultures in the modern world, says it makes a real difference whether or not you grow up believing that a mountain has deep spiritual meaning embedded in its material substance, or you think it is just dead matter ripe for exploitation. Many of us might react initially by saying that’s just animism, the belief that the mountain is some sort of deity, or a living entity. Animists might believe that, but that isn’t Christian. What is sacramentally Christian is the concept that the mountain, while being created by God, contains embedded within its material being part of the Logos. In Orthodoxy, we have a theological way of explaining this, which is not really necessary to get into here. The main point to take is that the mountain is in some real sense an icon of God, something that participates in His being and discloses it, and therefore can never be treated as only stuff.

As Hans says above, even if this sounds silly to you, you need to accept that you too have a metaphysic. It is a modern metaphysic, even if you are a confessing Christian. Indeed, it is a modern Western metaphysic. This is why in Living In Wonder, I talk near the beginning about the whole WEIRD concept — Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. This is the umbrella term that anthropologist Joe Henrich came up with to describe the basic way all of us modern people see reality, by virtue of having been born into this culture. It is liberating, actually, to come to see that what everyone around us considers to be unquestioned (metaphysical) truth is actually just one take — and a take that relatively few people on the planet share, because it emerged out of a culture that is educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic.

Understand what I’m saying: it’s not that we are wrong about everything, but that we in the post-Christian, materialist West are epistemic outliers in the world, and indeed outliers in our own civilization’s history. Iain McGilchrist and Charles Taylor are two great thinkers of our time who explain how this came to be.

OK, but so what? It might be nice to live in so-called “enchanted Christianity,” you say, but I’m fine with going to church on Sunday, reading my Bible, and living as faithfully as I can every day. Is that not enough? It’s enough for me.

Yes, it is true that deep Christian enchantment is not strictly necessary to live a godly life. The plodding businessman who never had a mysterious or awe-inspiring moment in his life, but who nevertheless worships faithfully, with a clear mind and a full heart, and lives a life of charity and compassion, is much closer to the Kingdom than a flighty woo-seeker who focuses on miracles, apparitions, and the like, but who can’t be bothered to do the boring, everyday acts of discipleship. Early in my life as an adult Christian, I was tempted by that world. It’s like crack for a certain kind of person.

So: why is enchanted Christianity so important — indeed, even urgent? In short, because its true, and it draws you closer to living in truth. In the book, I tell the story, familiar to all you readers, of my old friends “Nathan” and “Emma,” a Manhattan couple who suffered a terrible ordeal when it emerged that Emma was demonically possessed. Though they were both faithful Catholics, the enemy found an entry into Emma’s soul mostly because unknown to her until her exorcism, her grandfather back in Europe had made a pact with demons. When they had a sense of what was going on, the Archdiocese of New York sent Emma to see Dr. Richard Gallagher, the psychiatrist it uses to rule out any possible natural explanation for the phenomena in particular patients. Dr. Gallagher examined her thoroughly, and said there is no conceivable medical explanation for these symptoms.

I visited this couple during their long struggle for freedom, and was sitting there when Nathan provoked the demon to manifest through his wife by entering the room with a holy relic hidden in his pocket. This passage from the book tells how that evening ended:

After I said goodbye, Nathan, a businessman, walked me back to my hotel in Midtown. He had been struggling mightily to help his wife for two years, through a crisis that he never imagined would be possible for people like them: sophisticated big-city people who were faithful to the Mass and the sacraments.

“What’s the biggest way this has changed you?” I asked.

“Now when I walk down the street, I know that there is a spiritual battle going on all around me,” he said. “It’s everywhere. Once you have seen the things I have seen, you know it, and you can’t leave the fight.”

Nathan said that this was not a battle he ever would have chosen, but once it started, he knew he had a duty to see it through till the end.

I’ve known this couple for over twenty years, and though solid as a rock in their faith, they were very much not the woo-seeking kind. And yet, this happened to them. But it ended up making their faith far stronger, because, as Nathan avers here, it revealed to them the true nature of the everyday spiritual struggles we all have. Once you see this, you can’t unsee it — and that is a good thing, because having been “enchanted” by this long, frightening encounter with darkness, and seeing the power of God triumph over it, deepened and radicalized this couple’s faith.

Alasdair MacIntyre famously said that a person can’t know what they are supposed to do until they know of which story they are a part. The possession and deliverance drama revealed to this couple that the story of which they are a part — the story of the Bible, of the sojourn of God’s people through time — has a dimension that had been hidden from them. It turns out to be extremely important and relevant to daily life.

It’s like this: “For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms.” (Ephesians 6:12) It’s one thing to read that in Scripture and affirm it. It’s very much another to be with an old friend sitting right in front of you, and to watch her face change instantly, and her snarl curses at her husband for having on his body a blessed object that she couldn’t possibly have known about … and then watch her face return to normal, and hear her pitiful plea for mercy, saying, “That’s not me.” The words of Scripture come vividly alive, and it changes the way you move through this world. This is one reason it is important to move into the enchanted dimension of the Christian faith: for the clarity it gives you about reality.

Because enchanted Christianity teaches us to see the world sacramentally (see Hans Boersma above), it changes the way we treat matter — especially the human body. The stakes for this could not possibly be higher here at the dawn of transhumanism. Yesterday in The New York Times, Ari Schulman wrote a warning about how radically fertility technology is changing. Excerpt:

With major technological advances in childbearing on the horizon, what was once hypothetical is becoming plausible, setting the stage for a potentially tumultuous shift in the cultural mood about assisted reproduction.

Consider in vitro gametogenesis, or I.V.G., a technology under development that would allow the creation of eggs or sperm from ordinary body tissue, like skin cells. Men could become genetic mothers, women could be fathers, and people could be the offspring of one, three, four or any number of parents.

The first baby born via I.V.G. is most likely still a ways off — one researcher predicts it will be five to 10 years until the first fertilization attempt, although timelines for new biotech are often optimistic. But the bioethicist Henry Greely, noting the benefits of allowing same-sex couples to have genetic offspring and I.V.F. parents to pick the most genetically desirable of dozens or even hundreds of embryos, predicts that eventually a vast majority of pregnancies in the United States may arise from this kind of technology. Debora L. Spar, writing about I.V.G. for Times Opinion in 2020, echoes the view that such advances seem inevitable: “We fret about designer babies or the possibility of some madman hatching Frankenstein in his backyard. Then we discover that it’s just the nice couple next door.”

More:

The irony of the science fiction story “Gattaca” is that the most oppressed character was not the one at a biological disadvantage but the one whose parents’ designs for him were forever written into his biology. His life was not fully his own.

It’s remarkable that this idea is so omnipresent in our culture and yet has little to no purchase in how we think about today’s reproductive technologies. …

You see what I’m getting at? As Ken Myers of Mars Hill Audio often says, “Matter matters.” If we think of our bodies as mere matter, as material extensions of our will, there is no stopping any of this. True, many Christians oppose these things for solid reasons that have nothing to do with “enchantment.” Yet discovering the metaphysical basis of Scripture’s moral precepts serves to deepen and firm up one’s understanding of why God tells us to do certain things, and not to do others. This might sound like an abstract point, but it isn’t. To follow Wade Davis’s point: it makes a big difference if you see man as made in God’s image, and the human body as a kind of temple of God, whose treatment must be ordered by God’s laws; and seeing it as nothing but material to be mined and conformed to one’s own will. This could hardly be more clearly manifest than in the way we think about childbearing.

In my last book, Live Not By Lies, Christians who lived through Soviet communism and its persecutions say that the capacity to endure suffering is the most important factor in determining whether or not one can resist being crushed, and can come through with one’s faith intact. It is easier to suffer if you are confident of the ultimate transcendent truths — and the Truth — for which you offer sacrifice.

In Living In Wonder, I talk about psychiatrist and Holocaust survival Dr. Viktor Frankl’s teaching, most of all in his great book Man’s Search For Meaning, that we can endure most anything if we are convinced that there is meaning in our suffering. You will recall from the last book the story about how the tortured prisoner Alexander Ogorodnikov, jailed for being a Christian, recovered his flagging faith after repeated visitations to his dank cell by angels bringing him visions. The sheer vivid reality of the transcendent realm made visible brought the agonized prisoner’s belief in God’s presence and plan back to life from its near death.

Dr. Frankl talks about that sort of thing. But there’s also the matter of how being struck out of the blue by a hierophany, a sudden showing of the sacred, saved Whittaker Chambers from his slavery to Communism. I mention both men in this passage from Living In Wonder:

If the cosmos is constructed the way the ancient church taught, then heaven and earth interpenetrate each other, participate in each other’s life. The sacred is not inserted from outside, like an injection from the wells of paradise; it is already here, waiting to be revealed. For example, when a priest blesses water, turning it into holy water, he is not adding something to it to change it; he is rather making the water more fully what it already is: a carrier of God’s grace. If we do have an experience of awe, a moment when the fullness of life is suddenly revealed to us in an extraordinary way, it is more likely to be far more ordinary than a mystical cleansing cloud blowing in from the River Jordan.

We might be like the Austrian Jewish psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl, who, as a ragged inmate digging a trench in a German concentration camp, tried to drive away the despair engulfing him by thinking of his faraway wife. Frankl writes that he suddenly “sensed my spirit piercing through the enveloping gloom. I felt it transcend that hopeless, meaningless world, and from somewhere I heard a victorious ‘Yes’ in answer to my question of the existence of an ultimate purpose. At that moment a light was lit in a distant farmhouse, which stood on the horizon as if painted there, in the midst of the miserable grey of a dawning morning in Bavaria. ‘Et lux in tenebris lucet’—and the light shineth in the darkness.”

Dr. Frankl found the strength to go on that day—and later in his life, to help untold millions through his books about finding meaning in suffering.

Or we might have an experience like the Soviet spy Whittaker Chambers did in the late 1930s, which ultimately led him out of the Communist underground. He was at home watching his adored baby daughter eating in her high chair. “My eye came to rest on the delicate convolutions of her ear—those intricate, perfect ears,” Chambers wrote. “The thought passed through my mind: ‘No, those ears were not created by any chance coming together of atoms in nature (the Communist view). They could have been created only by immense design.’ The thought was involuntary and unwanted. I crowded it out of my mind. But I never wholly forgot it or the occasion. I had to crowd it out of my mind. If I had completed it, I should have had to say: Design presupposes God. I did not then know that, at that moment, the finger of God was first laid upon my forehead.”

None of us know what is coming, but many of us believe the passing away of a civilization built on a Christian framework is going to bring nothing good. It could mean martyrdom, both bloody and bloodless. Or we might be tempted to allow our faith to bleed out slowly, under pressure to conform to the post-Christian order.

A friend told me recently about a couple he knows who used to be strong Christians, but who always, in his view, had a weakness for the need to be the coolest people in the room. Eventually they “deconverted” — renounced their Christian faith. This didn’t happen under torture or persecution. It happened because of their vanity. If you have become the sort of Christian who lives in an enchanted way — that is, with an awareness of the reality and closeness of the numinous aspect of reality — it is much harder to fall victim to this kind of rationalization, or so it seems to me.

Again, enchantment doesn’t make you a more worthy Christian in the eyes of the Lord, but it does give you an irreplaceable weapon in the spiritual war of our time and place. When the Jesuit Karl Rahner said that the Christian of the future will be a mystic, or he won’t be anything at all, he meant (I think) that in the emerging post-Christian world, those who hold on to the faith will be those who have had a numinous experience (that is, an experience of mystery and wonder), and who know beyond a shadow of a doubt that God is real. In a time and place where rationality and post-Christian (even anti-Christian) cultural standards make it hard to hold on to the faith, those who have been enchanted have stronger ground to stand on.

We have the idea that the mystic is a rare person with special gifts of spiritual insight and experience. That’s not what Rahner means. Rather, he was trying to convey that mysticism, in the sense of experiencing the Holy Spirit in the everyday, must become common among the faithful. It’s funny, but Orthodoxy has a reputation for being the most mystical form of Christianity, and it’s true if you come into it from the West. But nobody in Orthodoxy ever talks about “mysticism” for the same reason the fish don’t talk about sea: because it is the water in which we swim. For the Orthodox, what Westerners call mysticism is just … normal. I didn’t write this book as an apologetic for Orthodoxy, but I do hope at least that readers from the Catholic and Protestant traditions can accept the gift of mysticism as a normal part of being Christian that we Orthodox bring to our common table as followers of Christ.

There’s another urgent reason to seek out enchanted Christianity, one I didn’t perceive until I worked on this book. Marshall McLuhan, who was a daily massgoer, once wrote that every person he knows who lost the faith began their journey to deconversion by ceasing to pray. The implication is not that they set out to deconvert, but that having lost that living daily connection to God, the living waters and source of life, eventually their capacity to believe dried up too. Well, what I discovered in doing this book is that the capacity to sustain attention is far more important to the spiritual life than I realized.

Here’s a Living In Wonder passage speaking to this point:

It is a truth well established, but not widely appreciated, that our technologies change the way we perceive the world. Many people believe that the internet is nothing more than an information-delivery device. Not true. As media theorist Marshall McLuhan famously said, “The medium is the message.”

He means that the means by which we receive information matters more, on the whole, than the information received. Why? Because the medium determines “patterns of perception,” the mental framework with which we take in the information. The invention of mechanized printing, for example, trained the Western mind in linear ways of thinking that had both positive and negative effects over the centuries.

“All technologies are extensions of our physical and nervous systems to increase power and speed,” says McLuhan. If, say, the invention of a mechanical digger extends the power of our hands, or the invention of the automobile magnifies the power of our feet to provide locomotion, then, argues McLuhan, the advent of electronic media amounts to externalizing our entire nervous system. If so, we are all extraordinarily vulnerable to outside manipulation.

McLuhan, who died in 1980, did not live to see the internet, though it is a fulfillment of his prophecies. In his classic 2010 book The Shallows, journalist Nicholas Carr observes that since he began relying on the internet, he has suffered a diminished ability to concentrate, an experience familiar to many of us. There are neuroscientific reasons for this, Carr found.

Though most of our brain’s structure comes to us from our genetic code, that’s not the whole story. Neuroplasticity is a biological fact. The brain is malleable, within limits (it is not elastic), and can change depending on the environment in which an individual lives.

For example, people who go deaf develop other senses in their brains to help compensate for the loss of hearing. People who speak different languages have slightly different brains, likely owing to the particularities of a language’s structure and orthography. In one experiment, scientists found that the brains of London cabbies, who are required to memorize the entire streetscape of the British capital, are anatomically different from normal brains, in that they have more space devoted to the capacity to store spatial memory. This is what Harvard’s Joe Henrich means when he says mass literacy after the Reformation altered the way Western man’s brain worked.

Our brains were not made to function with internet technology. It renders the task of understanding what we perceive much more difficult. … It’s not just the internet but the ubiquitous way most of us access it: through the smartphone. Neuroscientists have found that the constant bombardment of information coming through the black-mirrored devices blitzes the prefrontal cortex, where most of our reasoning, self-control, problem-solving, and ability to plan takes place. The brain’s overwhelmed frontal lobes wind down higher-order cognition and defer to its emotional centers, which spark a cascade of stress and pleasure hormones.

Because the internet produces exactly the kind of stimuli that quickly and effectively rewire the brain, Carr says that it “may well be the single most powerful mind-altering technology that has ever come into use.”

Fine, but why is it a disenchantment machine? Because the internet destroys our ability to focus attention. The unruly crowd of competing messages jostling for the attention of our prefrontal cortex not only makes it harder for our brains to focus but also renders it far more difficult for us to form memories. This is because, for lasting memories to lodge in our minds, we need to process the information with sustained attention. Using the internet creates brains that cannot easily remember. As we will see later in this book, it also creates brains that cannot easily pray, which is the main and most important way we establish a living connection to God.

More:

It turns out that attention—what we pay attention to, and how we attend—is the most important part of the mindset needed for re-enchantment. And prayer is the most important part of the most important part.

It’s like this: if enchantment involves establishing a meaningful, reciprocal, and resonant connection with God and creation, then to sequester ourselves in the self-exile of abstraction is to be the authors of our own alienation. Faith, then, has as much to do with the way we pay attention to the world as it does with the theological propositions we affirm.

“Attention changes the world,” says Iain McGilchrist. “How you attend to it changes what it is you find there. What you find then governs the kind of attention you will think it appropriate to pay in the future. And so it is that the world you recognize (which will not be exactly the same as my world) is ‘firmed up’—and brought into being.”

We normally pay attention to what we desire without thinking about whether our desires are good for us. But that is a dangerous trap in a culture where there are myriad powerful forces competing for our attention, trying to lure us into desiring the ideas, merchandise, or experiences they want to sell us.

Besides, late modern culture is one that has located the core of one’s identity in the desiring self—a self whose wants are thought to be beyond judgment. What you want to be, we are told, is who you are—and anybody who denies that is somehow attacking your identity, or so the world says. The old ideal that you should learn—through study, practice, and submission to authoritative tradition—to desire the right things has been cast aside. Who’s to say what the right things are, anyway? Only you, the autonomous choosing self, have the right to make those determinations. Anybody who says otherwise is a threat.

What does this have to do with enchantment? The philosopher Matthew Crawford writes that living in a world in which we are encouraged to embrace the freedom of following our own desires—which entails paying attention only to what interests us in a given moment—actually renders us impotent. He writes, “The paradox is that the idea of autonomy seems to work against the development and flourishing of any rich ecology of attention—the sort in which minds may become powerful and achieve genuine independence.”

If one’s capacity to pay sustained attention is weakened or lost, we lose spiritual power, and we also lose our capacity to pray (which requires sustained attention). I struggle with this every day, and often lose — but at least I know I’m in a struggle. To surrender to the disenchantment machine that is the Internet is to surrender unawares the ability to keep one’s eyes on God. Very few of us can do without the Internet. I make my living with it, and if I tell you that it deeply affects one’s ability to pray, I’m speaking from experience. My greatest spiritual challenge is to fight back against the fragmenting effect of spending most of my day on the Internet.

I don’t think most Christians are really aware of how this ubiquitous technology is a kind of spiritual kryptonite, not because it tempts us to look at porn or other bad things, but because of the way is affects us neurologically, and the effect it has on our capacity to pay attention. Living In Wonder brings this out, and, I hope, will begin to reverse the spiritual disarmament to which all of us have fallen victim.

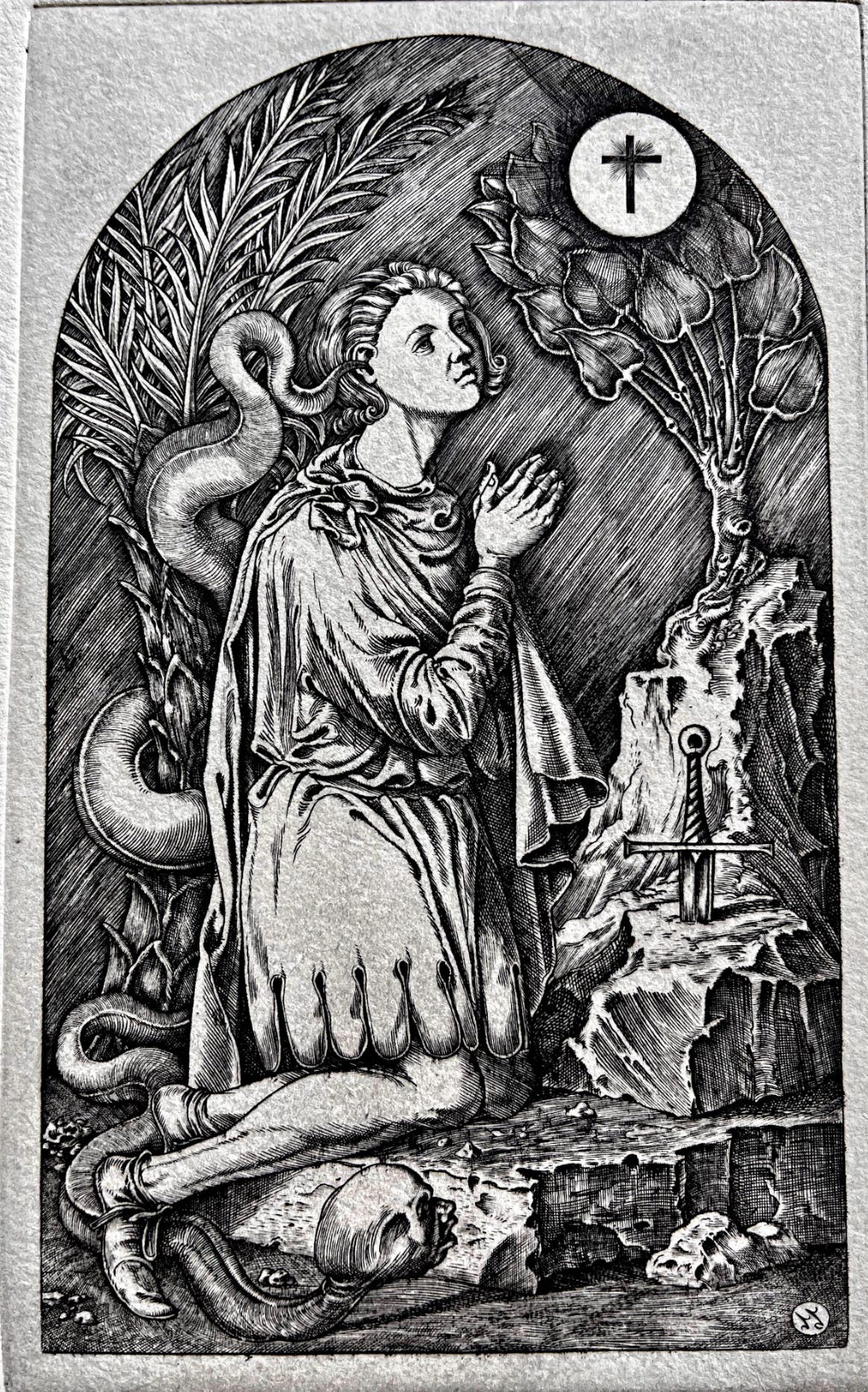

You know this book’s genesis is the gift the artist Luca Daum gave me that night in 2018 in the oratory church in Genoa, his city. He didn’t know why he was doing it; he told me the Holy Spirit spoke to him in prayer, and told him to do so. It was this engraving titled “The Temptation of St. Galgano”:

Now, you’ve all seen this image a hundred times in my Substacks. But I want you to look at it in light of what you read just a second ago about attention, and what you read earlier about a mystic being, in Rahner’s words, “someone to whom something has happened.” Galgano Guidotti was a violent man of the 12th century who resisted conversion until a stunning miracle happened to him: his sword went into a rock. You can see it for yourself if you go to the top of the hill in Tuscany where it happened.

The sword in the stone is both evidence of the miracle and a symbol of his surrender of his will to God after experiencing it. God showed him reality beyond what his reason could comprehend. His temptation, rendered by the artist as a serpent coming from his ear, is distraction — thoughts trying to draw his attention from God.

This engraving condenses the core message of Living In Wonder: that when we experience a theophany (or hierophany) — a miraculous showing-forth of God and the sacred order — we must surrender our will to the God we have seen. This is what Galgano bending his knees means. And we must cultivate the spiritual and mental discipline, chiefly through prayer, to keep our eyes firmly fixed on God.

If not? We risk forgetting the story of which we are a part, and thus risk our faith becoming a hollowed-out thing, an impotent thing, and even apostasy. It is therefore urgent that we turn towards wonder, in a Christian sense, and make it central to our lives in this disenchanted world (or otherly enchanted, because so many in postmodernity are falling now into the occult, or to other forms of false enchantment).

This is nothing new. This is something very old for Christians. It is how all Christians saw the world in the first millennium. St. Thomas Aquinas, the most brilliant of all Christian rationalists, saw it at the end of his life, when, having a mystical vision, he told his secretary that everything he had written is like straw compared to what God showed him. Charismatic Christians today, whatever my theological disputes with them, they get it too. Anglicans like Hans Boersma get it. And you know, my publisher Zondervan, the biggest Evangelical publishing house in the world, gets it, which is why they have put themselves behind this work by an Orthodox Christian writer. This message is for all Christians, and it is written in the same spirit as The Benedict Option and Live Not By Lies: to help us stay faithful in a time of desolation.

As I explain in the book, you cannot force theophanies to happen. They are a gift of God. What you can do, though, is to cultivate the spiritual awareness within yourself to be open to them — both big theophanies, like Galgano’s miracle, and the small ones in which God shows himself to us. Because I had been doing that for years, I knew that the artist approaching me in a foreign church, on what he said was the Holy Spirit’s prompting, was not just one of those things. It meant something. If that man, Luca Daum, had not done that, there would likely be no Living In Wonder, a prophetic and urgent message to the church in these dark times.

Don’t think this book is mostly about learning a cool way of living out the faith, one that makes us more sensitive to the ways God speaks to us, like through beauty. It is that, but it is much more: it is about waking us up to the deepest aspects of the reality in which we live, and teaching us how to find spiritual strength there — the kind of strength that all of us, no matter what our faith tradition or station in life, need if we are going to endure faithfully this time of trial.

I have been living with this book for so long that I really have no idea how it’s going to be received. Seeing how my Swedish interlocutors — not Christian or barely Christian but searching — reacted to hearing it for the first time gave me hope. It made me think that this book might really be powerful. One of them said he was baptized in the state church, which, in his telling, has become a theological cesspit. He recently baptized his son there, mostly out of cultural habit, and was told by the woman priest that he didn’t really have to believe in God. Living In Wonder, a PDF copy of which I sent to the guys after the recording, will show them that the world is not what they think it is, and that there is so very much more to Christianity than what they see. It will do the same for you too.

I know that I’m going to take some reputational hits for this book, because in it, I out myself as a complete Christian weirdo. I don’t care. It’s important. We are past the time when Christians can stay quiet because they are afraid of seeming weird. At the very end, I tell for the first time about a mystical vision I had in 1993 — the only time that has ever happened to me. I don’t say what was revealed, but I will say that it was a vision of mass deception and destruction, spiritual and otherwise. As I write, there were aspects to this experience that, on that very night, convinced me beyond a shadow of a doubt that this was no hallucination, but was real. This came at the beginning of my adult Christian life, and near the start of my career as a journalist. I kept this message deep within me, and built my understanding of events on it — the kinds of events I have spent most of my career writing about.

Lo, three decades on, I have lived to see it all come true. If time stopped today, the vision will have been fulfilled. But I see that it is still unfolding. If this strange vision had not come to me, and if I hadn’t taken it seriously, as Galgano took the sword in the stone, I don’t know where I would be today as a Christian. I probably would have succumbed to the confusion and apostasy that God showed me was coming. I have shared the entire vision with a few people over the years, from the beginning, but I don’t feel at liberty to talk about the core aspect, at least not yet. Suffice it to say that if you consider how the faith has fallen apart, and our culture and civilization have disintegrated in the past thirty years, you understand enough of the terrible revelation I saw that cold night in my apartment in Washington.

You will soon have this book in your hands because of what happened that night so long ago, because the artist in Genoa obeyed God in delivering his engraving to me, and because of so many other signs and wonders that have been part of my life, and the lives of so many others I’ve met, some of whose stories I tell in Living In Wonder. It is an invitation to experience God at a depth you may not have thought possible. It is also a call to living within a prophetic Christian mysticism of the sort that must become normalized in the lives of churches and individual Christians struggling to hold the line in these apocalyptic times. If not, we might not make it. This is no exaggeration.

As dire as things look now, the struggle has really only just begun. Prepare. You don’t have all the time in the world, which, believe me, is not what you think it is.

Prayer is unbelievably important. I lost my younger brother last week, and like every other time death kicks in the door, I pray more fervently. The problem for me is sustaining it. I eventually reach the desert and it becomes a struggle. Articles like this, podcasts, and books help, so thank you.

I remember an old saying that the prayers of monks sustain the world, but we living in the world have our work to do as well. Especially in these dark days.

Already ordered. Looking forward to it, Rod. Like most things of instruction in the Bible, "Pray without ceasing" is not in there to be poetic. We are to stay constantly in touch with God. Not only is it good to set aside a dedicated block of time to bring conversation and petition to the Lord, which I've been doing these last couple years, daily. But when something comes up you think you need to bring to the Lord, bring it. You are not inconveniencing him. Talk to Him. Bring your concerns to Him. His peace follows you throughout the day and you may see small movements and miracles around you.

Can't wait for your book, Rod.