The Wildness Of The 'Invisible Sky Deity'

And: Kamala's Plus Ça Change Candidacy; Medjugorje; The King & Hopkins

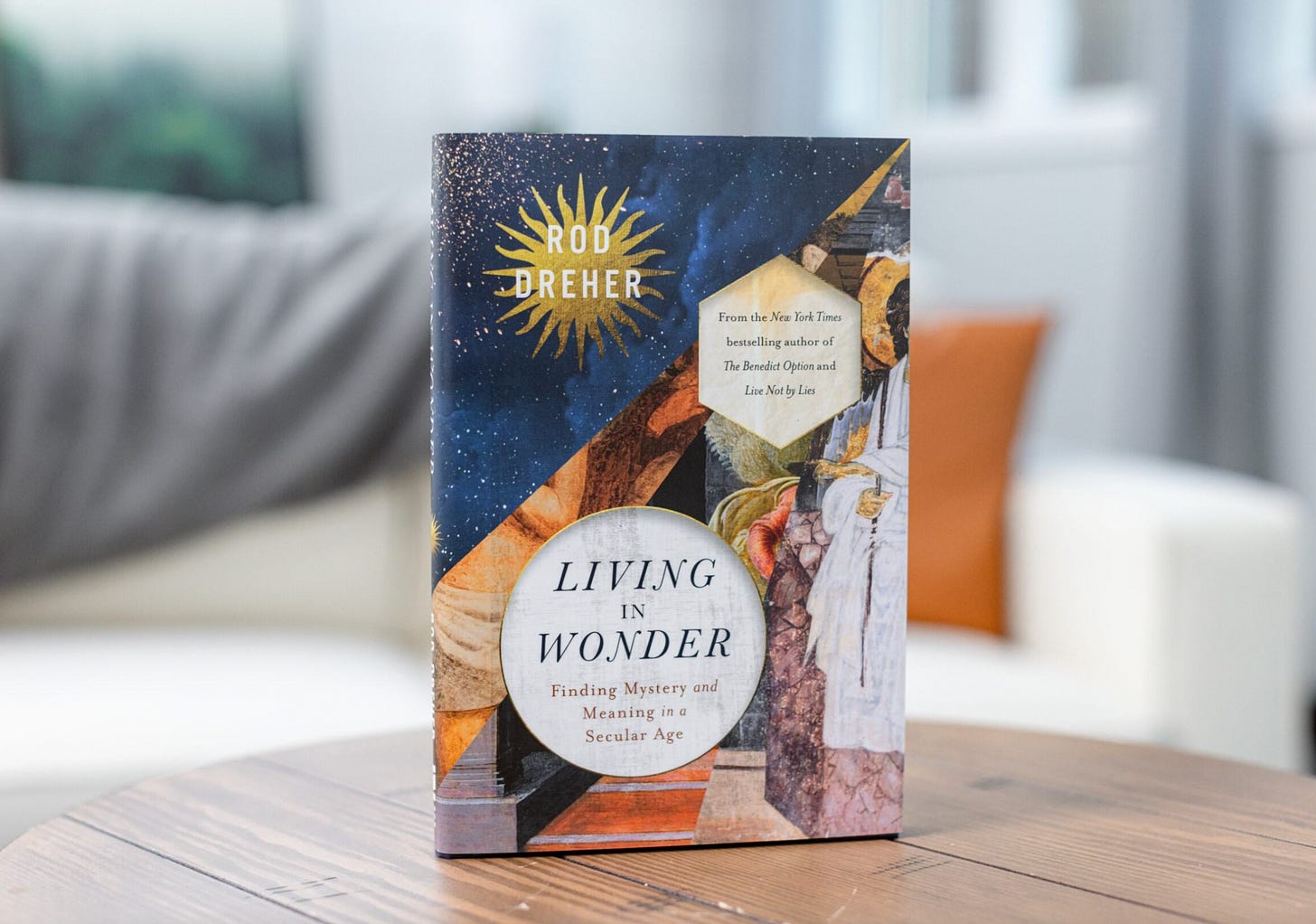

I want to apologize to you subscribers for all the Living In Wonder content that will be coming your way over the next few weeks, as we move toward the October 22 launch of the book. This is normal stuff as we try to get as many buyers on the launch week as possible. This is how a book makes it to the bestseller list. In most cases, a book sells more on opening week than it does after that. In the case of Live Not By Lies, we sold something like 15,000 copies on opening week, which landed it on the NYT list. We never again sold that many in a given week; though the book has now sold over 200,000 copies in the US, it never again made the bestseller list.

Reviews should be coming in soon. I’ve heard through the grapevine that two major Christian publications will publish glowing reviews, which naturally delights me. I expect that most secular publications will either ignore the book, as the did Live Not By Lies, or trash it. That’s fine — this is not a book for the woke or the militantly secular. I actually think there will be some curious agnostics who are interested in what it has to say, but most people who write for mainstream media will not get this book. If you work in conservative and/or conservative Christian publishing, you learn to expect this, and to not be bothered by it.

Yesterday Kirkus Reviews released its take on the book, and it was a hatchet job. Normally an author doesn’t want to draw attention to bad reviews, especially one that few people will see (Kirkus reviews typically signal to booksellers and libraries whether or not they’ll want to stock a title.) But this one was memorable, and important for what it says about the state of American publishing and media, and the world that small-o orthodox Christians live in. Next week I’ll be giving a speech at the Touchstone conference in Chicago, on why embracing Christian re-enchantment is a survival strategy for thriving in what Aaron Renn calls the Negative World. The Kirkus review actually exemplifies what I’ll be talking about. Here it is, in full:

An admittedly “strange book” about religious faith and its necessary willing suspension of disbelief.

It’s one thing to believe in an invisible sky deity. It’s quite another to believe in demons that require exorcism in UFOs, whose extraterrestrial occupants, one religious scholar believes, “are likely to be at the bottom of a new religion that will arrive in the future.” For the moment, Dreher writes, Christianity will have to do—and not just any Christianity, but its Eastern Orthodox variant, which retains the ecstatic and the mystical in place of more rational, less awestruck Western strands. Dreher is committed to bringing his reader to adopt this extrarational way of being in the world, his or her every breath devoted to religious practice. (Toward the end of the book, he prescribes the “Jesus Prayer,” its four simple lines punctuated by breath and spoken as if a mantra.) Dreher is capable of stirring exaltations, as when he likens humans to fish at the bottom of a pond: “Sometimes we catch a flash of light reflected in a piece of matter drifting down from on high, and our attraction to it causes us to rise toward the light beyond the surface,” he writes, going on to say that the beauty brought to humans by the arts fuels that gracious light. Regrettably, he also punctuates his argument with flashes of rightist thought, as when he describes American teenagers who convinced an Eastern European pal that she “might be genderqueer”—and so she might have been—and says that “witchcraft and paganism typically track with progressive political commitments, especially around feminism, environmentalism, and queer activism.” Such moments make it clear that Dreher’s “confident belief that there is deep meaning to life” doesn’t tolerate much wiggle room.

If you’re inclined to Orthodox fundamentalism, then this is your book. If not, not.

OK, first: what kind of general-interest review publication assigns a book about faith and mysticism, by a well-known Christian conservative writer, to a reviewer who uses phrases like “invisible sky deity” to describe God? You really don’t have to read past that line to know that this anonymous reviewer is an unreliable voice. It’s like asking Matt Walsh to review the latest Ibram X. Kendi tome.

The book does indeed speak of demons, in which I believe, and in which all Christians who take the Bible seriously must believe. The UFO mention here gives you no context for the discussion in the book. I’m clear that I never took UFOs seriously, until digging into the story and its religious elements changed my mind. Diana Pasulka, the religious studies academic who researches UFO belief as an emerging religion, tells me that it really is happening. Attention, therefore, must be paid. I thought the UFO stuff was all silly — but I was wrong.

I do write about Orthodoxy, but in a mode of sharing with all readers — most of whom will not be Orthodox — the practices and insights that Eastern Christianity has to share with the Western church, to help recover a more “enchanting” sense of God. I deliberately set out not to be an Orthodox apologist here. And what is this “Orthodox fundamentalism”? There is no such thing; “fundamentalism” is a swear word that leftists and secularists use to condemn forms of Christianity they find distasteful.

Living In Wonder is not a political book, or a culture-war book. But the Kirkus reviewer found one negative mention of “genderqueer” — this in a chapter mentioning how an 11-year-old girl in Europe was radicalized on gender through her smartphone, while her folks didn’t know what was going on; she is now paralyzed with depression — to condemn the book as having “flashes of rightist thought.”

Well, sure, that’s true: the book argues from a position of Christian orthodoxy. The quote about “progressive political commitments” are not my words, but those of Tara Isabella Burton, an academic analyst who explains why the embrace of witchcraft and pagan religion tracks closely with left-wing political commitments. The reviewer doesn’t like my politics or my Invisible Sky Deity religion, so he or she ignores acres of material about anthropology, psychology, history, technology, and so forth.

You see what’s going on here: the Kirkus reviewer is signaling to libraries and bookstores that Living In Wonder is bigoted hatecraft. I will not be surprised if many libraries and bookstores decline to stock it after that review. Happily, we now have ways of bypassing these gatekeepers. You can pre-order online from Eighth Day Books (which is exclusively selling signed copies). You can pre-order from Amazon, or any online retailer. I have no doubt that the book will find its readers, just as Matt Walsh’s new comedy documentary Am I A Racist? is doing well with audiences, despite being totally ignored by critics.

That said, it’s interesting to see how the Media Industrial Complex works to marginalize and punish dissenters from its narrow worldview. I would not complain about a review that found the book unsatisfying, as long as the reviewer seemed to read it fairly and take its arguments seriously. A critic who bitches about people who believe in an “invisible sky deity” brings to the book an agenda that makes a serious reckoning with the text impossible.

This matters in part because, as I explained, Kirkus is an invisible gatekeeper. Relatedly, it matters because the kind of people who are in positions of authority to shape the culture hold these kinds of prejudiced views, and surround themselves with ideological allies. Over the past decade or so, I’ve had numerous conversations with people inside various institutions and companies who live deeply closeted lives in terms of their religion, their politics, and their cultural beliefs. They know perfectly well that if they were to “come out,” so to speak, they would be pushed out.

It was wrong when society did that to homosexuals, and it’s wrong now. But like Woody Allen’s character quipped in Annie Hall, “Yes, I’m a bigot — but I’m a bigot for the Left!” Anyway, it’s important for orthodox Christians and non-progressives of all kinds to understand how this stuff works. If you don’t see Living In Wonder in your local bookstore or library, the Kirkus review might have had something to do with it. And once again begging your pardon for all the Wonder-posting now and to come, it’s one of the only ways I have to get past the information gatekeepers.

This review, and future secular reviews, which will no doubt focus on the weirdest aspects of the book — demons, UFOs, and such. What you won’t see is how much utility there is in Living In Wonder — practical advice for how to live in a way that opens you up to the possibility of enchantment. Kirkus mentions the Jesus Prayer as if it were some kind of freaky-deaky thing (“mantra”), when in fact it is a very common spiritual practice of Eastern Christians, even Byzantine Rite Catholics. I teach readers how to employ it. From the book:

I’ve spoken about the Jesus Prayer, which emerged early in the Christian era from the monasteries of the desert fathers: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me.” A letter from Saint John Chrysostom (d. 407) cites that formulation as being in use for ceaseless prayer. A later version, the one typically used today, adds two words to the end: “a sinner.”

In the late medieval period, monks of the Eastern church popularized the use of this prayer for personal devotions. They call it hesychasm, from the Greek word meaning “stillness.” The Jesus Prayer is still widely used among monks and laity in the Orthodox churches but is also recommended by the Catholic Church for its communicants. The late Anglican bishop Simon Barrington-Ward was an enthusiastic advocate of the Jesus Prayer, which he learned personally from Saint Sophrony of Essex, a contemporary Orthodox monastic.

The Jesus Prayer is about achieving inner stillness, through which one communes with the presence of God. It is not a technique; the prayer will do you no good if it is not part of an overall life of repentance and holy living. But if it is used in the prescribed manner, the Jesus Prayer draws one slowly but inexorably out of spiritual blindness and into a world enchanted by God’s presence. Trust me on this.

There is general agreement among spiritual fathers on how to begin practicing the Jesus Prayer. The praying person usually uses a woolen prayer rope made of knots, but this is not strictly necessary. You find a calm place, sit quietly for a few minutes to gain inner stillness, then begin to say, aloud, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

Soon you can move on to praying this silently (in fact, silence is how I was taught to say the Jesus Prayer from the beginning, but not all spiritual fathers agree). Breathe in deeply and regularly as you pray:

Lord Jesus Christ [inhale],

Son of God [exhale],

have mercy on me [inhale],

a sinner [exhale].

Don’t rush; go slowly, and allow the rhythm of your slow breathing to make you tranquil.

The hardest part of this is to clear your mind during the prayer. You have to do this by acts of the will. The monks teach that one’s consciousness should be free of any extraneous thoughts—even images of Jesus. This is incredibly difficult at first. As I mentioned earlier, when I prayed it during my chronic illness, thoughts flew across my conscious mind like bullets on a battlefield. But I persisted in resisting them, and because I had been warned about this by my priest, I did not get discouraged through these trials.

Orthodox spiritual practice calls these unwanted thoughts logismoi and trains Christians, both in prayer and in ordinary life, how to refuse them. Eventually you gain sufficient control of your mind such that logismoi—even wicked ones, like temptations—are a threat more easily handled.

After some time—the length depends on your progress in prayer—the heart and mind begin to work together to say the Jesus Prayer. This is something that comes with experience. It happened to me during the first months that I prayed the Jesus Prayer devoutly, shortly after my conversion, but I carelessly put the practice aside. Even more foolishly, years later, I stopped once again after my body was healed from chronic illness. We mortals are weak and waste our gifts in scattering.

If it happens, though, you feel as if the prayer emanates from deep within your heart. It brings with it an inexpressible sweetness of communion with the Holy Spirit.

And then, if one is especially devout, the prayer becomes rooted in the heart and begins to hum like a generator of light, running on its own. This mystical experience has been widely attested to by monks and others who are advanced in the Jesus Prayer.

Again: the Jesus Prayer is not a mere technique, like sit-ups. If it is not said with total attention to Christ, it amounts to what Scripture condemns as “vain repetition.” And if it is not part of an overall life of practice toward holiness, it won’t do you much good. But for those who have the patience to learn the practice and live by it, integrating it into an overall life of fidelity, the Jesus Prayer is a potent means of allowing oneself to be drawn into union with Christ and into peaceful resonance with the world he created.

This is a good example of what I hope to do in the book: introduce Eastern Christian ways of praying and thinking about the relationship between God and Creation to Western Christians, to help them in their own Christian lives. It would thrill me if a reader finished the book and decided to visit an Orthodox Church, and maybe even to convert. But I don’t expect it, and I certainly didn’t write the book with that in mind.

The other day Andrew Brunson, the well-known American Evangelical pastor, to whom I once introduced to the Jesus Prayer, told me that not long ago, he was in a situation of high stress, and remembered the prayer. He prayed it as I taught him to, and he said he became calm and filled with God’s presence. This made me very happy.

The Jesus Prayer is an ancient prayer discipline that can be used by Christians of all confessions. Elsewhere in the book, I draw on the anthropological work of Stanford’s T.M. Luhrmann, who embedded with the Vineyard church movement to observe how they pray and read Scripture, seeking to make God “real” to them (that is, to feel His presence). The Vineyard folks are Protestants from the Evangelical tradition, but they have things to teach all of us Christians who are struggling to walk more closely with Christ. The book also has testimonies from Catholics, about how the Holy Spirit reached them.

“Orthodox fundamentalism” my foot! Naturally there will be parts of the book that some Christians can’t accept on theological grounds, but that’s okay. There is, I believe, enough practical information and advice in it to make Living In Wonder well worth reading. If you agree, then please tell your friends about it. Yes, I am an Orthodox Christian, but I try hard to be a servant of Christ first of all, and a servant to His people, wherever they may be. This is the result of God allowing me to be shattered by my own intellectual pride earlier in my Christian life. I am not an Orthodox triumphalist; I’m an Orthodox Christian, but I’m not angry about it.

I received my Orthodox faith as a gift and a balm, and want to share whatever I can of it with anyone who cares to ask. The fact that Living In Wonder is being published by Zondervan, the leading Evangelical publisher, tells you something about the kind of book it is.

If you’re inclined to practical Christian mysticism, cultural criticism based in traditional metaphysics, and tales of the supernatural (miracles, spiritual warfare, etc.), then this is your book. If not, not.

After the break is content for paid subscribers, including a bit on Nick Cave’s acclaimed new album, Wild God. Why not consider becoming one? It’s only six dollars per month, and you get at least five newsletters per week, as well as the opportunity to participate in a lively but civilized comments section.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rod Dreher's Diary to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.