War Of The Worlds

And: Andrew Doyle Leaves Britain; The Ben Op As Response To Church Decline

I am not able to tell you where this idea comes from, but I can assure you that, from my sources, it’s not idle speculation. Thesis: the drones are from China.

China is taunting us, showing us how advanced its technology is, and that it can violate US airspace with impunity. We don’t have the ability to detect these things before they arrive, and they can cloak themselves from our radar. I had wondered why China or any nation would reveal its advanced technology in this silly way. A possible answer: it could be a display of power in advance of an invasion of Taiwan, as a kind of “Are you sure you want to mess with us, Yanks?” way. Doing this could be a shrewd way of firing a warning shot.

If it is China, why wouldn’t we shoot them down? Possible answer: because it is too humiliating and destabilizing to admit that the Chinese, or any adversary, can do this to us. If you’re the government, it may be better to say, “We don’t know what this is” than to concede the humiliating truth. What’s more, to shoot them down would mean a dramatic escalation with the Chinese. It could be that the Biden administration reckons that it’s not worth risking war with a superpower, especially one that possesses this kind of technology, over this.

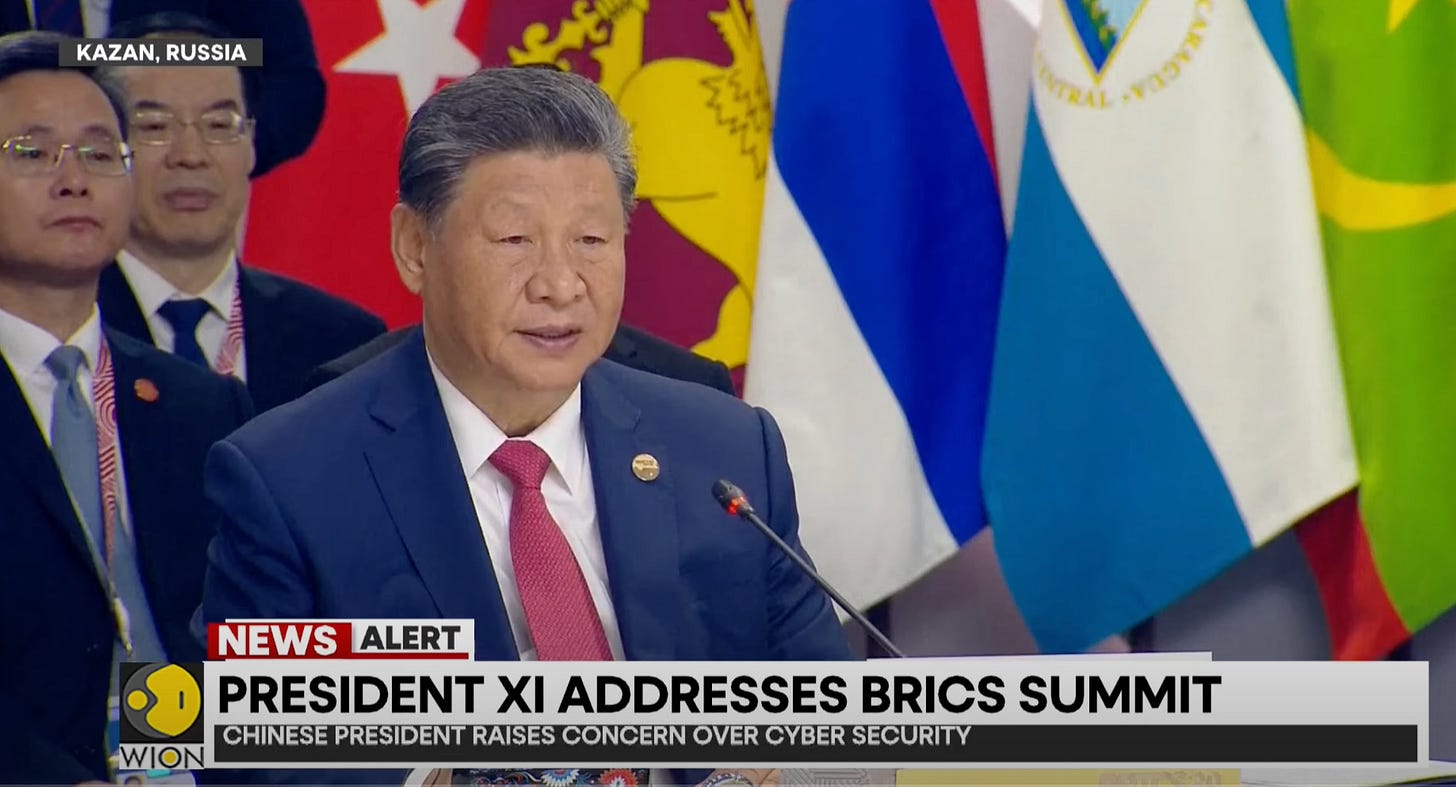

Related, here’s a scary-as-hell op-ed in The New York Times. I’m using one of the gift links I get as a subscriber to open this up for you all; it’s that important. The authors quote a speech Xi Jinping gave not long ago at a BRICS meeting:

“Should we allow the world to remain turbulent or push it back on to the right path of peaceful development?” Mr. Xi asked. He invoked, as a spiritual guide for the task ahead, an 1863 Russian novel that glorified revolutionary struggle and inspired Vladimir Lenin.

Mr. Xi has frequently drawn on Russia’s historical and literary tradition to convey his intent to undermine — and ultimately displace — Western ideas and institutions. But by urging a spirit of revolutionary sacrifice within BRICS, a group that is expanding to include new member-states, Mr. Xi is signaling an intent to rally the developing world for an intensified struggle against American power.

The obscure and radical novel that the Chinese leader cited as his inspiration offers a glimpse into Mr. Xi’s mind-set as he prepares to test Donald Trump’s commitment to the institutions and alliances that underpin the U.S.-led order.

The novel is What Is To Be Done? by Nikolai Chernyshevsky. It is considered to be the inspiration for the Bolsheviks, who declared its author to be “the father of the Revolution.” If you know anything about modern history, the idea that this evil book inspires Xi Jinping sends a jolt down your spine. The novel glorifies a revolutionary who stops at nothing to harden his mind, body, and spirit for the struggle ahead. More:

Mr. Xi invoked precisely this ethos of sacrifice and fortitude at the BRICS summit, telling other leaders that Rakhmetov’s “unwavering determination and ardent struggle encapsulate exactly the kind of spiritual power we need today. The bigger the storms of our times are, the more we must stand firm at the forefront with unbending determination and pioneering courage.”

Perhaps tellingly, China has downplayed the radical nature of Mr. Xi’s program for Western consumption, airbrushing his reference to Rakhmetov out of official English transcripts of his remarks.

And:

But there is no mistaking who is in charge here. It is Mr. Xi who is assuming the mantle of Rakhmetov — the “extraordinary man,” the agent of history — and believes his iron will and visionary leadership will deliver the world from American turbulence.

The American scholar Gary Saul Morson, the leading expert on Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, writes in his latest book about the mindset of the Russian revolutionaries, their minds transformed in the mode recommended by Chernyshevsky:

Westerners often refute an opponent’s defense of his actions by asking: what if the shoe were on the other foot? If the other party had done the same thing and offered the same defense, would you accept it? However natural this question might seem to us, many Russian revolutionaries not only dismissed it, but even, at times, seemed not to grasp it.

It is terrifying — literally, terrifying — to imagine that in Xi Jinping, we face an enemy who lionizes Chernyshevsky, and his anti-human fanaticism. Of course I don’t know for sure if these drones are Chinese. If they are, it seems to my mind — a Western mind — to be an insane provocation. Why on earth would the Chinese government do such a reckless thing? But if you realize that Xi is guided by the same novel that inspired Lenin and his merciless band, it makes more sense.

Why should we take Xi’s admiration for that wicked novel so seriously?

You regular readers will know how moved I was, and am, by the scene in Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev in which the shade of Theophanes appears to Andrei, broken and despairing in the sacked and smoking cathedral, and tells him that his destiny is to use his artistic gift to create Beauty — in his case, beautiful icons that, in the Russian Orthodox tradition, provide a window onto divine truth, onto ultimate reality — and in so doing, give hope to the suffering Russian people. The idea is that the artist has prophetic powers, the ability to perceive Ultimate Reality.

In this 2019 essay, Gary Saul Morson says the Russians are the only people on the face of the earth who revere art in this way — specifically, the art of literature. He writes:

We usually assume that literature exists to depict life, but Russians often speak as if life exists to provide material for literature. Russians, of course, excel in ballet, chess, theater, and mathematics. They invented the periodic table and non-Euclidian geometry. Nevertheless, for Russians literature is in a class by itself. The very phrase “Russian literature” carries a sacramental aura. The closest analogy may be the status of the Bible for ancient Hebrews when it was still possible to add books to it.

More:

If Americans want the truth about a historical period, we turn to historians, not novelists, but in Russia it is novelists who are presumed to have a deeper understanding. Tolstoy’s War and Peace contradicted existing evidence, but for over a century now it is his version that has been taken as correct. The reason is that great writers, like prophets, see into the essence of things. And so Solzhenitsyn undertook to reach a proper understanding of the Russian Revolution by writing a series of novels about it, The Red Wheel. He made extensive use of archives, as any historian would, and his representation of historical events never contradicts the documents. His fictional characters are often based on real people and are always historically plausible. From a Russian perspective, he expressed what even the best of historians could not: the truth. In his view, postmodern, relativist denial of truth betrayed the whole Russian literary tradition.

Solzhenitsyn claimed in his Nobel Prize speech: “Writers . . . can vanquish lies! In the struggle against lies, art has always won and always will. . . . Lies can stand up against much in the world but not against art. . . . One word of truth outweighs the world [according to the Russian proverb].” Proclaimed by a writer who survived seven years in the Gulag, such statements were not mere rhetoric, as they would be if uttered by an American writer—that is, if an American writer could do so with a straight face. They derive from a tradition in which great writers enjoy an almost mystical access to truth and bear the enormous responsibility of using their gift to discover and express it.

More:

The very intellectuals who had once defended Solzhenitsyn condemned him when they discovered he did not share some of their views. They could not entertain the possibility that they had something to learn from a very different set of experiences. No, no, it was only his experience that was eccentric, while theirs reflected the way things really are! Foolishly, this survivor of Communist slave labor camps revealed himself “to be an enemy of socialism.” Solzhenitsyn recalls a Canadian TV commentator who “lectured me that I presumed to judge the experience of the world from the viewpoint of my own limited Soviet and prison-camp experience. Indeed, how true! Life and death, imprisonment and hunger, the cultivation of the soul despite the captivity of the body: how very limited that is compared to the bright world of political parties, yesterday’s numbers on the stock exchange, amusements without end, and exotic foreign travel!”

What most disturbed Solzhenitsyn was a “surprising uniformity of opinion” that life was about individual happiness—what else could it be about?—and that it was somehow impolite to refer without irony to “evil.” Still worse, Solzhenitsyn traced this trivializing of human existence to “the notion that man is the center of all that exists, and that there is no Higher Power above him. And these roots of irreligious humanism are common to the current Western world and to Communism, and that is what has led the Western intelligentsia to such strong and dogged sympathy for Communism.” After the Gulag, such ostensibly sophisticated sympathy seemed at best the most hopeless naïveté.

Another passage:

Solzhenitsyn often cites the memoirs of the revolutionary R. V. Ivanov-Razumnk, who compared his imprisonment under tsars and Soviets. Under the tsars, interrogation never involved torture, while under the Soviets it was routine. The tsars never thought of arresting relatives of criminals: Lenin remained free and was accepted to higher education although his brother had been hanged for his role in a conspiracy to murder Tsar Alexander III. The Soviets built camps for “the wives of the accused,” and “member of the family of a traitor to the motherland” became a criminal category. In some periods, the children of these traitors were put in orphanages, where most died, while in others they were simply executed. The tsars never conducted arrests at random, but Stalin issued quotas for each district, and Lenin explicitly called for the arbitrary execution of innocent people, since killing the innocent, he explained, would create a terrorized, therefore submissive, population.

Solzhenitsyn’s comment about “the tears of Tolstoy” exhibits the peculiar irony with which Gulag is narrated. Indeed, the book’s closest literary relative is probably Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, which is also a masterpiece of history as irony. But even Gibbon never produced passages as savage as this one:

If the intellectuals in the plays of Chekhov who spent all their time guessing what would happen in twenty, thirty, or forty years had been told that in forty years interrogation by torture would be practiced in Russia; that prisoners would have their skulls squeezed within iron rings; that a human being would be lowered into an acid bath; that they would be trussed up naked to be bitten by ants and bedbugs; that a ramrod heated over a primus stove would be thrust up their anal canal (the “secret brand”); that a man’s genitals would be slowly crushed beneath the toe of a jackboot; and that, in the luckiest possible circumstances, prisoners would be tortured by being kept from sleeping for a week, by thirst, and by being beaten to a bloody pulp, not one of Chekhov’s plays would have gotten to its end because all the heroes would have gone off to insane asylums.

This is what people who give themselves over to the mindset glorified by Chernyshevsky are capable of doing. Utopian political revolutionaries and religious fanatics — for example, Islamic jihadists — think this way. They do not see the world as you and I do. Morson once again:

Compared to Soviet interrogators, Solzhenitsyn observes, the villains of Shakespeare, Schiller, and Dickens seem “somewhat farcical and clumsy to our contemporary perception.” The problem is, these villains recognize themselves as evil, and say to themselves, I cannot live unless I do evil. But that is not at all the way things are, Solzhenitsyn explains: “To do evil a human being must first of all believe that what he’s doing is good, or else that it’s a well-considered act in conformity with natural law. . . . it is in the nature of a human being to seek a justification for his actions.”

Why is it, Solzhenitsyn asks, that Macbeth, Iago, and other Shakespearean evildoers stopped short at a dozen corpses, while Lenin and Stalin did in millions? The answer is that Macbeth and Iago “had no ideology.” Ideology makes the killer and torturer an agent of good, “so that he won’t hear reproaches and curses but will receive praise and honors.” Ideology never achieved such power and scale before the twentieth century.

Anyone can succumb to ideology. All it takes is a sense of one’s own moral superiority for being on the right side; a theory that purports to explain everything; and—this is crucial—a principled refusal to see things from the point of view of one’s opponents or victims, lest one be tainted by their evil viewpoint.

If we remember that totalitarians and terrorists think of themselves as warriors for justice, we can appreciate how good people can join them. Lev Kopelev, the model for Solzhenitsyn’s character Rubin, describes how, as a young man, he went to the countryside to help enforce the collectivization of agriculture. Bolshevik policy included the enforced starvation of several million peasants, and Kopelev describes how he was able to take morsels of food “from women and children with distended bellies, turning blue, still breathing but with vacant, lifeless eyes,” in the ardent conviction that he was building socialism. Other memoirs of this period also describe how a loyal communist at last awoke to what he (or she) did. In this way, the Soviet experience inspired a rebirth of conversion literature, and Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag, which details his own change from Bolshevik to Christian, is a prime example.

By his own words in the BRICS speech, Xi Jinping extols the virtues of being a steel-hardened warrior for his idea of justice. If you read the Morson essay — and I beg you to do so! — you will understand why our own woke, though they may be pale imitations of their Bolshevik antecedents, cannot be reasoned with, only defeated. They believe that they are on the side of Truth and Justice, and that mercy and humane limits are vices that sap one’s ability to pursue the right ordering of the world by crushing those who belong to the Evil side — white people, homophobes, Christians, the rich, you name it.

Citing Solzhenitsyn’s most famous line, Morson says:

We are never closer to evil than when we think that the line between good and evil passes between groups and not through each human heart.

The key lesson here, says Morson, is that Bolshevik cruelty is inevitably the product of atheism and materialism. More:

Bolshevik ethics explicitly began and ended with atheism. Only someone who rejected all religious or quasi-religious morals could be a Bolshevik because, as Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, and other Bolshevik leaders insisted, the only standard of right and wrong was success for the Party. The bourgeoisie falsely claim we have no ethics, Lenin explained in a 1920 speech. But what we reject is any ethics based on God’s commandments or anything resembling them, such as abstract principles, timeless values, universal human rights, or any tenet of philosophical idealism. For a true materialist, Lenin maintained, there can be no Kantian categorical imperative to regard others only as ends, not as means. By the same token, the materialist does not acknowledge the supposed sanctity of human life. All such notions, Lenin insisted, are “based on extra human and extra class concepts” and so are simply religion in disguise. “That is why we say that to us there is no such thing as a morality that stands outside human society; that is a fraud. To us morality is subordinated to the interests of the proletariat’s class struggle,” which means to the Party. Aron Solts, known as “the conscience of the Party,” explained: “We . . . can say openly and frankly: yes, we hold in prison those who interfere with the establishment of our order, and we do not stop before other such actions because we do not believe in the existence of abstractly unethical actions.”

More:

Thinking novelistically, Solzhenitsyn asks: how well does morality without God pass the test of Soviet experience? Every camp prisoner sooner or later faced a choice: whether or not to resolve to survive at any price. Do you take the food or shoes of a weaker prisoner? “This is the great fork of camp life. From this point the roads go to the right and to the left. . . . If you go to the right—you lose your life; and if you go to the left—you lose your conscience.” Memoirist after memoirist, including atheists like Evgeniya Ginzburg, report that those who denied anything beyond the material world were the first to choose survival. They may have insisted that high moral ideals do not require belief in God, but when it came down to it, morals grounded in nothing but one’s own conviction and reasoning, however cogent, proved woefully inadequate under experiential, rather than logical, pressure. In Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales—I regard these stories, which first became known in the late 1960s, as the greatest since Chekhov—a narrator observes: “The intellectual becomes a coward, and his own brain provides a ‘justification’ of his own actions. He can persuade himself of anything” as needed.

Among Gulag memoirists, even the atheists acknowledge that the only people who did not succumb morally were the believers. Which religion they professed did not seem to matter. Ginzburg describes how a group of semi-literate believers refused to go out to work on Easter Sunday. In the Siberian cold, they were made to stand barefoot on an ice-covered pond, where they continued to chant their prayers. Later that night, the rest of us argued about the believers’ behavior. “Was this fanaticism, or fortitude in defense of the rights of conscience? Were we to admire or regard them as mad? And, most troubling of all, should we have had the courage to act as they did?” The recognition that they would not would often transform people into believers.

In this, we see why all the Christians of the Soviet world that I interviewed for Live Not By Lies said that the most important quality that we must cultivate in ourselves, as Christians, is the willingness to suffer for the truth. If we are not willing to pay the price, in suffering, even death, to witness to what we hold to be sacred and inviolable, then we will capitulate. If we are not willing to stand barefoot on an ice-covered pond, in whatever form that pond presents itself to us, in our own circumstances, then we will surrender to Evil.

Please read the entire Morson essay. It’s important.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rod Dreher's Diary to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.