That is a detail from a canvas by Francisco Goya, titled, “The Drowning Dog.” Here is the entire painting:

“Drowning Dog” hangs on the wall of the Prado Museum in Madrid. I spent a few hours there on Friday — my first visit to that great institution — and though I beheld many masterpieces, it was this simple image that pierced my heart and lodged itself in my imagination such that days later, I can’t stop thinking about it. It hangs in a special room dedicated to Goya’s “Black Paintings,” a series of canvases he painted during a period of great torment in his life, when he struggled with madness and despair, in part because of all the horror he had seen in Spain’s Napoleonic wars. Goya painted them on the walls of the rental house in which he was living; the owner later had them removed, and they ended up at the Prado. The best known of these Black Paintings is “Saturn Devouring His Son”; I’d say “Drowning Dog” is the least bleak.

What is so captivating about that image? Mind you, I had been going through the museum seeing so many deeply moving paintings on religious themes, and even praying before some of them. And then I got to “Drowning Dog,” and I stopped me cold. My first thought: “That is my interior life since 2012, when it all fell apart.”

It really is. That poor little creature, struggling to keep his head above water, with the void above him. His eyes, wide and hopeful; maybe someone will save him. But we see no one there, only absence. Meanwhile, here comes another wave.

This is the human condition, is it not? I shared that with a Christian friend, and told him that I have never encountered an articulation of my inner life over the last dozen years as acute as this. He texted back to ask: What about those epiphanies of enchantment you’ve had, like the Holy Fire in Jerusalem? A good and reasonable question!

I told him those epiphanies in which God revealed something of Himself tell me that I will not drown, and that my struggle against the water and the waves has ultimate meaning. There is no void there. But what they don’t do is pull me out of the water. I may be desperately dogpaddling for the rest of my life — like most people have to do.

See, this is what I mean by enchantment: not deliverance from our suffering, but the assurance that we do not suffer alone, and our suffering is not in vain. The little dog looks up and sees the void, but the enchanted Christian knows there is no void, ultimately. The poor child in North Carolina, Micah Drye, drowned in the flood calling on Jesus to save him. Why did Jesus not save him after all? None of us can know. His grieving mother heard his call as he was swept away, and says today that she is so comforted that he called not on her, but on Christ. This is the way.

I can easily understand someone reacting angrily, and citing this as an example of how God must not exist, because He would have saved that child if so. This is the issue dealt with in the Book of Job. God tells Job that he cannot possibly fathom how reality works. I have thought for a long time about theodicy (the area of thought devoted to exploring how an all-good, all-powerful God can allow evil), and really, I’ve come up with nothing better than that.

On the day my sister was diagnosed with terminal cancer, I lay in her bed at her home, sharing it with her youngest child while she and her husband were in the hospital, crying for her, and begging God to save her life. In The Little Way of Ruthie Leming, I wrote about lying there becoming aware that hovering above me was a presence, and the presence communicated to me that Ruthie was not going to survive this, but that I should be at peace, because this had to happen. If not for the gift of faith in that message, the pain and injustice of her passing would have been too much to bear.

So, Goya’s drowning dog. To me, this is a symbol of hope, because it is a symbol of truth. This is how it is for us. Look at the little dog’s eyes:

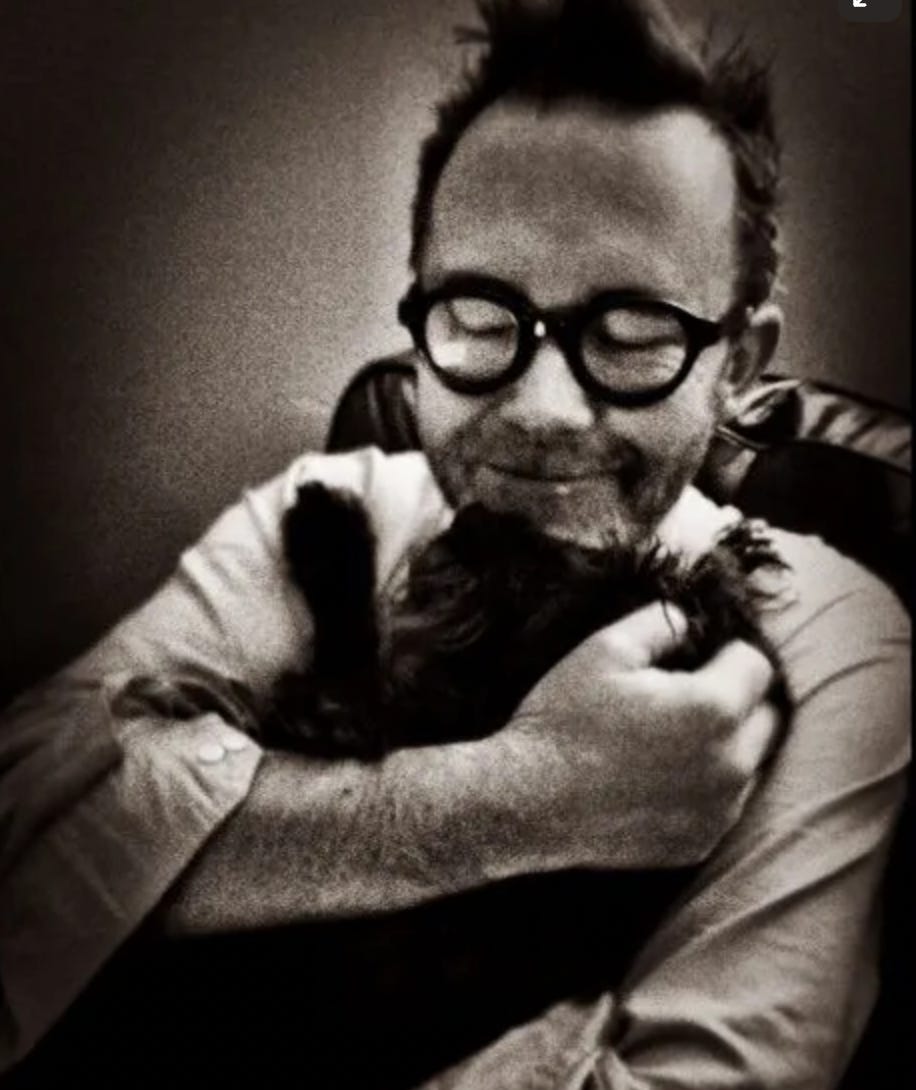

How is it that Goya, with just a few strokes of a brush, can convey such pathos? Goya’s dog looks a lot like my beloved Roscoe, the dearest friend I’ll ever have. Hell, man, I’m sitting here crying now, just thinking about him, and how much his loved kept me going through the blackness of many years. As I wrote when he died:

I sometimes had a contemplative attitude towards Roscoe. He would be in my arms on an ordinary night, staring up at me with his chestnut-colored eyes, with the purest love. It was eerie; the kids noticed too. It was utter adoration. The feeling was mutual. There was nothing complicated about Roscoe’s love. In a family suffering a prolonged crisis that nobody could talk about but everybody sensed at some level, Roscoe was the still point in a disintegrating world. I would hold him, and watch him as he slept, and silently thank the Lord for sending him into my life. Into our lives. I needed him far, far more than he ever needed me. Knowing that this awful day was coming one day only made my love for him more intense.

… [T]he memory of this little dog, and what he meant to me, will be with me until I draw my last breath. He changed me. He made me a better man. Never before did I care much for dogs. Now I regard them as a sign that God loves us. Here we are below on the last time we saw each other. Once we were so close that he knew I was coming home long before my car drew near (Julie and the kids saw this happen many times). When we returned as a family after a month in Paris in 2012, he was ecstatic, and leaped into my arms. But last fall, Roscoe was no Argos: by then, he was lost in the fog of old age, already having lived past the allotted time for his breed, and no longer recognized his master. I grieved this, but I dared not let the feeling take hold of me. Had to be brave. Besides, had I broken down on the front porch of what used to be my house, there would have been nobody to comfort me.

He may have been gone already then, but on so many agonizing loveless nights over the past ten years, Roscoe was there for me, reminding me that there was at least one thing in this world I would never lose: my dog’s love.

Below, Roscoe and me on the night we returned from Paris after a month. Oh sweet Jesus, how I loved my little friend. Looking back, Paris was the last happiness my wife and I had. I could tell something had changed in her that month, but I didn’t know what. I did not know it when this photo was made, but holding Roscoe close to my heart would be one big way I would endure the next ten years without collapsing:

When we found him, Roscoe was drowning, sort of, as a puppy, beaten by his owner, and lost in a park. We saved him. And then he saved us — or at least saved me by accompanying me with love through those black years of abandonment, when I begged the Lord, through hot tears, to fix my marriage, but He did not. Life is a struggle to keep our head above water and waves — a struggle that we cannot win, ultimately. But how we struggle is everything. If we can struggle buoyed by faith that tells us God sees us, and that our struggle has ultimate meaning, then we can bear it.

In Living In Wonder, I quote the great psychotherapist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl saying that if a man knows his suffering has meaning, he can endure it. Dr. Frankl built an entire school of psychotherapy around this insight. I think of my friend Michael, a wreck of a man when I met him in New York City in 2001. He was probably in his early 60s, but looked much older. He had been a drunk for most of his life, and a very promiscuous homosexual who slept with gay priests. The trajectory of his life was set when, as a boy, he was raped by the principal of his Catholic school. When he told his working-class Irish Catholic mother what monsignor had done to him that day, she slapped him hard and told him never to speak ill of the clergy. With that, Michael’s mother turned her boy over to the predations of that priest.

Michael had finally gotten clean, and repented, but he was a shell of a man when I knew him. He’s dead now, so I can tell you that he was a good source of mine into the corruption of the Archdiocese of New York, regarding priest abuse and coverup. Cardinal Egan was so angry at the scoops I was publishing, mostly because Michael knew where the bodies were buried, so to speak, and told me everything he knew, that he rang up Rupert Murdoch and asked him to take me (a New York Post columnist) off the beat. Murdoch complied. I tell you that so you will know how deeply embedded Michael was in that sordid world.

The last time I saw Michael, he was ecstatic because he had recently been to a mass in Queens celebrated by a mystical Croatian priest who claimed to see the Virgin. Michael waited at the back of the crowd to go up to receive the priest’s blessing after it was over. After he received the blessing, Michael was leaving the church when the interpreter for the priest, who spoke no English, ran after him.

“Father says the Virgin told him that she was there when you suffered so terribly as a child, and that she suffered with you. She wants you to know that,” the interpreter told Michael.

Now, you or I might have thought: Thanks, Mary, but why didn’t you stop the evil monsignor? Not Michael. He wept recalling the overwhelming relief this message brought him. He had not been alone. Heaven saw what happened. His own mother refused to believe him, and help him, but the Mother of God knew it was true, and felt his pain. For Michael, this was enough. Michael was an enchanted Christian.

For us Christians, our God is a God who suffers with us. “Compassion” means “suffering with.” Why didn’t Mary stop the evil monsignor from raping that boy? Why didn’t God spring Alexander Ogorodnikov from the Soviet prison, instead of sending angels there to assure him that his suffering had ultimate meaning (specifically, that death row prisoners to whom he witnessed for the faith had accepted Christ, and would go to heaven after their execution). We could fill libraries with similar questions, but they all come down to, Why didn’t Jesus climb down off the Cross?

There is a profound mystery here — the most profound, I think — that we cannot penetrate with our reason, but we can know through faith. Goya’s little dog is Michael, not pulled from the waters by God, but comforted to know that he does not struggle against the waves unseen. It is enough. It has to be, somehow. I can’t explain it, but I live it. I bet you do too.

There were so many other paintings of overwhelming beauty in the Prado. This one by Hieronymous Bosch — the central painting of The Triptych on the Adoration of the Magi — got to me too:

Notice the great and prosperous city in the distance, and in the middle ground, two armies rushing to battle. What none of them can see is that in the humble hut on the periphery of the life of the world, something utterly extraordinary has happened. God has come to earth incarnate as a baby boy belonging to a poor woman, indeed a virgin. Three astrologers — “kings” — came from the Near East to adore the hidden god. They brought gifts fit for royalty, and present them there in the tumbledown shed.

This is how God is: he appears hidden from the rich, the proud, the violent. This is the testimony of the Psalms. This is the testimony of Mary at the Annunciation. This painting, as I see it, reveals one of the great mysteries of our faith. The Three Kings from afar saw the truth of what happened in that cow shed, while the people who lived closest to it remained ignorant. How often do I do the same thing — walk around the city so lost in thought that I fail to see the glory of God manifesting around me? Just like the writer Gorchakov in Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia.

In the gallery near to the one where this Bosch canvas hangs, I saw a young Muslim woman, in hijab, sitting on a bench looking at a painting of the Virgin. I wanted to talk to her, to ask her what she saw. I knew how to “read” the painting — meaning, decode its symbolism — because I am a Christian. I wondered if she was puzzled by it, and could only see in it aesthetic achievement. But having just seen the Bosch triptych, I wondered if this Muslim woman, beholding these images with fresh eyes, could see something true in them that eluded the jaded eyes of we who have been raised in Christian culture. I regret not trying to talk to her.

I had never heard of the artist Daniele Crespi, but his Pietà in the Prado really got to me. Here is a detail:

Notice Mother Mary’s face:

Think of the eyes of Goya’s drowning dog. This is no dog, but the Mother of God! This is her, and this is a little dog. This is you. This is me. This is life. To be enchanted as a Christian is to know by faith that when we look to heaven for relief, that there is Someone to meet our gaze. The path that has been given to us has been walked by a God who shared our suffering, and who died in shame and agony, even feeling in a moment abandoned by his Father in heaven. But that wasn’t the end of the story for Him, nor is our suffering the end of the story for you and me.

It is a hard truth that we cannot share in His victory over death without sharing in his passion too. That’s how it works. Faith, and fortitude, keep our head above the waves.

Last night back in Budapest, I watched My Dinner With Andre (1981) with my houseguest, the philosophy professor Titus Techera, who is lodging with me until he can find a flat of his own. It had been years since either of us had seen that strange and compelling movie. This scene — I’ve transcribed Andre Gregory’s monologue below — stunned me. He’s talking about the Benedict Option!

They're feeling that there'll be these pockets of light springing up in different parts of the world and that these will be, in a way, invisible planets on this planet, and that as we, or the world, grow colder, we can take invisible space journeys to these different planets — refuel for what it is we need to do on the planet itself, and come back. And it's their feeling that there have to be centers now where people can come and reconstruct a new future for the world.

And when I was talking to Gustav Bjornstrand, he was saying that actually these centers are growing up everywhere now, and that what they're trying to do, which is what Findhorn was trying to do, and, in a way, what I was trying to do. I mean, these things can't be given names, but in a way, these are all attempts at creating a new kind of school, or a new kind of monastery.

And Bjornstrand talks about the concept of" reserves"— islands of safety where history can be remembered, and the human being can continue to function in order to maintain the species through a dark age.

In other words, we're talking about an underground, which did exist in a different way during the Dark Ages, among the mystical orders of the church. And the purpose of this underground is to find out how to preserve the light, life, the culture — how to keep things living.

You see, I keep thinking that what we need is a new language, a language of the heart, a language, as in the Polish forest, where language wasn't needed. Some kind of language between people that is a new kind of poetry.....that's the poetry of the dancing bee that tells us where the honey is.

And I think that in order to create that language you're going to have to learn how you can go through a looking glass into another kind of perception, where you have that sense of being united to all things — and suddenly you understand everything.

My Dinner With Andre is a discussion over a meal between two secular New York intellectuals who mostly talk about the wild adventures of Andre Gregory, a theatrical director, as he grappled with a midlife crisis. He speaks of going off to exotic overseas locales — the Polish forest, the Findhorn colony in northern Scotland, the Sahara, Tibet — and having strange, mystical, semi-religious experiences. Wally (Wallace Shawn), his friend, is a younger, struggling New York playwright who has a more scientific, rationalist mind. He pushes back against Andre, saying that he doesn’t understand why people need enchantment. Why can’t they do as he does, and find sufficient meaning in the everyday?

Andre’s stories — based on things that really happened to him — are indeed bizarre, but weirdly relatable, in that he was on a quest for meaning in a time in his life when he was tempted by despair. Naturally I am more sympathetic to Andre, but Wally is not wrong to insist that most people cannot afford to travel abroad in search of Ultimate Meaning, and that a solution must be found in the everyday. To me, Wally seems to be grappling with the problem of Meaning mostly by defining it out of existence. (I once interviewed Wallace Shawn in the late 1990s, and found him to be a superbly arrogant New York liberal, a man dripping with contempt for those who didn’t see the world as he did.) Nevertheless, Wally has a point. But so does Andre, however baroque and bizarre his experiences.

What they agree on is that modern man has to fight to stay in contact with Reality, and that we are in danger of becoming automatons, losing ourselves in the everyday — of turning into machines who simply exist, but don’t live. Titus and I talked long into the night over wine about all this. I told him about my favorite teacher from high school (who reads this newsletter!), and how he told me a few years after I graduated that there had been a change in the students at our school, a public school that drew gifted kids from all over the state. In the early classes (I was in the first class), most students seemed motivated by genuine curiosity about the world, and about learning. But over time, most students seemed mostly to want to know the answers so they could pass the tests, and get on with their lives of achievement. But to what end?

As I see it, the world has become ever more like the one Andre sees, and that Wally also perceives, though not as acutely: as a world without ultimate meaning. This is a horrible world, a world in which dogs drown and people suffer, without purpose. Christianity has an answer — Christianity has the Answer! — but it is ever more difficult to find it, given the civilizational breakdown, and the loss of a sense of meaning. Strangely enough, watching this eccentric movie helped me to understand better what my own mission as a writer has been: to hold out communities of faith, of real faith, as ways of keeping things living, of preserving the light in a time of overwhelming darkness.

As you will see in Living In Wonder, I ran across in my research people who went deep into the darkness of the occult as part of their search for meaning, and who escaped it — but who came back saying that they met with demonic “gods” who told them that their ultimate plan is to enslave humanity to the Machine as a way of destroying us, and defeating God’s plan. I quote at length one academic who had this experience, but since finishing the manuscript, I’ve heard of at least two others who have had precisely this experience. I went to bed last night with a strong intuition that this is the significance of my trilogy — The Benedict Option, Live Not By Lies, and now Living In Wonder: to give hope to people in this time of chaos and evil, by revealing our condition, and how to get through it. We need to understand the world in which we find ourselves, and to create countercultural communities (not necessarily intentional communities, like Findhorn, but communities all the same, embedded in the everyday world); this is The Benedict Option. And we need to be prepared to suffer for the Truth; this is Live Not By Lies. And finally, per Living In Wonder, we need to become re-enchanted, to recover what Andre says is “another kind of perception, where you have that sense of being united to all things” as the vision that will enable us to do what we must, to keep the light of hope — true hope, not false enchantment — alive in our own hearts, and in our world.

Would I have been able to write these books without being thrown into the tumult of liquid modernity, and forced to struggle against the waves? No. Maybe this is the meaning behind what has happened to me. And maybe this is the meaning behind what has happened to you, too, dear friend. But fear not: there is hope!

I was in the Prado in April and was also struck by the Drowning Dog painting. You beautifully capture the emotion and significance of that piece, both in your own life and in all of our lives as we struggle. Thank you.

Thank you as well for your writing. My first introduction to you was Crunchy Cons, and after that I would occasionally read your pieces in the American Conservative. But it wasn't until I started subscribing to your Substack that I became deeply impressed by your intellect and work. I am often moved, and often enlightened, by what you write (I appreciate the comments section too--you attract thoughtful readers and thinkers). During the past few months I have read your Dante book, Live Not By Lies, and the Benedict Option, and I'm eagerly awaiting your new book.

I just want to send you my sincere gratitude for helping bear a torch of faith and love and wisdom in these troubling times. There's a line I read somewhere--can't remember the source--that was something like, "He has not returned from hell empty-handed." You haven't either.

In Eden, Adam named all the animals, so it is implied that they did not fear him. In Heaven, and in the reconstituted world, animals will not fear humanity, either. In our Fallen World, they do, and this is a good thing, as it helps them survive. However, some animals seem to have remembered this ancient companionship, and have joined our lives. And other animals seem to somehow distantly recall this as well, though while the world retains its current settings, their wild nature will remain (ie the tragic stories of people who try to turn untamed animals into "pets".)

God mean certain ones to be companions to us, I am certain of this. And humanity is charged with stewardship of this world, which includes the animals. Those we welcome into our homes are just as much familly members, with the level of responsiblity accompanying. But we get so much more. I know without my cats, the trevails I have endured over the last several years would have been far more difficult.