Why Does God Show Us Evil?

On learning from history, and the teleological suspension of the logical

History is a pyramid of efforts and errors; yet at times it is the Holy Mountain on which God holds judgment over the nations. Few are privileged to discern God’s judgment in history. But all may be guided by the words of the Baal Shem: If a man has beheld evil, he may know that it was shown to him in order that he learn his own guilt and repent; for what is shown to him is also within him.

— Abraham Joshua Heschel

Heschel wrote that in the opening passage of an essay exploring the meaning of World War II. What do you think it could mean for us, if we take it as part of the key to understanding our own time?

The first thing that comes to my mind when I think of that line is the fall of the Twin Towers on 9/11. As people who have read my work for some time know, I was present to witness that. My wife and I lived in New York City then. I stood on the Manhattan side of the Brooklyn Bridge, rushing towards downtown to cover the story for the New York Post, when the first tower collapsed. It sounded like a Niagara of glass. We have all read about how one’s knees go weak in a moment of great shock — well, mine did. It was as if electrified clamps seized them from behind. How I remained standing, I don’t know.

I ambled back across the bridge, to my home in Brooklyn. My wife thought I might be dead, because I didn’t answer my mobile phone (few phones worked that morning). Mine finally rang in my pocket as I was only steps away from our apartment on Hicks Street, on the Brooklyn waterfront. My wife screamed, then ran out of the house, carrying our toddler son in her arms. I had a dusting of ash on me. I had no idea why she was so upset. I was in shock, but didn’t know what shock was at the time.

By the time the summer of 2002 came, my wife was fed up with my anger. Not only was I filled with rage at the hijackers, but the Catholic sex abuse scandal had broken nationally in January, in the Geoghan trial in Boston. A Catholic at the time, I was consumed by anger at the abuser priests and the bishops who abetted their crimes. You’ve got to get help, my wife ordered. So I went to a therapist in Manhattan.

At the conclusion of the first session, he said to me, “You will come to understand that under the right circumstances, that could have been you piloting one of those planes that hit the Trade Center.” What an insulting thing to say! I didn’t believe him. It wasn’t long before we broke off our relationship, for unrelated reasons, but I thought the man was saying some stupid thing that therapists are supposed to say.

In time, I would come to see that he was right. There’s no point in retelling the story of how I came to passionately support the Iraq War, believing with all my heart and mind that it was the right thing to do, the courageous thing, the thing that we had to do to keep faith with the dead of 9/11. It took several years for me to see that I had been wrong, and so had our country. In fact, I had supported an act by our government and our armed forces that was motivated by reasons not so far from the ones that drove Mohammed Atta and his confederates to fly airliners into buildings: those having to do with the righteousness of our cause. It didn’t matter that innocent people would die, as long as the symbols of the Enemy that had caused our people pain and humiliation were crushed.

I want you to hurt like I do sang Randy Newman, in a bitter ballad about a divorce. Honest I do. That’s how I felt about the Arab Muslim world in 2002. Of course, that’s how many of them felt about us before 9/11.

There was no chance in the world that in the autumn of 2001, I would have seen the towers fall and thought, ah-ha! this was a sign to us that we should behold the evil capacities inside ourselves, and repent. Would anybody? Yet I can’t deny that this was one of the historical lessons of 9/11 and the Iraq War. This is a hard thing to wrap one’s mind around, even today. That fall, I went with a small media contingent down to Ground Zero, to hear President Bush give a speech. The enormity of what had been done there was hard to describe. Staring out at the vastness of the site, with mountains of twisted metal piled high, and not a straight line anywhere — it was a vision of hell. And hell is exactly what I wanted the president to deliver to the people who caused it: Arab Muslims. The details — the logic, the facts — did not matter.

We often create stories that justify what we want to believe in our hearts, and impose those stories on the world. Sometimes those stories take the form of ideologies. In 2003, the writer Paul Berman published in The New York Times a long piece about Sayyid Qutb, the ideological godfather of modern Islamic terrorism. This paragraph has stayed with me all these years:

Qutb is not shallow. Qutb is deep. ''In the Shade of the Qur'an'' is, in its fashion, a masterwork. Al Qaeda and its sister organizations are not merely popular, wealthy, global, well connected and institutionally sophisticated. These groups stand on a set of ideas too, and some of those ideas may be pathological, which is an old story in modern politics; yet even so, the ideas are powerful. We should have known that, of course. But we should have known many things.

Berman goes on to summarize Qutb’s ideology, which grew out of his Islamic radicalism and his analysis of alienation and social injustice in the modern world:

Europe's scientific and technical achievements allowed the Europeans to dominate the world. And the Europeans inflicted their ''hideous schizophrenia'' on peoples and cultures in every corner of the globe. That was the origin of modern misery -- the anxiety in contemporary society, the sense of drift, the purposelessness, the craving for false pleasures. The crisis of modern life was felt by every thinking person in the Christian West. But then again, Europe's leadership of mankind inflicted that crisis on every thinking person in the Muslim world as well. Here Qutb was on to something original. The Christians of the West underwent the crisis of modern life as a consequence, he thought, of their own theological tradition -- a result of nearly 2,000 years of ecclesiastical error. But in Qutb's account, the Muslims had to undergo that same experience because it had been imposed on them by Christians from abroad, which could only make the experience doubly painful -- an alienation that was also a humiliation.

That was Qutb's analysis. In writing about modern life, he put his finger on something that every thinking person can recognize, if only vaguely -- the feeling that human nature and modern life are somehow at odds. But Qutb evoked this feeling in a specifically Muslim fashion. It is easy to imagine that, in expounding on these themes back in the 1950's and 60's, Qutb had already identified the kind of personal agony that Mohamed Atta and the suicide warriors of Sept. 11 must have experienced in our own time. It was the agony of inhabiting a modern world of liberal ideas and achievements while feeling that true life exists somewhere else. It was the agony of walking down a modern sidewalk while dreaming of a different universe altogether, located in the Koranic past -- the agony of being pulled this way and that. The present, the past. The secular, the sacred. The freely chosen, the religiously mandated -- a life of confusion unto madness brought on, Qutb ventured, by Christian error.

Sitting in a wretched Egyptian prison, surrounded by criminals and composing his Koranic commentaries with Nasser's speeches blaring in the background on the infuriating tape recorder, Qutb knew whom to blame. He blamed the early Christians. He blamed Christianity's modern legacy, which was the liberal idea that religion should stay in one corner and secular life in another corner. He blamed the Jews. In his interpretation, the Jews had shown themselves to be eternally ungrateful to God. Early in their history, during their Egyptian captivity (Qutb thought he knew a thing or two about Egyptian captivity), the Jews acquired a slavish character, he believed. As a result they became craven and unprincipled when powerless, and vicious and arrogant when powerful. And these traits were eternal. The Jews occupy huge portions of Qutb's Koranic commentary -- their perfidy, greed, hatefulness, diabolical impulses, never-ending conspiracies and plots against Muhammad and Islam. Qutb was relentless on these themes. He looked on Zionism as part of the eternal campaign by the Jews to destroy Islam.

And Qutb blamed one other party. He blamed the Muslims who had gone along with Christianity's errors -- the treacherous Muslims who had inflicted Christianity's ''schizophrenia'' on the world of Islam. And, because he was willing to blame, Qutb was able to recommend a course of action too -- a revolutionary program that was going to relieve the psychological pressure of modern life and was going to put man at ease with the natural world and with God.

This Berman essay led me to read more about Qutb and his thought, because I wanted to understand why people like the hijackers could justify doing what they did. It turns out that Qutb really did make a lot of sense. Don’t get me wrong: his philosophy is bloodthirsty and totalitarian. But its internal logic is powerful. Read his little book Milestones if you want to know more. It is exactly the sort of thing that would light up the mind of an intelligent and restless young Arab man stuck in a world of hopelessness, and looking for something that helps him understand his rage, and direct it. Qutb identifies the source of their humiliation, and of the world’s disorder, and proposes a clean remedy (global holy war to establish Allah’s utopian kingdom on earth).

Just over a year ago, when I was in Moscow, at dinner with a Russian family, I said that I didn’t understand how anybody in pre-revolutionary Russia believed what the Bolsheviks were preaching. The father, sitting at the head of the table, told me a long story of the brutality and cruelty of the Tsarist regime, abetted by Orthodox Church authorities, going back to the 17th century, up until the dawn of the 20th. My interlocutor was himself an Orthodox Christian, and no supporter of Bolshevism. But he wanted me to know that it came from somewhere.

I say all this in light of Rabbi Heschel’s lines because today, we are in a period of great confusion and passion. People with elaborate theories that explain the world, and tell us what we have to do to order it rightly, find receptive audiences. Who is going to be our Sayyid Qutb? We are making ourselves ready for him. Hannah Arendt said that a clear sign of a pre-totalitarian society is one in which people quit caring about discerning truth, and instead believe anything that feels right to them, and confirms their prejudices. If you cannot recognize this habit of mind ubiquitous in America today, you aren’t paying attention. It’s not just Them; it’s Us too. I published earlier this fall a book that draws out how certain influential people on the Left are doing this in the name of “social justice,” but the behavior of many people on the Right, in the aftermath of the election, has shown that we are often no better.

What is clear to me is that we are living in an advanced way the result of narrative collapse, Douglas Rushkoff’s term for the loss of belief in the controlling stories by which we organize our common life, and find meaning. Alasdair MacIntyre saw this happening decades ago, and predicted that we would end up with exactly the kind of chaotic mess we have today. There have been times when our lives have been more chaotic, but thanks to technology, it’s hard to think of a previous time when we had no broadly agreed-upon framework with which to make sense of events, and debate what to do. We see this on the Left and the Right alike: people full of passionate intensity, who find self-criticism or self-doubt to be a sign of moral weakness. I’ve seen it and heard it among so many people on both sides. I am watching good men and women destroy themselves by embracing hysterical ideologies — again, on both Left and Right — that are simplistic, moralistic, and unfalsifiable.

It’s the unfalsifiable part that’s so scary. I had a tense discussion just the other day with a friend who insists that the presidential election was stolen. I told my friend that I happen to know personally the Trump-appointed federal judge who wrote the ruling shooting down the president’s claims in Pennsylvania. He is a deeply conservative, profoundly religious man — and if he says there was no case there, then I believe it. My friend said no, that she believes the election was stolen. Give me one reason why you believe that? I asked. She said, “I just believe it.”

If you’re on the other side of the Trump election tale, you might wince at that, or laugh at that. But I have had arguments with friends on the Left about other controversial issues that are just as unfalsifiable to them. I wouldn’t call this evil, but I would call it a willful abandonment of cognitive responsibility — or, to steal a Kierkegaardian phrase, a teleological suspension of the logical. That is to say: anything that stands in the way of achieving the outcome we desire must be rejected.

What’s new is how naked and unadorned it all is today. But look: I see in these people — among whom I count friends — a version of myself in 2002. I had seen evil on 9/11, and because I knew without a shadow of a doubt that I could never be like the evildoers on 9/11, I endorsed a related evil. I cannot guarantee that I won’t make the same mistake in the future, but I have earnestly tried to repent of it, and to recognize that the capacity for the teleological suspension of the logical is always within me. And everyone. Solzhenitsyn warned readers of The Gulag Archipelago that they should not live under the illusion that what happened in Russia couldn’t happen in their country. But right now, we are seeing the same kind of utopian thinking rise again, thanks to smart people who are bound and determined to ignore the lessons of history, and gullible young people who never learned the history at all. All the evils we have seen in just the history still within the memory of living people — all of it is within ourselves.

Kierkegaard said the problem is that life must be lived forward, but can only be understood backwards. What is clear in 2020 was not so clear in 2002, at least not to 35-year-old me, traumatized by the sights, sounds, and smells of 9/11. (Ever smelled burning human flesh? I have; it’s sweet.) Maybe these things were clear to older people back then, people who had seen history, and understood it, and were wary of rushing to judgment and action. But I wouldn’t have listened to them, and I know many others wouldn’t have either. Anyway, it is a complicating truth that to remain paralyzed by neutrality, unable to make a choice for fear of making the wrong one, really can be a kind of moral cowardice.

Heschel was not in favor of neutrality, certainly. He lost most of his family in the Holocaust. He knew well the wrongness of refusing to choose righteousness in a crisis. He wrote that “a frantic call to chaos shrieks in our blood,” and asked, “How are we going to keep the demonic forces under control?”

This is the decision which we have to make: whether our life is to be a pursuit of pleasure of an engagement for service. The world cannot remain a vacuum. Unless we make it an altar to God, it is invaded by demons. This is no time for neutrality.

True enough — but how can we know that we are making the world an altar to God, and not to the demons? I don’t believe that the men who led the United States into that awful war, a war of choice, did so thinking they were serving demons. In fact, the rhetoric President Bush used to justify the war was the rhetoric of righteousness, human rights, and democracy. This is actually more frightening, and more destabilizing: the idea that we could do evil, thinking we are doing good. This is the essence of tragedy, and we Americans are not a people who think in tragic terms.

I want to offer one more Heschel quote for contemplation:

We lack the power of prematurely force the advent of the end of days, but we are able to add to the sacred from the profane. And it is possible to accomplish such additions every hour. Preparation is necessary seen in commonplace matters, for you cannot reach the significant without beginning with the insignificant. The same heavens that are stretched out over the ocean also cover the dust on an abandoned path. And though the destruction of evil and the eradication of malice are not easy tasks, laving one’s hands before eating bread and reciting the blessing over the bread are not to be trampled upon and made light of.

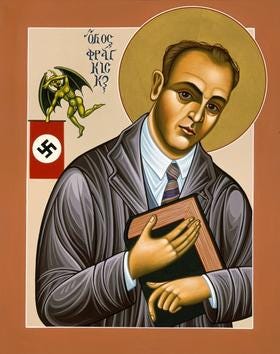

I think of Franz Jägerstätter and his family, whose story was told earlier this year by Terrence Malick in the film A Hidden Life. They were Austrian Catholics who lived in an Alpine farm village. When Nazism emerged, and came to their town, most of their neighbors embraced it. They thought they were doing good: being patriotic, showing solidarity, standing for restoring justice to greater Germany, done so badly by the Treaty of Versailles. But the Jägerstätters knew better. Why? Because they lived disciplined lives as faithful Catholics, and sharpened their moral perception such that they could see that the devil had come to their village as an angel of light.

It was the little things that helped the Jägerstätters to resist the madness around them, even to death (Franz was executed in prison because he refused to swear an oath of allegiance to Hitler; he has been beatified by the Catholic Church, and is on his way to sainthood.) Maybe the thing for us to do, in the face of the destructive passions of this hour, lost in the fog of information and insult, is to redouble our efforts to draw out the sacred from the profane in our own lives, with the things we do understand more clearly, and can control. The heroism and holiness of Franz Jägerstätter’s prison sacrifice in 1943 began with the simple saying of his rosary beads by candlelight in the silence of his mountainside cottage. If we are faithful and disciplined in small things, maybe it will make us less susceptible to fall for the big lies.

I have had a wonderful response to last night’s meditation on Roscoe, my old and expiring dog. From the mailbag:

We had to put our dog Bailey (Bailey's Irish Cream) to sleep on Friday. Heartbreaking. We'd had her for 13 years, and she was 1 or 2 when we got her. 15 years is a long time for a hound to live.

The strangest part is that she got very sick last year at Thanksgiving, so we took her to the vet on Friday, the day after Thanksgiving 2019. The vet found a large tumor in Bailey's chest and told us we could put her to sleep right then or take her home, see how she did for the next few hours, and come back when we needed to. Well, we got home, and Bailey slowly started feeling better. She honestly did pretty well until about three weeks ago when she really started slowing down on her eating. On Thankgiving this year, she just kept getting weaker and weaker. My wife and I were up with her on and off all night, and we knew we were at the end.

The most difficult part for me is going home from work every evening. No little dog comes to greet me at the door. Man, I miss that stubborn old hound!

I worked from home for 10 years, and I dreaded Bailey dying for most of it. I knew I simply had to enjoy the time I had with her. Sounds like you're doing that with Roscoe. Clearly, he's stolen your heart much like Bailey had stolen mine.

When the time comes, you might see if there is a pet hospice that will come to your house to put him to sleep. I didn't even know there was such a thing. But a very nice vet came to our apartment and took care of everything. Bailey hated going to the vet -- as soon as she would smell that we were at the clinic, she would get terrified. I'm very glad we didn't have to put her through that at the end.

Here is Bailey, of blessed memory:

Another reader:

I so know what you're going through with Roscoe. I'm an "equal opportunity" pet lover between dogs and cats; my husband is more of a dog person and has had a dog nearly all his life. Our current pooch is a rescue animal, an American Bull Terrier (aka "pit bull"), which I did not want, but who overcame my reticence about her breed with her sweetness. When we took her to the vet for her first visit, our vet told us she was never hesitant to enter the exam room to see a pittie - the vast majority are love sponges; the only dogs who ever bit her during her +40 years of practice were Chihuahuas. My husband says he loves our dog so much it hurts his heart.

Animals don't philosophize, they just love us. I believe they know something's going on with them, but I think an aspect of God's mercy in creating their natures is that they're not anxious about dying per se. Our pets are pretty wise when nearing death, even as they truly do not wish to be parted from us. My cats have generally wanted to crawl underneath something so they aren't set upon as prey, but my last cat was too weak for that. Her poor little body was past done, but her spirit put a lid on any physical distress and just wouldn't let go of us; we finally had to put her down. She's the only pet we have ever buried in our yard, and I read the Vesperal Psalm (How magnified are Thy works, O Lord; in wisdom hast thou made them all) over her grave through tears. It was much the same with the first dog my husband and I had as a married couple; for days she couldn't get herself outside and didn't want to eat anyway, but held on a long time until the last trip to the vet. Most of our pets have died at home, without much pain and during the night. Last year we went to Arizona to visit my mother-in-law for Christmas. She told us her dog wasn't doing well, and when we arrived I knew she was at death's door, but I also know MIL had told her we were coming, and she held on in order to greet us with a wag of her beautiful Golden Retriever tail. I traced a cross on her forehead. She died that night.

There is definitely a pall over you as you wait for the inevitable. And then when it happens, what do you do? You grieve, for as long as it takes, just as for a human friend. In a very real sense, we have loved our pet into life; we know each other and each other's uniqueness in a kind of communion. Paradise would not be Paradise without our pets, and the Psalmist said that God does not withhold any good thing from those who love Him. There's no doubt in my mind or heart that we will have them all around us again in the Age to Come; God is just that good. (Hieromonk Tryphon on Vashon Island also thinks this will be so.) And then, after some time has passed - even if you think there could never be another dog like Roscoe (and you'd be right) - you might be ready to love one again.

All shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well. Roscoe is in our Lord's care, too.

What comforting words! Thank you. From another reader:

My wife made me get a toy poodle and promised to take care of it. Ha! That dog was MINE from the first day and we adore each other. When he looks at me so trusting and livingly and worshipful- it reminds me of how I am to love my God and my Saviour. When he tears something up and otherwise does not mind me it reminds me of how I disobey God despite my love. Yet he gives me treats anyway.

You probably don't want to hear this, and you WILL NOT want to do it, but when the dreaded day comes make yourself get another dog within a month. One of similar size that is happy with a fenced yard. It may feel disloyal, but you will be glad you did.

I think this is true. I have thought about what kind of dog to get next. I wouldn’t mind a bigger dog, in theory, but there’s nothing quite like a dog small enough to sit in your lap. I don’t care for delicate dogs. Turns out a schnoodle (schnauzer-poodle mix) like Roscoe is just about perfect for us.

Another reader writes of his dog:

Buddy was a white and buff Cocker Spaniel who nobody wanted. A neighbor who knew we liked Spaniels (at the time we had a 10-year old King Charles Cavalier) mentioned that a tenant of his had a 2-year old Cocker that she needed to find another home for and asked if we would be interested. Making a long story short, we adopted Buddy. He took to our Cavalier immediately and it was fun to see her take the role of alpha. Unfortunately, however, she was sick and died within 6-months of when Buddy joined the family. He clearly grieved for several weeks after her death.

The woman we adopted him from had been recently widowed when she bought Buddy from a pet store. For various reasons, most of which we have only guessed at, this was not a well considered purchase as she was not capable of taking care of him. Among other things, we learned was that she would regularly leave him with friends, who had several bigger dogs and at least two smaller children, during which time we believe he was tormented and possibly abused.

It turned out that Buddy had quite a bit of "baggage". He bit several people (fortunately none seriously), including my wife who was trying to take something away from him at the time. Most of our neighbors at one point or another asked us why we didn't get rid of Buddy. Frankly, at times we asked ourselves the same question. As Buddy aged, however, he mellowed considerably and became a lovable, if rascally, dog.

On Easter Sunday 2014, my wife noticed that Buddy seemed intent on eating dirt, both from our yard and potted plants in the house. The next day she took Buddy to our vet to follow-up. Our vet sent her immediately to the local urgent care pet hospital (they are fantastic...Rhode Island's version of Angel Memorial) because the vet determined Buddy had become seriously anemic, hence his dirt eating. Buddy was diagnosed with a hematolytic anemia which is prevalent in Spaniels. He was not quite 11 at the time and thus began treatments, including several medicines and two transfusions (and costing roughly $2,500.00). While we were dealing with Buddy's illness, we were also finalizing wedding plans for our older daughter who was married in early May of that year. Needless to say, our emotions were running high.

About a week after our daughter was married, it became clear that Buddy was not going to be cured and that he was suffering. My wife and I came to the painful decision that the time had come to put him to sleep and we made an appointment with the animal hospital for the next day. Our younger daughter, who had a special bond with Buddy, came from Boston to say her goodbyes. While my wife was bringing our daughter to get the train back to Boston, Buddy snatched a coffee cake off our kitchen, brought it into the living room and ate it, spreading crumbs and debris all over the place. Finding Buddy in the middle of this mess when she got home from the train station, all my wife could do was laugh. We were with him when he went to sleep (which is exactly was the process is like) peacefully the next day. We like to say that he went out in style!

Rod - At the time a woman that I had worked with for years, also a dog lover, said to me that when you see a man standing in the parking lot of a Veterinarian's office crying, you can be sure what just happened. You and your wife will know "when it is time".

What an image. I get it. I really get it.

One more, something that just came in:

God's created purpose for Man is to tend to the garden and his beautiful Creation. The dominion over Creation that God delegated to Man is one of humble servitude to be His sinless creatures' stewards. God bless you for doing it well. Someday, after Roscoe goes to Jesus, another sinless creature will come to you to be your next best friend. And when the day comes when you go to Jesus, all of your lifetime's companions will be waiting for you, there, in your field from the Lord.

May it be so.