Roscoe

Farewell to the dearest friend I'll ever have

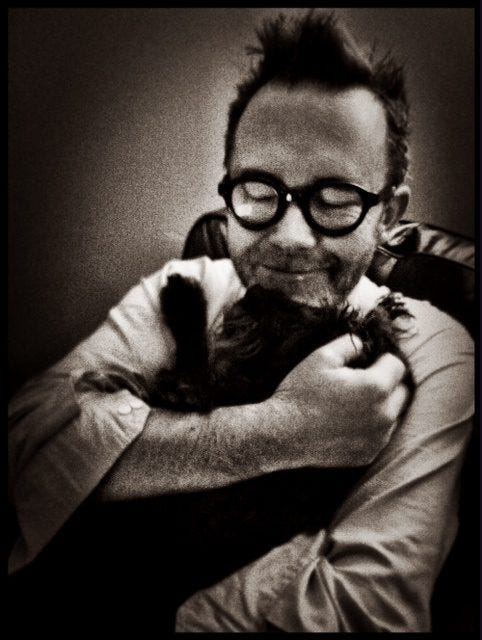

My little friend Roscoe is gone, or he will be by the time I reach the end of this letter. Julie messaged me earlier today to ask my consent to have him put down. He’s very old. Has been incontinent for the past two years. Is mostly blind, and deaf. He was so demented that he didn’t recognize me when he last saw me, in October. Look at him here, in his diaper, visiting Matthew and me in Matt’s apartment last fall. He doesn’t know who I am. I can see the tension in his body, because he’s not sure where he is.

Of course I said yes when Julie asked. I don’t want him to suffer. I knew when I told the old boy goodbye last fall that that would be the end. And now it has come.

I have thought for some time about what I would say when Roscoe left us, but I find now that I’m out of words. When Julie sent word later that the vet appointment was set for this afternoon, Baton Rouge time, I retired to my bedroom here in Budapest and fell to pieces in a way that only a man whose ancient dog faces death can. But I’m a writer, and the only way I could hold myself together was to get out of bed and write through the tears. So here I am.

When Roscoe found us back in 2007, I was not really a dog person. Julie and the kids were on the playground in Dallas one Friday. She phoned me and said that an older puppy had wandered up to them, a sweet little black dog, and he looked like he had been mistreated. Can we bring him home? Well, I said sternly, okay, if he’s been abused, but he goes to the pound on Monday.

He never went to the pound.

We named him Roscoe P. Coltrane, after the sheriff in The Dukes Of Hazzard. He chose me as his alpha, though it could have been anybody. On one of his first days in the house, he came into the kitchen and saw me with a broom, sweeping, and flipped out. We figured whoever owned him had beaten him with a broom. Still, he wanted me. He wanted me in spite of his fear and confusion. When I would sit on the couch, he would jump in my lap and sit there, still and trembling, trying to overcome his terror. I fell in love with him then. I could not understand why this dear little creature was afraid of me, but also loved me so much that he pushed through the fear to make a connection.

We took him for a walk around the neighborhood before we had him vaccinated. He sniffed some dog poo, I guess, because one Sunday morning before church, I found him behind the air compressor in the backyard, dying. I sent Julie and the kids to church, and took him to the 24-hour vet. The doctor told me that he had some disease, I forget what now, that unvaccinated dogs get from sniffing dog poo. He had a fifty percent chance of survival, the doc said, but even if he doesn’t make it, this is going to cost you $1,500.

I thought about it. I could have had Roscoe put down, and told Julie and the kids that there was nothing the doctors could do. They would never know. But I would know, and I could not be that guy. “Do your best,” I said. And they did. When Julie and the kids went to see Roscoe in the veterinary recovery the next day, they heard his tail thumping at the sound of their voices. That was the best $1,500 I ever spent.

The vet told us he was a “schnoodle” — half Schnauzer, half poodle — a breed that is good with kids. That Roscoe was. He adored our children. He went with us to Philadelphia, and became the terror of backyard squirrels. I remember turning him loose at the front door, and him turning into a black flash, rocketing around the back of the house to see if he could catch a squirrel. Never did.

Philly was the first time the Texas dog saw snow, and he loved it. When we left for Louisiana a year and a half later, old Rosky rode shotgun with me in the big truck, all the way home. He was sitting at my side when the truck rattled to a stop, and we were home.

I was so full of hope then. I had no idea what was coming next.

My life began to fall apart six months later, when I found out the truth about what my Louisiana family thought of me, and us, and with my subsequent Epstein-Barr diagnosis, and then with the start of my marriage’s collapse. This is when I learned the true value of my little dog’s love.

He had an uncanny way of sensing when one of us was in pain. He would come over to us, jump in our lap, and love on us. I love that Southern phrase: “to love on.” It implies active love. I don’t know if you could call lying like a lump in one’s lap active love, but I would hold him close, and it was like he absorbed all the pain in my heart. The pain I could not allow my children to see, Roscoe took it. Many a night, when I knew the kids were in bed, I would sit in the darkness of the living room, desolate, holding Roscoe close, and weep over the tragedy of it all. And I suspect my wife could say the same thing.

He was annoying. Barked at everything that moved through the yard, which became especially irritating as he aged, and began losing his sight. Any blur or shadow might be a squirrel, and he was having nothing of it. He ate chicken poo. Did doggy things. Peed on a houseguest’s leg. But we all rolled with it, because he was Roscoe, and he was the family’s heart.

We watched his hair turn from jet black and auburn to salt-and-pepper. He slowed down. He wasn’t as eager to play. Still … Roscoe! If anything, he became more dear as we realized that he wouldn’t be with us forever. He had the habit of curling up in my arms like a baby, and snoozing deeply.

You could tell he was really out when his mouth opened slightly.

I sometimes had a contemplative attitude towards Roscoe. He would be in my arms on an ordinary night, staring up at me with his chestnut-colored eyes, with the purest love. It was eerie; the kids noticed too. It was utter adoration. The feeling was mutual. There was nothing complicated about Roscoe’s love. In a family suffering a prolonged crisis that nobody could talk about but everybody sensed at some level, Roscoe was the still point in a disintegrating world. I would hold him, and watch him as he slept, and silently thank the Lord for sending him into my life. Into our lives. I needed him far, far more than he ever needed me. Knowing that this awful day was coming one day only made my love for him more intense.

But hey, at least I was able to use my influence in the publishing world to get his memoir published:

And soon he will have gone on to the next world. I wait here in Budapest for notification. If Roscoe is not waiting for me in heaven, I will have to have words with the Landlord. I cannot imagine perfect happiness without my sweet friend. My son Lucas is sending me photos of what Roscoe doesn’t know is his last afternoon on this earth. I just saw one of him lying in the sunshine in the back yard, warming himself. It sent me into convulsions of tears. How many afternoons did I watch my little friend stretched out on the grass, taking the sun’s rays, not a care in the world? He doesn’t know what is about to happen to him, that he is going to take leave of his family forever. I am secretly glad I don’t have to be there to oversee this. They all love him as much as I do, and would not be doing this if it could be put off even another day. They’re doing this because we all love him so much, and can’t bear to see him suffer.

Ah, life. It hurts so much. I have had so much taken from me in this past year, since April 15, when the e-mail arrived announcing that I would soon no longer have a wife. As I’ve stressed, as much as I hate divorce, Julie and I really had reached the end. There were about a thousand better ways to execute the damn thing, ways that could have spared all of us the shattering pain we’re going through now, but when even priests tell you it’s time, when there’s nothing left but pain, it’s time. Somehow, Roscoe’s necessary passing is a twist of the knife. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t blame anybody for this. If we were happily married, this day would still have come. But the fact that it has come under these circumstances makes it crushingly sad, beyond what I could have anticipated. If my dear firstborn son Matthew weren’t coming over next week, and if we didn’t have each other to look after, I would just as soon the vet give me a shot of what Roscoe is going to have, and I could fade to black with him.

This too shall pass. But the memory of this little dog, and what he meant to me, will be with me until I draw my last breath. He changed me. He made me a better man. Never before did I care much for dogs. Now I regard them as a sign that God loves us. Here we are below on the last time we saw each other. Once we were so close that he knew I was coming home long before my car drew near (Julie and the kids saw this happen many times). When we returned as a family after a month in Paris in 2012, he was ecstatic, and leaped into my arms (see the last photo below). But last fall, Roscoe was no Argos: by then, he was lost in the fog of old age, already having lived past the allotted time for his breed, and no longer recognized his master. I grieved this, but I dared not let the feeling take hold of me. Had to be brave. Besides, had I broken down on the front porch of what used to be my house, there would have been nobody to comfort me. That’s how all this has gone down.

He may have been gone already then, but on so many agonizing loveless nights over the past ten years, Roscoe was there for me, reminding me that there was at least one thing in this world I would never lose: my dog’s love. I think now about running my fingers through his floppy black curls, scratching him under his chin, hearing him groan with pleasure as he slept deeply in my arms, and I can only give thanks to God for the gift of this castaway, this stray, this dear little creature who needed a family, and not only got one, but made one.

The word has just arrived from Baton Rouge. He is gone. This hurts beyond all telling.

Goodbye, baby dog. May the good Lord shine a light on you. You were golden.

One of the finest tributes to man or dog I’ve ever read. And yes I fully agree that dogs are gifts from God.

I have no words. God bless little Roscoe! you never suspected there was a Roscoe-shaped hole in your heart.